Heinrich Heine, one of the all-time great German writers, has a frighteningly memorable sentence: “Das war ein Vorspiel nur, dort wo man Bücher verbrennt, verbrennt man auch am Ende Menschen (That was only a prelude; where they burn books, they will in the end also burn people).” He was among the other German writers — Maria Remarque, Karl Marx, Albert Einstein and several others — whose books were publicly burnt in May 1933 by the Nazi Students’ Association, the SS and the Hitler Youth. They burnt at the Bebelplatz in Berlin some 20,000 books because these books promoted ideologies and ideas not acceptable to the Nazis. Heine was reacting to the ghastly act.

In Joseph Stalin’s regime, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn was charged with ‘founding a hostile organisation’ and put in the Lubyanka jail. This was in February 1945, just before World War II was to end. He had to watch the victory celebration of the war, in which he had participated as a soldier and risked his life, from behind the muzzle of the window of his prison cell. Later he was sent to the isolated prison forming the subject of his celebrated work, The Gulag Archipelago. He was among the more illustrious of the numberless writers imprisoned and tortured for writing what they had seen.

Autocratic regimes, whether Right or Left, hostile to any kind of criticism, have invariably shown utter disregard for dissenting voices. Of course, this by itself cannot be taken as a defining feature of such regimes; but it certainly is one of their definitive features. If we look at our own treatment of dissenting voices, we do not have much room for taking a morally superior stand. Although most of us may have happily forgotten in recent time that a number of journalists and writers were killed in our country, our report card is not free of blood stains.

Here is a random list of those who got killed because they were working with words — 2014: Tarun Kumar Acharya, M.V.N. Shankar; 2015: Jagendra Singh, Sandeep Kothari, Sanjay Pathak, Hemant Yadav; 2016: Karun Misra, Rajdev Ranjan, Kishore Dave; 2017: Gauri Lankesh, Santanu Bhowmik, Sudip Datta Bhowmik; 2018: Navin Nishchal, Shujaat Bukhari, Muhammad Sohail Khan, Chandan Tiwari. The states in which these killings happened include Odisha, Andhra Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Gujarat, Karnataka, Tripura and Kashmir. This list would be much longer if one were to include the killings of rationalists like Govind Pansare and M.M. Kalburgi. It would be almost unmanageably longer were one to add the names of political workers butchered. The question here is not how or who killed them; it is why they were killed. And the timeless and well-known answer to this question is that they were saying something that was not convenient for the rulers, that their thoughts were seen as ‘dangerous’. Sadly, none of the killings generated as much censure and public debate as they should have. Sadly, again, they passed off as if they were ordinary murders requiring ordinary police inquiry that ends in dusty files becoming dustier as the agony of the families of the victims keeps growing duller and fades one day in the forest of cynicism.

The instances in India during the last several years have by no means been a phenomenon in India alone. The situation in Russia, China, Turkey, Brazil, the East European countries and our neighbour, Bangladesh, has not been different. Even the United States of America, a country that had firmly stood for the freedom of expression throughout the decades of the cold war, has had its share in the suppression of the media; and Donald Trump’s presidency has made that into an art with excellence. Although the news of explosives dispatched to the CNN office last year did not find headlines in our media, it did send shivers down the spine in US media circles.

What is it in the world that has changed so radically in recent years? There is, of course, no easy answer, and one is too close to the new era to be able to comment with much objectivity. Yet, I venture to offer a comment since I cannot accept silencing of dissent and intellectual opposition through violence as acceptable in civilized society. One rather obvious explanation for the growing intolerance in the world is that during the last three decades, nation after nation has moved from the distributive-economic model for elimination of inequalities which a range of Left-oriented regimes and social welfare states traditionally held as sacred to an aspirational-growth model that the conservative political parties and the Right-oriented states have started promoting.

In this shift from the Left-oriented economic views to the Right-oriented economic views, the people in these nations have also gradually gravitated towards the political Right, which in Adolf Hitler’s classic — read infamous — formulation, believes that “the society is like a woman who likes to be tamed and mastered by a strong and powerful leader”. For the last several years, the era of the perceived ‘strong and masterly’ leader has started unfolding in most parts of the world; and, together with this clemency towards violence-prone political regimes, nations have started tolerating extreme Right political parties. The parliamentary elections in Spain held in April resulted in nearly one-tenth of the elected members being from the ultra-Right. On April 27 — the day that Italy has celebrated as its ‘liberation day’ since 1945 — the Italian ultra-Right took out a parade in Milan with banners showing Mussolini and saluted the banner, all in the real Fascist style. In Sweden, France, Germany, Spain, Italy and, of course, Austria, the rise of the ultra-Right during the last few years has further kindled the hopes of these elements. As we saw last month, they united for the purpose of elections to the European Union Parliament and scored an increase in their strength. How Europe copes with the ultra-Right and manages to safeguard the legacy of democracy is another matter. What matters for us in India is that we have not been able to give enough thought to how the transition from our Left economic orientation to the growing-aspiration-based model of development can be negotiated without allowing anti-democratic sentiment to rule our heads and hearts.

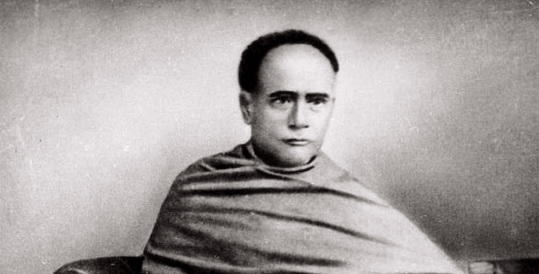

The destruction of the bust of Ishwarchandra Vidyasagar in Calcutta a few weeks back is, to my mind, a clear indication of how intolerance towards diverse ideas and dissent has taken hold of our minds, and how our changing economic wisdom has substantially altered and occluded our idea of democracy. The history of modern India tells us that the Indian renaissance bringing India to the threshold of modernity began in Bengal during the 19th century. The rise of the influential middle class as a major social phenomenon was first seen in Bengal during the twentieth century. The decline of Left politics was seen first in Bengal at the beginning of the present century. Many phenomena that impacted India later, first emerged in Bengal. This time though, what we just saw last month was the destruction of the Vidyasagar statue in Bengal. If that indicates anything, we need to think about what is in store for India. This time it was to symbolize the rise and the mainstreaming of the Right and its doctrine of violence. May 2019 will continue to engage future historians for a long time. Reading Heine again should be of interest to us.

The author is a literary critic and a cultural activist

ganesh_devy@yahoo.com