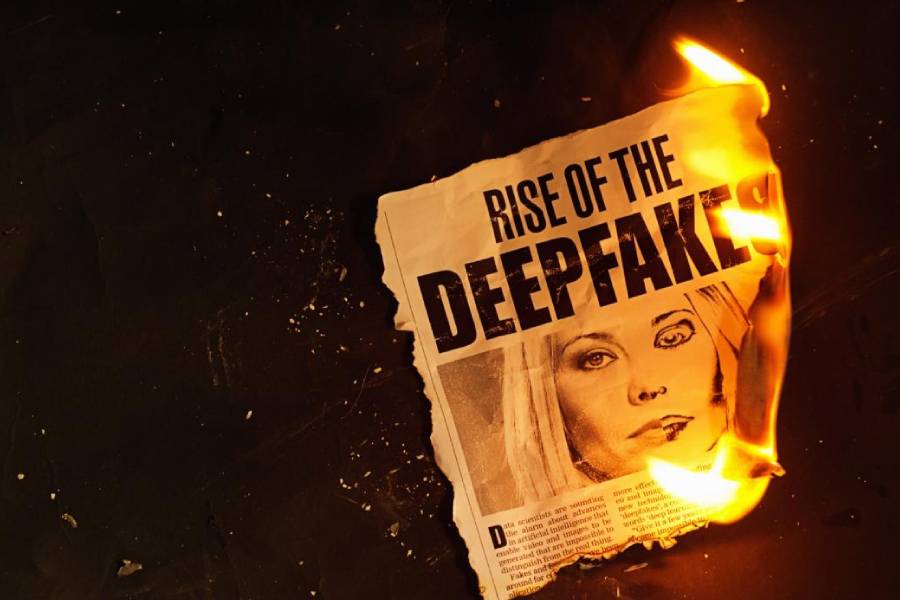

Art often attempts to imitate reality. The endeavour is usually benign. But modern technology’s projects of imitation are turning out to be far more sinister. The rising concern with deepfakes is a case in point. Deepfakes are images and videos of real people that are created by using a form of Artificial Intelligence called ‘deep learning’. Two Indian actresses, Rashmika Mandanna and Katrina Kaif, were targeted by deepfake technology recently and their morphed, objectionable videos disseminated for consumption. Interestingly, the transgressions took place even as nations around the world met in Britain and signed a global pact against the risks posed by ‘frontier AI’ — highly capable, generative AI models that pose severe risks to public safety.

India, one of the signatories to the pact, has been a witness to deepfake’s sinister powers for a while. Last year, a deepfake photograph was created to erroneously depict wrestlers protesting against the chief of the Wrestling Federation of India posing for a selfie inside a police van. In July this year, a man in Kerala was robbed of Rs 40,000 in a deepfake scam. It has taken the targeting of two celebrities for people to wake up to the threat. But the threat, data suggest, has been worsening. Researchers have observed a 230% increase in deepfake usage by cybercriminals and scammers and have predicted that the technology would replace phishing in a couple of years.

The State seems to have been jolted to action too. Earlier this week, the Indian government declared deepfakes to be a violation under the IT Rules 2021. Any company that does not take down content flagged as deepfake within 24-36 hours would be liable to prosecution under Indian laws. India’s regulatory approach is being echoed around the world. The European Union has issued guidelines to set up an independent network of fact-checkers to help analyse the sources and the processes of deepfake content creation. China’s guidelines direct service providers and users to ensure that any doctored content using deepfake technology is explicitly labelled and can be traced back to its source. The United States of America has also introduced the bipartisan Deepfake Task Force Act to counter the menace. Regulation is necessary to check the creation of spurious content and identity theft using deepfakes. But care should be taken to ensure that the beneficial potentials of AI technology remain unaffected by policy enthusiasm for regulation.

The most obvious challenge for regulatory technology would be to identify deepfakes. But there is a graver threat lurking around the corner. At a time when the refinement and the weaponisation of technology are increasingly making it difficult to differentiate the real from the artificial, the concept of deepfakes is also being invoked to make the real appear fake. For instance, in 2019, the army in Gabon launched and won a coup against an elected government on the suspicion that a video of the then president was a deepfake even though subsequent forensic analysis did not find traces of alteration or manipulation. All this points to the unfolding of a deeper — existential — crisis in which human society, at the mercy of technology, is losing its ability to separate the real from the uncanny. This will have profoundly destabilising implications on the future of the species.