On August 10, Joe Biden, the president of the United States of America, described China as a “ticking time bomb”, alluding to ongoing economic challenges. The US-China relationship is, arguably, the most consequential bilateral engagement in terms of wider economic stakes as China is one of the top foreign policy issues to have preoccupied the Biden administration.

In his 2020 article in Foreign Affairs, Biden had written that “China can’t afford to ignore more than half the global economy. That gives us substantial leverage to shape the rules of the road on everything from the environment to labor, trade, technology and transparency, so they continue to reflect democratic interests and values.” Both economies account for at least 40% of the global gross domestic product — China accounts for 17.2% and the US for 25%. For countries in the Global South like India, which has direct stakes in economic engagement with both countries, special attention needs to be paid to the granular changes that the US-China relationship is undergoing. Equally important is the need to understand the structural reasons that are underpinning these changes.

The Biden administration has been emphasising ‘de-risking’ rather than ‘de-coupling’ from China’s economy as its mantra. The US policy elite has been insistent that it wants to ensure that supply lines are resilient for all scenarios and that US technology meant for potential military use by China is guarded. The US is also keen that a portion of the blue-collar industrial jobs return to America. The two aspects are not totally mutually exclusive. The national security adviser, Jake Sullivan, had said in a widely-reported remark on April 27, 2023, that the US wants to minimise the transfer of technology that could potentially be militarily used in China and stated that “we are protecting our foundational technologies with a small yard and high fence.” Linked to this, on August 9, the US Department of the Treasury passed an executive order imposing restrictions on American investments in the Chinese technology sector, citing the risk that those investments could be used to help Beijing’s military and surveillance programmes. The US had already expanded sanctions against Chinese companies and organisations because of national security and human rights concerns, placing 721 Chinese companies, organisations and people on an ‘entity list’. China has responded with enhanced raids on US investment consultancy firms under its counterespionage law.

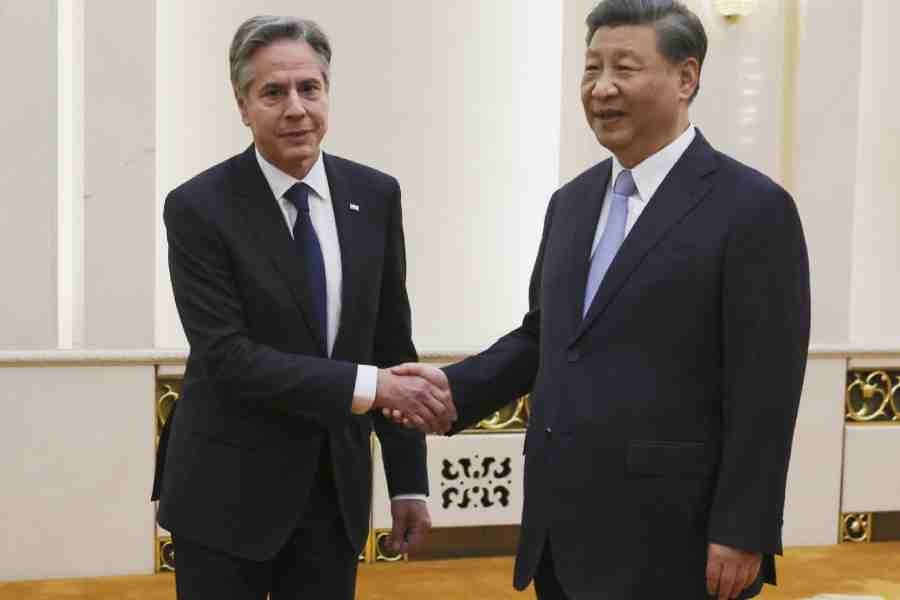

At the same time, the US has avoided an all-out confrontation considering China’s current manufacturing heft, as no other country at the moment, including the most populous, India, is ready with the relevant human resource and physical infrastructure. As The Economist mentioned recently, “having produced just a tenth as much as America in 1980, China’s economy is now about three-quarters the size.” China is America’s third-largest trading partner, after Canada and Mexico, with trade of over $700 billion every year. With each move to guard sensitive technology, which has irked the Chinese State, a senior US minister has descended on Beijing to smoothen the tempers between the two sides. In July, the US treasury secretary, Janet Yellen, visited Beijing; this was preceded by a visit by the secretary of state, Anthony Blinken, in June, who was accorded an audience with the Chinese president, Xi Jinping. The commerce secretary, Gina Raimondo, was in Beijing in August, which was preceded by the removal of export controls for 27 Chinese companies.

The developments come in the context of a slowdown of the State-propelled and controlled Chinese economy. All metrics reflect that. Youth unemployment reportedly hit a record high of 21.3% in June. Reports say the slowdown is hitting everything from commodities to the property market. American imports from China have fallen dramatically. What explains the slowdown is unclear due to the opaqueness of the Chinese economy. The pragmatic approach and low profile that marked the Chinese growth story for the last four decades had been jettisoned in favour of projecting China’s geopolitical power. China’s present economic and military prowess, with a per capita GDP of $12,720 and a defence budget of $224.8 billion, is seen as an instrument to achieve that.

As the 2024 US presidential elections approach, smart economics and domestic political compulsions will not necessarily be in tandem in the US. The narrative of bringing back manufacturing jobs to America, even though some of the jobs are redundant due to automation, is common to both parties; their tone and tenor, however, are widely different. China’s growth as the factory of the world, with its relatively cheap labour, initiated the process of the shifting of labour-intensive jobs from the US to China and, later on, to Southeast Asian countries. This severely impacted the political landscape of the US Midwest as blue-collar jobs either shifted or wages declined. Biden desperately wants to hold on to the narrow edge over the former president, Donald Trump, in some of the key swing states, which includes the traditional support of trade unions and blue-collar voters for the Democratic Party. The 2016 defeat of Hillary Clinton was attributed to the Democratic Party being unable to retain this traditional vote bank.

China’s industrial policies of the last four decades, and its entry into the World Trade Organization on December 11, 2001, which was facilitated in a large part by the Bill Clinton administration, catapulted the country into the league of great powers. American consumers and companies are enmeshed in China’s growth story. There is a de facto, inadvertent bipartisan consensus on the need to reset the four-decade US-China economic engagement. As the nuts and bolts of the reset become visible, the alacrity and dexterity with which the developing world responds, by granularly understanding the context and knowing its own limitations, will either make it a rare opportunity to capitalise on or a challenge to overcome.

Luv Puri is the author of Across the LoC