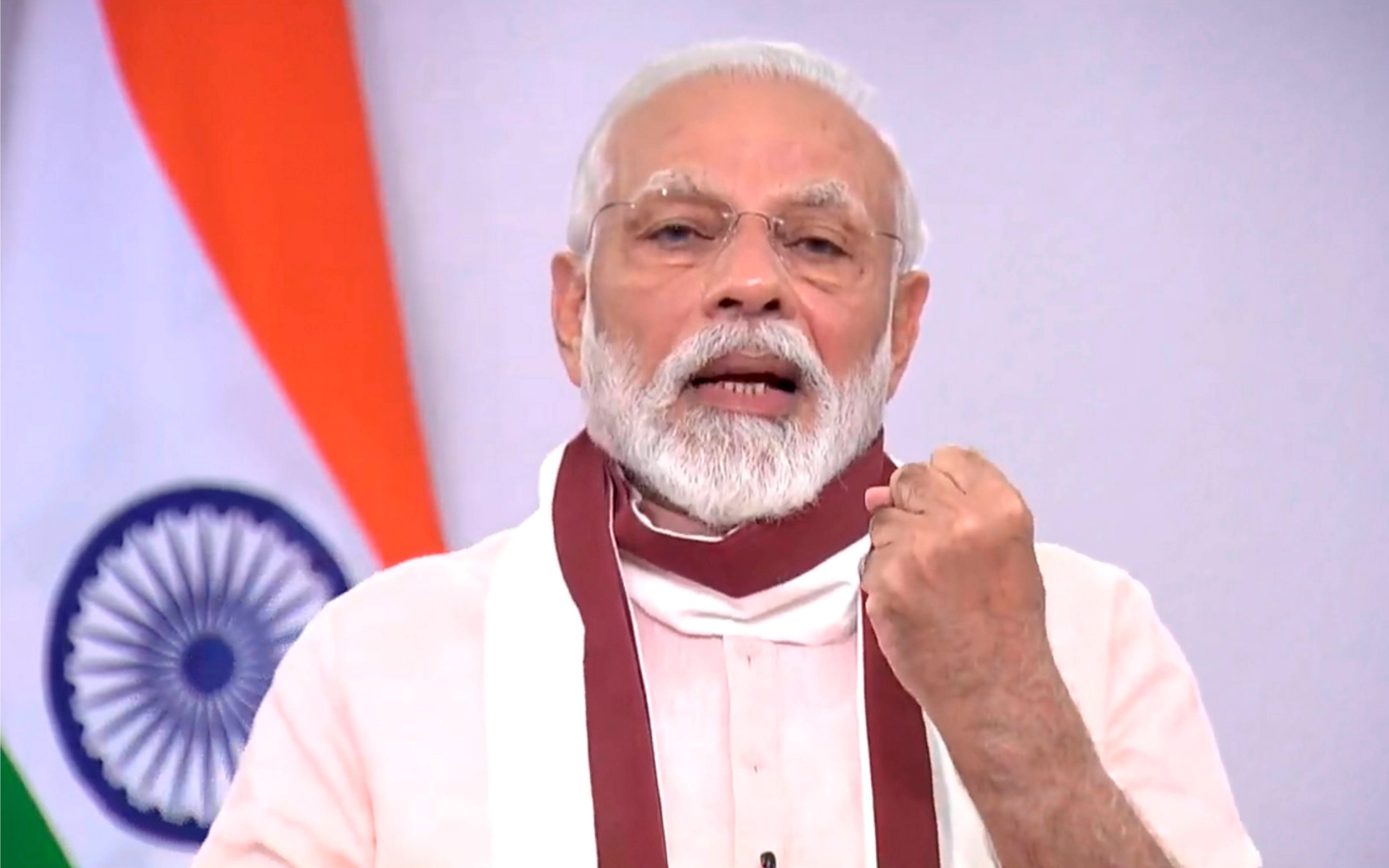

A warped doctrine of self-reliance, a roundabout way of reinventing the worst elements of the licensing raj system and a stab at corporatizing farm trade are the three bad ideas embedded in the Narendra Modi government’s ‘pretend’ stimulus plan to revive an economy that many believe stands on the brink of recession. The package, unveiled in a flurry of announcements over three days, does not display a resolve to deal with the horrific exodus of migrant labour across the nation through an immediate transfer of cash. Instead, it has chosen to focus on measures wound around undefined timelines while trying to rekindle belief among the walking dead in a glorious, kaamyaab Bharat of tomorrow. The farce disintegrates into tragedy on examining the bad elements in the package. Self-reliance was the mantra of Nehruvian socialism that led to the creation of the so-called “temples” of modern India — the public sector. Mr Modi resurrects the big idea but thinks small: aatmanirbhar Bharat will sprout a multitude of small and medium enterprises drawing on an imaginary Rs 3 trillion pipeline of automatic, collateral-free loans. This will not be backstopped by a government credit guarantee. Bankers — already loath to lend to borrowers with poor credit histories — are not going to suddenly find the nerve to create another trove of bad loans unless ordered.

Mr Modi’s ‘Make in India’ slogan, which was fashioned in his first term, lies in tatters; he is hoping that the new rubric of aatmanirbhar Bharat will resonate better in his second innings. He must keep these newly-created businesses afloat. That is why he has decided to reserve a slice of government contracts for micro, small and medium enterprises. The Centre has barred global tendering of contracts for procurement of goods and services above Rs 2 billion. In a perverse way, he resurrects the licensing raj concept of reservation for the small sector, introduced for the first time in 1967 and given statutory status in January 1984 when it was formally embedded in the much-reviled Industrial (Development and Regulation) Act of 1951. That system of reservation was abandoned after liberalization when the small-scale sector was asked to face global competition. The World Trade Organization estimates that government procurement amounts to about 25 per cent of gross domestic product in most countries. The redefinition of MSMEs — by raising capital investment limits and introducing a turnover criterion for the first time — places a protective umbrella over a wide swathe of industry.

The most sinister element is the decision to smash the hegemony of the mandi system in the pursuit of the noble goal of creating a national agriculture market. It also flirts with the idea of expansive contract farming. The moneybags in the corporate sector, who are looking to build their own e-commerce platforms, now have the opportunity to skirt the mandis and negotiate deals directly with the farmers. The government believes this will improve price discovery; it will not. Farmers with perishable goods on their farms will hardly be able to negotiate from a position of strength. The three tranches of the stimulus plan commit funding of up to a little over Rs 10 trillion. But there is only a driblet coming from the government. It is happy to shove those irksome liabilities on to the financial system and the monetary authorities.