The Supreme Court, in its order on October 23, restricted the use of fireworks during all festivals across the country to a window between 8 pm and 10 pm. Delhi’s well-heeled gentry hailed the order in the hope that the city — which bears the brunt of pollution each winter — will have a cleaner Diwali this year.

But two weeks before Diwali, and a few hours after the apex court order, the air turned foul in the heart of the capital’s elite Lutyens’ zone. It reeked of menace and intrigue. The explosion took place well after midnight, quietly and stealthily. But its reverberations spread far and wide; its repercussions are still unraveling.

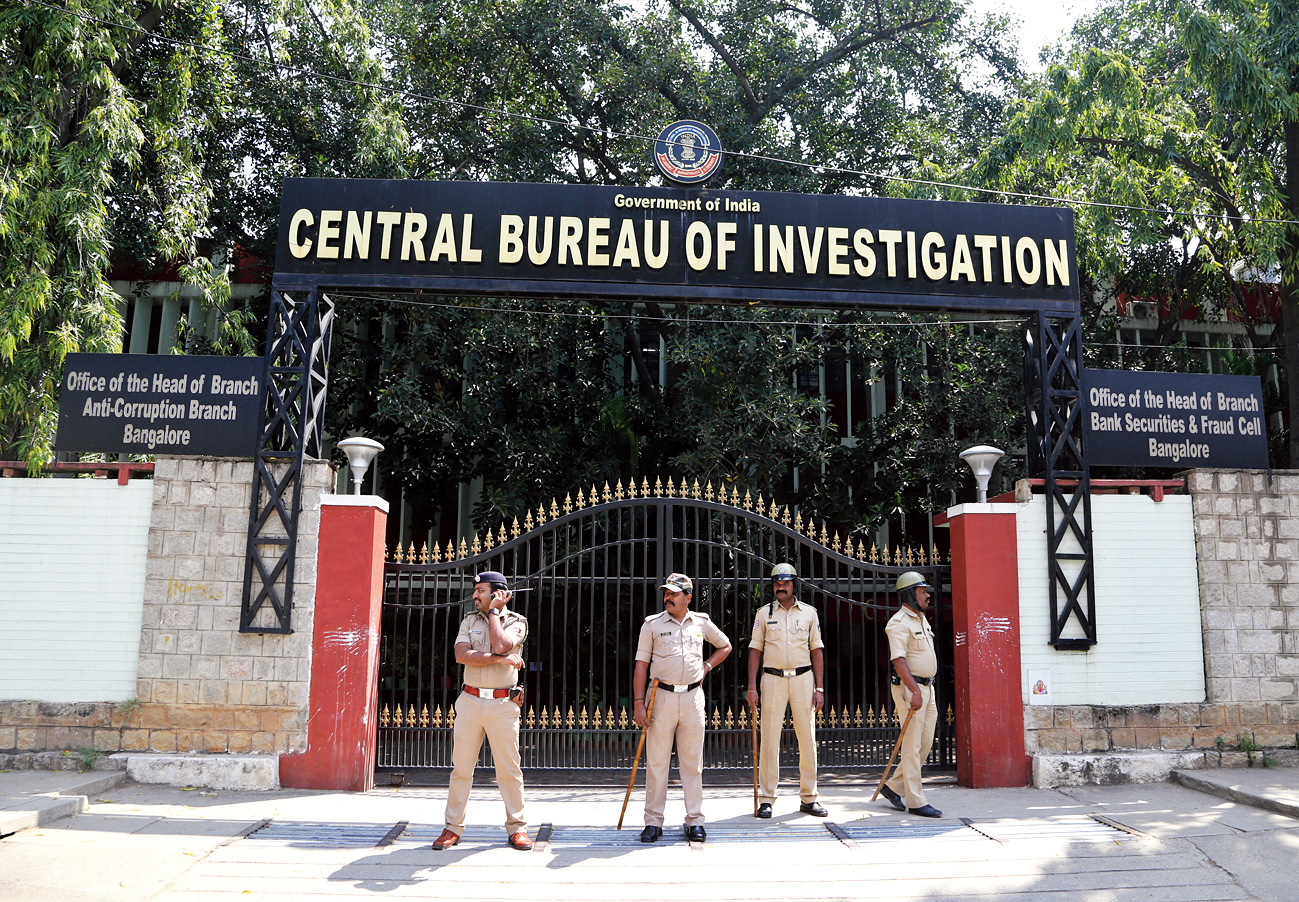

In a pre-dawn crackdown that has no parallel in democratic India, raids were conducted on the headquarters of the Central Bureau of Investigation, the premier anti-corruption agency in the country. The office of the CBI director, Alok Verma, was sealed, and a whole lot of evidence that the agency had gathered was seized. In the morning, orders were served on both Verma and CBI special director and No. 2, Rakesh Asthana, sending them on “leave”, as many as 13 officers were summarily transferred, and CBI joint director, M. Nageshwar Rao, was appointed the interim chief.

The mafia style operation this past week may have seemed like a surreal drama without precedence. But what preceded and followed it, and continues to be the dominant narrative, tells a different story. For the truth is that the Narendra Modi government has pulled off a classic smoke and mirrors act. Smoke and mirrors — defined as “the obscuring or embellishing of the truth of a situation with misleading or irrelevant information”, something that “is intended to make you believe that something is being done or is true when it is not” — has never been as apt a description as in the unfolding drama of the CBI.

