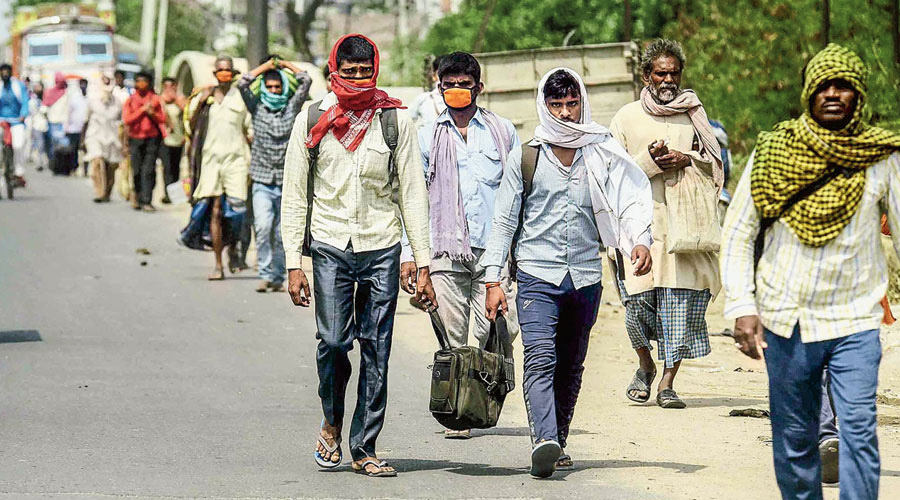

India has a huge number of unorganized workers who do not have a fixed residence in their place of work. They are temporary migrants who move from one job site to another. They have no rights that can be easily established, are paid poor wages and have abysmal working and living conditions. They are a faceless, nameless mass of people who represent the ‘economic untouchables’: the economy needs them, but society refuses to integrate them. The two waves of the pandemic have hurt this section of the population the most. In 2020, thousands of migrants marched barefoot over highways with all their material wealth, journeying home when the lockdown suddenly took away their livelihoods. This year, too, a similar fate struck them during the second wave. The pictures of migrants walking hundreds of miles became the indelible image of Covid-19 in India. A few days ago the Supreme Court pulled up the Centre for still not having created a National Database for Unorganised Workers to facilitate the distribution of benefits like food rations and cash transfers to these workers. The ministry of labour has been ordered to complete the project by July 31. In fact, the ministry had been instructed as far back as in August 2018 to create the portal with an updated registry of all migrant workers. The court used strong words, describing the lapse as unpardonable and indicative of the apathy of the government. It also remarked that the labour ministry was not alive to the concerns of migrant workers. In spite of the order of 2018, the government allocated only 45 crore rupees this year to set up the portal and update the data.

In the context of this failure, three conclusions can be drawn. The first is the sheer inefficiency of the government in not being able to deliver on a low-budget and uncomplicated project. Secondly, this is not an issue of scarce financial resources; rather it is one of insensitivity towards people who have very little say in national politics. The third conclusion emerging from the failure to create the portal goes beyond mere apathy. It is part of a systematic effort to keep the larger working population under stress. The farmers and the workers all represent potential sources of trouble, capable of questioning economic policies that only create ever-widening inequalities in wealth and incomes.