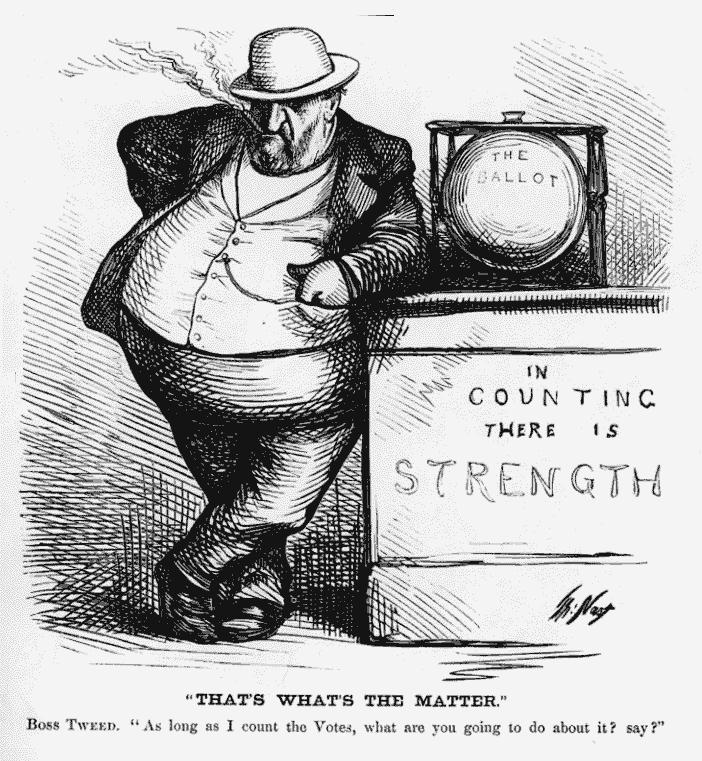

India is a representative democracy whose citizens are vested with the power to elect their legislatures through universal adult franchise. Can it be said that Indian democracy is marred by ‘Tweedism’? The concept of ‘Tweedism’ is attributed to the American politician, William M. Tweed, who consolidated his position in Tammany Hall, the seat of New York City’s Democratic Party, and by 1860 controlled all Democratic Party nominations. ‘Boss Tweed’ is said to have quipped, “I don’t care who does the electing as long as I get to do the nominating.” Tweedism can be understood by viewing a corrupt, skewed democracy in which one group is in control of decision-making to fulfil rent-seeking behaviour. ‘Tweedies’ are individuals or a group of individuals — business and political elite — who influence the nominations process. The phenomenon refers to the funding of candidates by the same group of economic elite that intends to contest elections. Tweedism may be relevant to the presidential system of politics in the United States of America. But it can be extrapolated to get a fairer picture of the Indian parliamentary system.

The manner in which Tweedies operate in the Indian context can be comprehended by examining the funding of political campaigns which, in turn, makes India a flawed democracy. Political parties either secure maximum funding or surreptitiously favour the business or political elite. The nomination of the favoured candidate acts as a filter that lands a blow on the representative nature of democracy. This first stage of nomination is followed by what can be called as the second stage where the real ‘election’ takes place. The problem with such a process is that the majority of citizens are ousted from the first critical step because the nomination of the candidate is done by the economic and political elite. Consequentially, democracy is made more responsive to the funders — Tweedies — than to citizens even though it may appear that every citizen possesses an equal right in deciding the suitability of the candidate for representation.

Deep pockets

What is being witnessed in India today serves as a perfect example of Tweedism wherein public policies are being tweaked to favour the business and political elite. This transgression is caused by the conditional nature of political funding. This precisely is the reason why major political parties, including the Bharatiya Janata Party, refuses to come under the scanner of the Election Commission in order to put a cap on the sources of funding.

Can Tweedism then explain the following developments in the Indian political system? The non-existent Jio Institute has been recognized as an institution of eminence by the ministry of human resource development, even though the finance ministry expressed reservations about this. There is also the alleged creation of Reliance Defence prior to the Rafale deal between India and France. Can these incidents explain the root cause of a democracy’s acquiescence to the elite? It can be argued that this kind of corruption can cleverly bypass the institution of representative democracy and its principles. The ones who are at the receiving end are the citizens who have, over the years, failed to exercise their agency in the form of adult franchise in its truest sense.

The ideals of an inclusive democracy can be reclaimed in the following manner. First, political parties must be allowed to contest elections with the help of funding by citizens. Second, there has to be a logical upper limit on campaign expenditure as was argued in the 255th report of the Law Commission on electoral reforms. Lowering the cap for funding creates a window for illicit financing. Lastly, all funding initiatives must be operated under the aegis of the EC and the details must be made public. Citizens may not be sagacious enough to operationalize the Citizen Fund. A sensitization campaign can help solve this problem.