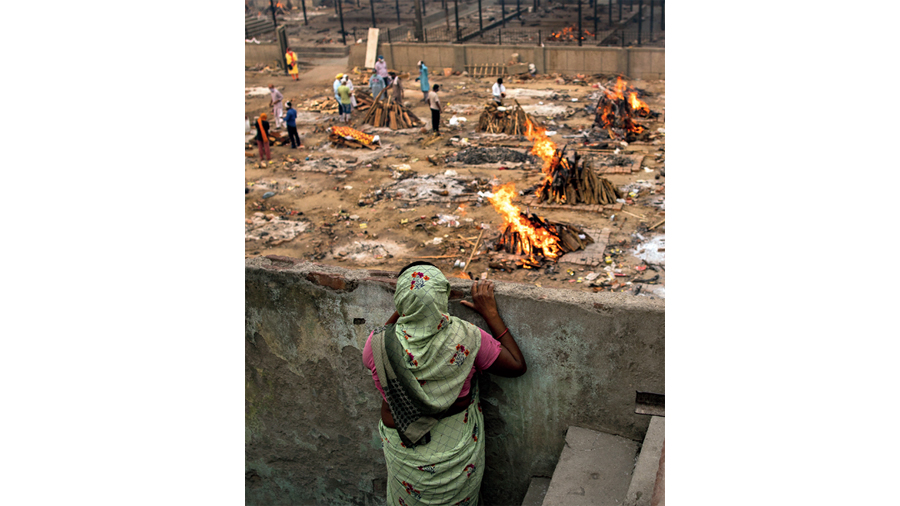

Much before India’s health infrastructure and economy could even begin to recover, the second wave of Covid-19 came like a tsunami, exposing a callous, unprepared government that put the lives of millions of citizens at risk. It was only in January this year that the prime minister had claimed that India was one of the world’s first nations to be victorious against Covid. The nation was showcased as the pharmacy of the world with its indigenous vaccine as well as having the world’s largest capacity for producing them. Within three quick months, India’s fragile healthcare system has now been fully stretched with an alarming shortage in beds, medical equipment, oxygen, medications, vaccines and even space for cremating the dead. In a surreal run of events, when all this was happening, the prime minister devoted his energy in addressing overcrowded election rallies in which Covid protocols were completely ignored. After the elections, he moved his attention to building a new Parliament complex with a project cost of Rs 200 billion, which was declared as an essential service at a time when the stench of death was reeking across New Delhi. Internationally, India has now been reduced to a basket case.

My purpose is not to go into the details of this human tragedy, a large part of which was created by the government’s apathy and cruelty. There is another — equally tragic — calamity being played out. The economy of the nation is in a mess. Last year, India witnessed a technical recession when its GDP fell by 23.9 per cent and 7.5 per cent, respectively, in the first two quarters of FY21. The third quarter showed a small positive growth rate of 0.4 per cent. India’s GDP was estimated to shrink by 8 per cent in FY21. However, the temporary abatement of Covid and the arrogant announcements by the government led most analysts to believe that India would recover to a growth of anywhere between 10-12 per cent in FY22. That has become impossible now. Organizations like the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank have begun to scale down their projections for FY22, as have major brokerage houses.

Aggregate growth rates are confusing numbers to most people. They hardly make any impact on a person who has lost his business or job or is faced with a sudden loss of income. According to the CMIE, from January 2021 to April 2021, 9.9 million people had lost their jobs, with April 2021 alone registering 7.3 million of the total. According to another study by the Pew Research Centre, 2020 witnessed a massive 32 million people slip from being in the middle class (in terms of income) to the lower income group. At the same time, the number of people living in India with an income of $2 or less per day increased by 75 million. This happened in a country where, according to another study done by Oxfam, the top 1 per cent of India’s rich held wealth that was four times of that held by the poorest 70 per cent, which amounts to approximately 950 million people. This has been referred to as the inequality virus.

The manufacturing sector is shrinking and the services sector is just holding on. Agriculture has been the saviour as far as growth was concerned in FY21. This year, with the farmer’s agitation lingering on and a completely heartless government refusing to yield, the productivity of agriculture is likely to be adversely affected even if the monsoons are normal. Food inflation is already on the rise, having climbed to 4.9 per cent in March 2021, and overall consumer inflation is approximately at 5.5 per cent. This worry about inflation will keep the Reserve Bank of India from going for aggressive interest rate cuts to boost productive credit and output. The banking sector is also under stress. The various steps taken by the RBI last year, including the moratorium on loan repayment, have left many banks with a larger level of non-performing assets. These will weaken the balance sheets of banks and make them hesitant to lend to businesses that are already hit by the pandemic.

On the employment front, business will be wary of hiring new people because there is no assurance of demand picking up in the foreseeable future and even if they were to employ more workers, they are not sure about how soon another round of disruption will come. There are some sectors where there is a seeming shortage of workers — paramedics, medical staff, nurses and doctors. However, adequate supply would require a few years for freshly qualified members to enter the labour force after acquiring proper education and training. It might be noted in this context that higher education is one sector where there has been quite a bit of disruption. Overall, a low and uncertain demand for output dampens the demand for credit and the derived demand for employment.

Another casualty of the pandemic’s effects and the indifference of the government is the natural environment. The government has put environmental safety and sustainability on a low priority. A glaring instance is the construction of the Central Vista in New Delhi that has resulted in the felling of hundreds of trees. Little wonder then that an international ranking of countries for environmental performance puts India at 177 out of 180 countries listed.

The government was ill-prepared not only for the second wave of Covid but also the second round of economic disruptions that would be caused by the second wave. In their policy stimulus for economic recovery, almost all nations boosted demand and ensured supply bottlenecks were eased. In India, the government took the opposite action: the supply side was given priority through enhanced credit flows to ease production and employment with little effort to boost demand. As a result, the recovery that was much touted as a V-shaped one is non-existent. The reality of what is happening in the economy is that there is a large pool of unemployed people emerging with no hope of new livelihood opportunities coming up. Even now, the government is curiously reticent about what it wishes to do to ensure that the economy does not slide into another technical recession.

A humanitarian crisis of stunning proportion and the weakened economy crippled by inadequate attention and faulty policies have put an overwhelming majority of Indians in a bind: they have to fight for their lives without the assured aid of modern science and medicine, and even if they survive, they will be poor and unemployed. A few people will be safe and happy. Big corporates have everything to gain if they acquire the right businesses.

There is a third wave that will arrive inevitably. Neither the economy nor the health infrastructure is in any state of preparedness. The government is singularly hesitant to act in a decisive manner. Economic recovery will be slow and patchy. India has lost a substantial part of the development it made during the past 20 years. India’s image in the international community of nations has touched rock bottom. India’s misery of death and deprivation has reached a level never experienced since Independence. While all this is happening, the prime minister of the nation is silent and invisible. One hears that in this moment of crisis a new residence is being built for him. This can only be described as abysmal stupidity at best and terrible cruelty at worst.