The line peddled by the Bharatiya Janata Party spokesmen is that the government had to resort to an ‘extraordinary action’ to meet an ‘extraordinary situation’ caused by internal turmoil within the CBI; a “turf war” between the top two in the agency; an ego clash between two individuals who charged one another with corruption.

On Friday, after the Supreme Court order in response to Verma’s plea against his virtual dismissal, the Union finance minister, Arun Jaitley, came up with a more sophisticated spin. The Supreme Court appointed a retired judge, A.K. Patnaik, to supervise the Central Vigilance Commission probe into the charges of corruption made by Asthana against Verma to be completed in two weeks. It also issued notices to the Centre and the CVC on the plea of the NGO, Common Cause, to set up an SIT to investigate alleged corrupt practices by Asthana.

Clearly pleased that the apex court had not passed any strictures against the government and had not reinstated Verma immediately, Jaitley said, “The Supreme Court ruling is an extremely positive development... All officers of the CBI, particularly the top two, are like Caesar’s wife and must be beyond suspicion.”

Fine words these, except that it conceals a truth that is at the heart of the CBI’s current crisis. The CBI has been mired in controversy before. Previous governments, too, have used the agency to settle political scores, leading to the Supreme Court’s famous “caged parrot” epithet some years ago.

But never before has the top leadership of the government been so blatant in backing one officer over another, and, in the process, brazenly subverting elementary norms that govern any supposedly autonomous entity.

It is no secret that Asthana, a Gujarat-cadre IPS officer, was a favourite of Narendra Modi and Amit Shah when the duo ruled supreme in Gujarat. When a chief minister becomes prime minister, it is only natural for him to get officers of his choice to New Delhi. But procedures have to be followed, criteria have to be met.

The government tried to bypass both. Asthana was first brought in as additional director to the CBI in early 2016. That year, on December 2, the incumbent director, Anil Sinha, was to retire. Just two days before that, the No. 2 in the agency, R.K. Dutta was suddenly transferred to the home ministry. Asthana was then appointed interim director. On December 5, the senior lawyer, Prashant Bhushan, on behalf of Common Cause, moved a PIL in the Supreme Court seeking the appointment of a full-time director of the CBI, and challenging Asthana’s appointment.

It was only after that that the selection committee — comprising the prime minister, the leader of the Opposition and the Chief Justice of India — met and chose the former Delhi police commissioner, Alok Verma, as the new CBI director. Verma assumed office on February 1, 2017, for a fixed two year term.

But in spite of Verma’s appointment, it became clear that the top leadership trusted Asthana much more. He was given charge of all major cases concerning Opposition leaders: Sarada; Narada; the IRCTC case against Lalu Prasad and family; the Aircel-Maxis and INX media cases against P. Chidambaram; the AgustaWestland chopper deal; the Robert Vadra land deal case, you name it. He also had easy access to the PMO and acted as if he were the boss — attending meetings in place of the director and seeking to recruit his own team of officers.

The government may have felt that Verma, out of gratitude for his appointment, would be a willing rubber stamp and let Asthana call the shots. But Verma — mild mannered, but tough underneath — refused to take things lying down. In October 2017, he gave a dissent note to the CVC against the elevation of Asthana to the rank of special director. In his note, Verma pointed out that Asthana was under investigation for allegedly taking a Rs 3.88 crore bribe from the Baroda based Sterling Biotech firm which was facing a case of money laundering running into over Rs 5,000 crore. The CVC overruled Verma’s objections and went ahead with Asthana’s promotion.

Common Cause, once again, moved a PIL against his elevation. Apart from the bribery charge, the PIL also pointed out that Asthana’s son, Ankush, had worked for close to three years as an assistant manager with Sterling Biotech, and the owners of the company had provided hotel accommodation and other facilities gratis for the wedding of Asthana’s daughter in Baroda in late 2016. The Supreme Court, however, went by the CVC’s decision and refused to intervene.

Matters continued to worsen over the months. Finally, on October 23, this year, the CBI divested Asthana of all responsibilities, following investigations into his alleged bribe taking and extortion in half a dozen cases.

Asthana, meanwhile, had hit back by writing to the cabinet secretary, P K Sinha, listing a litany of charges against Verma. Although Verma has so far had an unblemished record, these counter-charges suddenly put them both at par.

This suited the government only too well. Verma had refused to play ball by suffering Asthana’s insubordination. He had irked the government further by meeting Arun Shourie and Prashant Bhushan who sought an investigation into the Rafale deal. Having painted the entire Opposition as corrupt on the basis of CBI cases lodged against them, and having refused to open its own decisions to any investigation or scrutiny, the Modi regime simply could not afford to tolerate a CBI director who showed a hint of spine, who had access to past secrets that the two most powerful people in the country are keen on hiding.

The dramatic crackdown in the middle of the night may have removed the CBI boss for now. But the prime minister’s abject failure to sort out matters before they reached a flashpoint and the subsequent sledgehammer operation also reveal an uncharacteristic sense of panic, a loss of control.

Faced with escalating charges of wrongdoing in cases involving Vijay Mallya, Nirav Modi, Mehul Choksi and, most of all, Anil Ambani and the Rafale imbroglio, Modi apologists take cover in the fact that there is no “smoking gun” evidence so far. The blanket of smoke, after the CBI explosion, has certainly become thick. But it cannot forever obscure the murkiness that lies underneath...