It’s a bleak irony that the play, Death of a Salesman, is a modern American classic whereas the film, Ek Doctor Ki Maut, is a classic of modern Hindi cinema. Death is real in Arthur Miller’s play while it is a metaphor for exclusion and ostracism in Tapan Sinha’s film based on the story by Ramapada Chowdhury. Those who know both the play and the film may recognise the irony that a nation of science, invention, and industry projects the waning days of a dejected travelling salesman, while a developing nation of rusty postcolonial bureaucracy stages the stifling of scientific ambition by corruption and red tape. What they have in common is obvious — a focus on the profession. And death, as metaphor and reality.

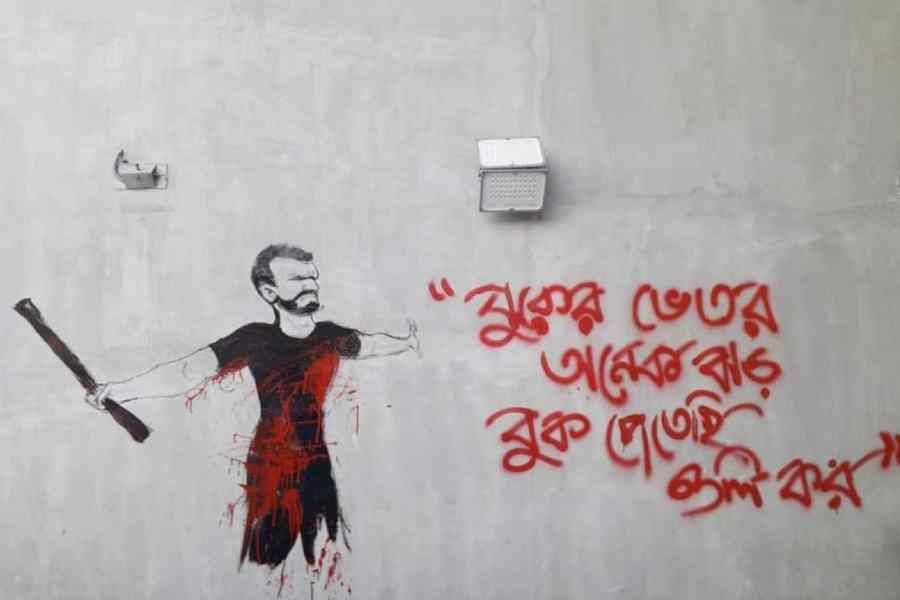

For the educated youth from the lower-middle and working class of this subcontinent, the price of a profession feels exorbitant today. Sometimes the very right of entry to a profession appears unattainable. Just as challenging is the very possibility of survival there without power and connection. “Why was Abu Sayed shot dead in cold blood?” asks the headline of an article in Dhaka’s The Daily Star, about one of the earliest casualties in the government crackdown on the student protests. It was the viral video of Sayed’s killing that propelled Bangladesh’s recent youth rebellion like wildfire. Who was Abu Sayed? He was one of the nine children of very poor parents — the report calls him “the youngest and the brightest” of them. His family was elated when Sayed got into Begum Rokeya University and became the very first member of the family to attend college. All his siblings pitched in funds to help him, even drawing money from the savings for their own education. It was everyone’s hope that Sayed would change the quality of their lives after joining government service. And that was where Sayed met the final impediment. Thanks to the then government’s quota policy, the likelihood of his getting a government job was bleak, no matter how educated or qualified he was. A natural interest in quota reforms made him a part of the protests. The result was the death of a student, standing with his arms stretched out, unarmed except for a stick, no threat to anyone, easily 50-60 feet away from the police. His death started something far larger than what he or his family could have ever imagined.

A young doctor came from a lower-middle-class family in Sodepur in the northern suburbs of Calcutta. Her mother is a homemaker, and her father runs a modest tailoring shop. “We are a poor family and we raised her with a lot of hardship” — her 67-year-old father told The Times of India. Every reader of this newspaper knows what happened to this 31-year-old trainee doctor who, for her postgraduate training, chose R.G. Kar Medical College and Hospital, an hour’s bus ride from her home in Sodepur. A consistently high-performing student through her board examinations, she qualified through both JEE and Medical. Did she even have the means to pay the exorbitant bribes that we hear have become the norm to pass through the loops of training and qualification? We don’t know if the ongoing trial will reveal her ethical position before this corruption, which, from what we’ve heard so far, was stubbornly resistant. But either way, her background offers little evidence that she was even capable of arranging for the absurd price demanded just to enter her profession.

A good, hardworking student who actually cleared the required examinations. Something that feels like an anomaly in the age of doctored and bribed admissions, in the wake of the scandalous fiasco over the question paper leaks in the National Eligibility cum Entrance Test for medical degree programmes. What was an inevitable meeting of ill-fated forces — the sheer desperation for a seat, greed in local administration, and a giant, creaky, unstable system perpetually waiting for disaster — still remains an ill-resolved controversy. That is as hard to believe as it is ominous for the millions of youth who take these tests in the hope of a place in the medical profession that, at least in Bengal, now lies deeply stained.

The impediments grow heavier in the path of the serious, well-meaning, educated youth who have followed every rule in the book to higher education and professional service. Coming from poor and working-class backgrounds in the provinces and hinterlands, they are capable of heralding their families’ entry into the middle class. More often than not, their goal is to work in the government sector. And this is where the greatest dereliction of responsibility has taken place across much of this subcontinent. Just about a month ago, three young people — two women and a man — drowned in a private coaching centre for UPSC examinations in Delhi’s Rajinder Nagar. As one survivor said, in spite of charging a fee of two lakh rupees, the coaching centres had no safety standards in spaces where the youth studied and spent time. Moving through terrible conditions and mental health challenges in Kota and Rajinder Nagar, our aspiring youth fall off the grid in countless visible and invisible ways.

Their loss is the tragedy for which their families will never find solace or closure. But the collective pattern of obstacles in higher education and professionalisation trajectories of poor, provincial and struggling youth is a colossal tragedy across our subcontinent. We have here what is dying in the post-industrial nations — a population dividend, auguring a new and expanding educated workforce. We’ll never know if Abu Sayed might have been a more efficient civil servant, or the postgraduate trainee-doctor from Sodepur a more empathetic healer than the usual entrants from the privileged strata. But it is evident that they hold the only possibility for a larger professional class the Indian subcontinent desperately needs as public sector infrastructure and human resources come crumbling down everywhere. But these are exactly the people who are grossly under-employed, exploited, and misled, never mind how much they play by the book. The price of the professions, in the end, is absurd not only for them, but for their communities, states, and nations on the whole.

Saikat Majumdar is Professor of English and Creative Writing at Ashoka University. Views expressed are personal