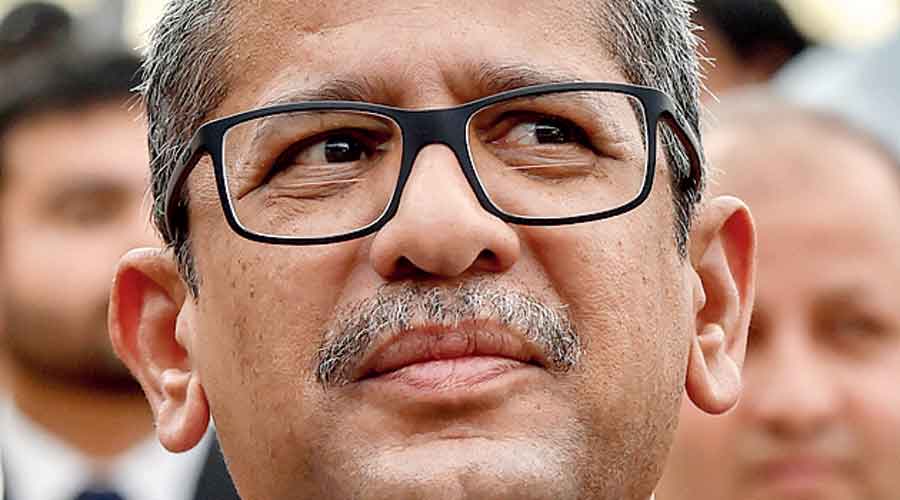

Mediation in disputes before going to court is not entirely new in India. Speaking at the India-Singapore Mediation Summit, the chief justice of India, N.V. Ramana, referred to a number of laws relating to commerce, industry and real estate that have provisions for compulsory pretrial mediation. The CJI expressed the need for a parliamentary enactment, an ‘omnibus’ law, to make mediation mandatory before a case comes to court. Mediation or conciliation and arbitration through an alternative dispute resolution system would not only lessen the pressure on courts but would also help citizens by reducing expense and time. Also, it would allow them to participate as ‘insiders’ with some control over the outcome of the process. The CJI reportedly saw ADR or mediation as a tool of social justice because it could provide ‘solace’ to litigants from the ‘middle or poorer’ sections of society. Alluding to the success of the ADR facility in Telangana and of Lok Adalats, the CJI felt that India should go into mission mode to ensure pretrial mediation before trial. The omnibus law is needed to ensure its legitimacy and enforcement.

There can be no doubt about the importance of mediation as the CJI seems to envision it. The ideal, however, may not always inform the real. The CJI reportedly referred to India’s tradition of mediation — the archetypal mediator being Krishna — conducted by chieftains or elders of the community, or merchant bodies in the case of merchants before the establishment of the ‘adversarial’ legal system of the British. But the tradition has continued in perverse — and illegitimate — ways, through khap panchayats and local shalishi bodies. Dominant interests of gender, caste, community and wealth are alive and kicking in their ‘decisions’, making nonsense of social justice ideals. Clearly, it is not just what the CJI calls ‘luxurious litigation’ by richer parties with vested interests which frustrate justice. Therefore, any provision for mandatory mediation will have to be enacted with especial care. Community bodies such as panchayats ‘mediate’ — they are not supposed to — in complaints of rape, for example. Surely the law on mandatory mediation would include only civil disputes? The enactment of such a law must define its limits precisely and ensure that gender, caste, religious and other biases that afflict Indian society are eliminated from the process.