Between two ordinary people, the hug is always simultaneously an attack and an invitation. The attack part is both parties saying, ‘I am moving forward to embrace you fully,’ and the invitation part, again mutual, is both saying, ‘I invite you to embrace me fully.’ In the old days, the hug was the ultimate gesture of complete trust because either person could stab the other in the back while holding them tight.

Between leaders of nations or others in high office, the hug takes on an added significance. World leaders usually shake hands, sometimes preceded by a hand pressed to the heart or a namaste. The hug is normally used sparingly, to indicate great warmth, familiarity and special friendship between two leaders and, by extension, their respective nations. Since the advent of newspapers and photography, and carrying over into televised times, the first greetings between leaders have been mindfully and carefully used to create an image for wider dissemination. Handshakes, single-handed, double-gripped, with one person gripping the other on the arm or above the elbow, the length and warmth of contact, have all been analysed with the forensic, slow-motion attention usually devoted to a tennis player’s or a golfer’s grip.

For instance, among the many ways the presidency of Donald Trump has been mapped is through a series of clips of his handshakes and hug-exchanges with other world leaders: the intimate holding of Theresa May’s arm, the little arm-wrestle between Trump and Putin, the schoolboy yank Trump would deploy to pull other leaders to himself, Macron’s and Trudeau’s varied counters to that, Angela Merkel recoiling from an attempted embrace, and so on. Before Trump, you had the admiration for the grace and style of Barack Obama’s comportment during summits. Well before that, you had Fidel Castro and the Soviet president, Nikita Khrushchev, hugging to show socialist solidarity and, then, you had the antagonistic ‘Kitchen Debate’ between Khrushchev and the then vice-president, Richard Nixon, with photographs of Nixon actually tapping Khrushchev on the chest with a pointed finger.

The image created by two leaders shaking hands or hugging is usually deliberately intended to serve the political purposes of both leaders. Sometimes the image is created through mutual co-operation, sometimes not. Khrushchev’s successor, Leonid Brezhnev, for example, liked to plant a socialist kiss on the leaders he met, not excluding the unhappy-looking US president, Jimmy Carter, who Brezhnev ambushed with a kiss while shaking hands on a major missile-reduction accord. As with Trump’s handshakes and hugs, there is a whole series of photos of Brezhnev kissing or attempting to kiss various world leaders; the ones who were under his thumb in the Warsaw Pact knew better than to do anything other than enthusiastically kiss back, complete with hand on the back of the neck.

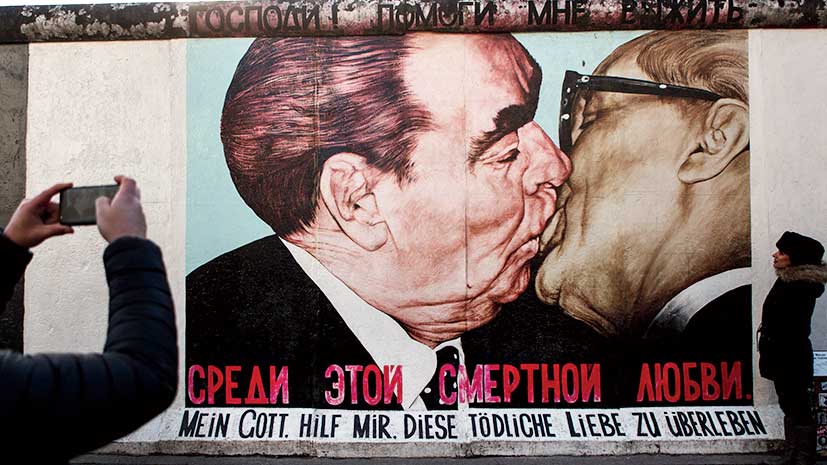

Brezhnev was not to know it, but one of his kisses backfired spectacularly down the time. There is a famous photograph of Brezhnev kissing communist East Germany’s boss, Erich Honecker (picture). So enthusiastic are both men in expressing their International Socialist Solidarity that at first glance it looks as though they are kissing mouth to mouth, rather than each other’s cheeks. About a decade after the picture was taken, the Berlin Wall fell and the Soviet empire collapsed. An artist called Dmitri Vrubel painted a large reproduction of the Brezhnev-Honecker photo on the side of the newly breached wall with the title, My God, Help Me to Survive This Deadly Love. The satire and the disgust towards the two widely-hated despots were very clear in the painting as well as in the title. Brezhnev was already dead but the disgraced and ejected Honecker lived to see the photos of the painting spread across the world as a celebratory marker symbolizing the end of a particular cluster of tyrannies.

There must be a tremendous adrenalin rush you experience if you’re a leader of a big country attending a world summit. In that surge of body chemicals, you would be aware that you need to make an impression not only with your counterparts but also with the all-important media. You would be aware of the contradictory pull of grace and dignity on one hand and the urge to create an impression on the other. If you had a good understanding of world affairs, if you knew your stuff about the issues at hand, if you knew you were already respected as a leader by others, then you’d be securely confident that your impact would be felt in one-on-one conversations, in negotiations, in the speech you would give to the summit. If, on the other hand, you were a self-obsessed know-nothing, with only a shallow grasp of the matters at hand, a bit befuddled about social dynamics when confronted with powerful men and women from other cultures, then, like Donald Trump or some dictator of a banana republic, you might bumble about trying to hug people who didn’t particularly want to hug you. You may reach for close contact with strangers in the middle of an unprecedented epidemic requiring physical distancing between the most amicable of friends. You may then help create images that turn you into an immediate laughing stock in international media, images that could, further down in history, give another meaning to the phrase ‘my god, help me survive this deadly love’.