The judgment of the Supreme Court in the Janhit Abhiyan case, which upheld the 103rd constitutional amendment providing reservation to the economically weaker sections, gives considerable importance to the doctrine of the ‘basic structure of the Constitution’. Although this verdict was primarily concerned with the validity of economic criterion for affirmative action policies, the judges took this opportunity to reflect on a few basic principles associated with the India-specific idea of a constitutional democracy.

This crucial judicial explanation of the ‘basic structure’ thesis is not merely about the operational aspects of our Constitution as a legal document. It is also inextricably linked to the core values, principles and ideals that are supposed to determine our political common sense. This is precisely the reason why we need to read this judgment in relation to the actualities of political processes and trajectories.

For the sake of analysis, it would be important to focus on this judgment in its entirety. It is true that the three judges, J.B. Pardiwala, Bela M. Trivedi and Dinesh Maheshwari, who gave the majority view, differed significantly from the opinions and reasoning offered by U. U. Lalit and S. Ravindra Bhat. However, the entire bench seemed to agree that the doctrine of the basic structure of the Constitution is a relevant and effective judicial tool. This fundamental agreement actually encourages us to evaluate three issues that are central to contemporary political imaginations in India: the centrality of the constitutional ideals in our public life; the possibilities of change in core values and their interpretations; and the limits of popular politics.

The Indian Constitution has always been an important source of politics in India. All political parties agree that the Constitution is the foundational document of India’s political existence. This overwhelming and enthusiastic acceptance of the Constitution, however, should not be seen as an end in itself. The judgment makes a very interesting comment in this regard. It says: “the framing of the Constitution… is a capital political fact and not a juridical act. No court or other authority in the State under the Constitution can, therefore, determine the primordial question whether the Constitution has been lawfully framed according to any standards. Even if a Constitution is framed under violence, rebellion or coercion, it stands outside the whole area of law, jurisprudence and justiciability. The basic principle of constitutional jurisprudence is that the Constitution is the supreme law of the land, even supreme above the law and itself governing all other laws.”

This observation underlines the relationship between the different streams of our national movement and the process of Constitution-making in the late 1940s as a crucial historical fact. The different, even conflicting, political values and ideals that were cherished by political leaders of that time became the basis of the discussions and deliberations in the Constituent Assembly. The final draft of the Indian Constitution was the outcome of this carefully worked out political consensus.

The Constitution, in this sense, primarily stands for the values and principles that were adopted to produce a set of laws and rules. Any attempt to create a dividing line between the principles of the Constitution and the provisions it makes for the effective functioning of the political system is clearly a violation of constitutional morality. This is exactly what the court says: “What constitutes basic structure is not like ‘a twinkling star up above the Constitution.’ It does not consist of any abstract ideals to be found outside the provisions of the Constitution. The Preamble no doubt enumerates great concepts embodying the ideological aspirations of the people but these concepts are particularised and their essential features delineated in the various provisions of the Constitution.”

This brings us to the second issue: the possibilities of having multiple interpretations of the core values and ideals. Evaluating the powers of Parliament, the judgment makes an important point. It notes: “… when it comes to the validity of a constitutional amendment, one has to examine the validity of such an amendment by asking the question as to whether such an amendment violates any overarching principle in the Constitution. What is overarching principle? Concepts like secularism, democracy, separation of powers… judicial review fall outside the scope of amendatory powers of the Parliament.” In a legal-technical sense, this comment is about the amending powers of the legislature. However, law-making is also a political act, which reflects the ideological orientations of the dominant political players inside Parliament. A complex and sophisticated legal-technical vocabulary is often used to hide the direct political purposes.

The Citizenship (Amendment) Act 2019 is a good example. The joint parliamentary committee report shows that the government justified this law on technical grounds inside Parliament. Concepts like secularism, minority rights and equality were used to make a legally acceptable argument. However, Bharatiya Janata Party leaders spoke a very different language during the election campaigns. The term, secularism, was described as an antithesis of Indian ethos, while minority rights were criticised for being a tool for politics of appeasement.

Of course, the core values of the Constitution, such as secularism, are subject to multiple interpretations. However, it does not mean that such values are only evoked strategically to fulfil certain legal-technical requirements. This is not a question of interpretation; rather it symbolises the moral and intellectual decline of the political class.

Finally, the basic structure thesis may also be used to underline the limits of populist majoritarian politics. The judgment makes a very crucial and far-sighted observation: “… the core principles of the Constitution are foundational — they are at the core of its existence… This is not to mark out the possibilities of structural adjustments in the foundations with time. The foundations may shift, fundamental values may assume a different meaning with time but they would still remain to be integral to the constitutional core of principles, the core on which the Constitution would be legitimately sustained.” It simply means that constitutional values and principles are to be observed as ‘reference points’ in the realm of actual political life. This self-imposed limitation is necessary to achieve what is described as ‘a transformative constitutionalism’ in this judgment.

The political class, on the other hand, is obsessed with the election-centric discourse of democracy. The idea of winnability is always overemphasised as if election is a political market place where parties have to bargain with voters. This tendency underlines a very specific form of political majoritarianism in the Indian context. The ideals of the Constitution, such as secularism, social justice and equality, are seen as ‘settled issues’ to create an impression that democracy is all about the rule of the majority.

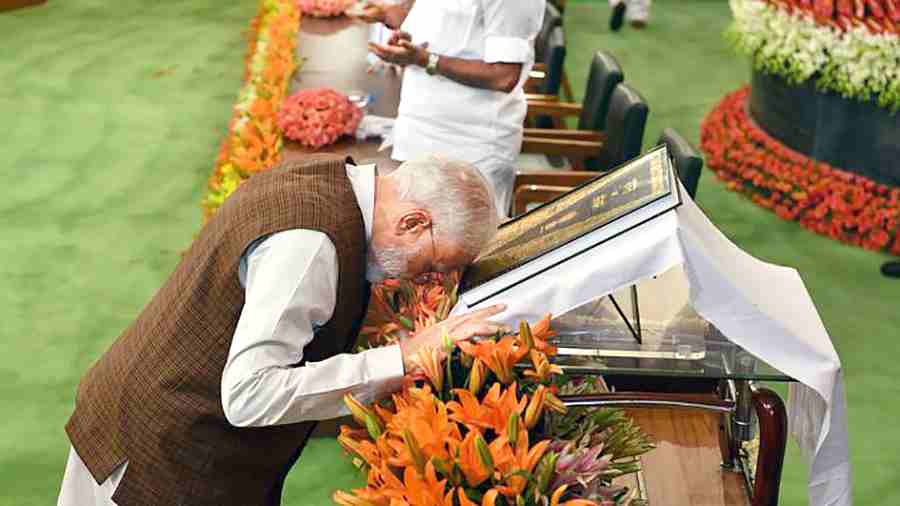

It is true that the Indian Constitution is recognised, respected and even worshiped by all political parties. Yet, there is a serious disengagement with the idea of constitutional democracy.

Hilal Ahmed is Associate Professor, CSDS, New Delhi