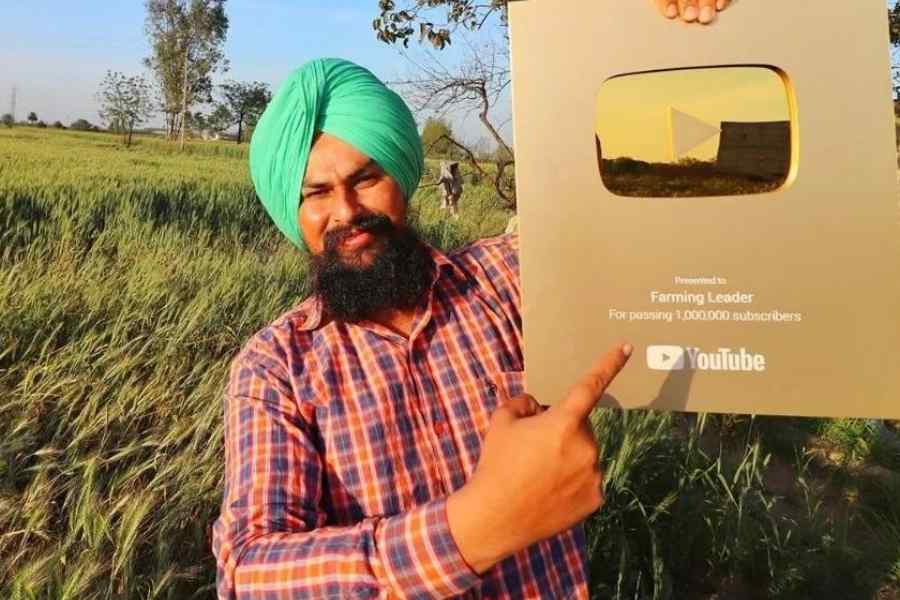

In a year when the Central government decided to try and end what has been a free run for content creators on YouTube, the platform has become an amalgam of so many things that it does seem like India lives and breathes on YouTube. It heralds the post-television era for both newsmakers and news producers, and it offers more public broadcasting in a real sense of the term than the public broadcaster does, much of it produced by the public. There are so many farmers producing farm programming that such channels now have a rating guide to recommend them. It is a source of rural livelihoods. Self-created YouTube influencers are now more courted by the political class during elections than reporters and anchors of TV channels.

The political class is also discovering that you can use the medium to reach voters, unmediated by mainstream media. YouTube’s news and political director, writing for Nieman Reports some time ago, had called it the “flattening of politics”. Connecting on this platform offers far more interactivity to a candidate, apart from being an anytime, anywhere medium for voters to access. It has put an end to TV’s gatekeeping role.

YouTube was founded in 2005, and politicians have been using it since. Narendra Modi launched his YouTube channel in 2007 as the chief minister of Gujarat, Barack Obama’s presidential campaign experimented with it for the 2008 election. This year, more and more politicians in India are using it to connect with voters come elections, even the prime minister reiterated recently that he has been on YouTube now for 15 years.

The Hindu recently worked out, using data from multiple sources, that with over 450 million active users in India, 32.8% of the country’s population is on YouTube. It is a video sharing site which is making television redundant. And, since big tech platforms are tireless strategisers and innovators, the platform for content hosting now also allows Artificial Intelligence-enabled content creation with the YouTube Create app introduced this year.

In comparison with WhatsApp and X (formerly Twitter), it is a platform designed for substance. Even as digital news sites crib about YouTube deciding unilaterally what advertisement rates they will be paid, they know it makes their existence possible. Think about it — if there was no YouTube, there would be no public consumption of free video. When the government denies a film a censor certificate, it ends up on YouTube. How effectively will the government of India be able to police it?

So there is a power shift happening within the media universe from companies to individuals. Newslaundry reported earlier this month that by the time the Adani takeover of NDTV was completed in December 2022, views at NDTV India dropped by more than half to 45 million after anchor Ravish Kumar walked out of the channel the previous month. NDTV, now better financed than before the Adani takeover, has not been able to hold on to its audience.

OTT and digital channels are an important form of space for media creators — news anchors are opting out of their jobs and starting their own channels. But the more this space is claimed and occupied, the more anathema it becomes to governments. Bringing OTT into the ambit of the recently introduced broadcast bill is thus a way of getting to YouTube channels, which, so far, were out of the government’s regulatory ambit. India’s digital realm had no regulator, but now the government has passed laws and given itself powers to make rules. The draft bill, as it has been formulated, provides for 67 (yes, 67) areas where rules will be made later, effectively making new laws via rules.

When you club digital with broadcast you are putting individual video-first journalists with small teams or no team at all on the same footing as mainstream TV ventures. The same broadcast laws (including hiring a grievance redressal officer) will apply to both Ravish Kumar’s YouTube channel as well as to a company like NDTV.

When you step onto Planet YouTube, you discover the tyranny of algorithms. At one of the several panel discussions taking place on the implications of the broadcast bill recently, Barkha Dutt described what this means — essentially, algorithms will decide whether and for what kind of stories you get traffic. YouTube pays content creators for the advertising it puts on their content. That’s what makes it a viable option for individual broadcasters. But there is no transparency in Big Tech on how our numbers are measured, she said. YouTube’s algorithms decide which ads to place, they unilaterally decide what percentage you will get, it is their estimate. They link it to their own way of measuring your audience.

Also, in the face of constant government pressure internationally to compensate news broadcasters, both Facebook and YouTube are set to stop promoting news. Facebook recently took algorithms off news as a programme category with those using Facebook for content promotion being immediately impacted. Echobox which measures social media referrals quantified this. On July 17, 2022, Facebook produced 15.50% of referral traffic for publishers. A little over a year later, on August 3, 2023, this figure dropped to just 4.84%.

Meanwhile, it has totally decentralised the way media works, disrupting the television industry in the process. Over the years, there has been a marketing shift to YouTube via influencers on YouTube and niche YouTube channels. An intermediary such as feedspot.com provides an enabling database for niche advertisers: “over 250k active YouTubers in over 1400 niche categories.” That, then, is what the digital video sharing universe looks like today.

And YouTube has come to host public broadcasting of the kind the government-owned public broadcaster does not offer, where farmers broadcast farm programming from different parts of the country, supplementing their own meagre agricultural incomes in the process with the advertising YouTube gives them.

It actually helps create rural livelihoods, sometimes enabled by district administrations. Indian villages now have YouTubers, and a colourful profile of one such village of 10,000 in Raipur district says there were 40 such creators there, producing videos on everything ranging from Chhattisgarhi folk music to Ram leela re-enactments, to slapstick satire to films. The collector then sanctioned a Rs 25-lakh studio for the village, sensing a new avenue for job creation. One beneficiary reported that he was now saving Rs 5,000 per video in costs, spending Rs 10,000 on a music video and earning one lakh rupees. Elsewhere, in Kaushambi in Uttar Pradesh, a feisty woman entrepreneur, Yashoda Lodhi, is teaching spoken English via a YouTube channel called ‘English with Dehati Madam’.

Essentially, media creation has now become the realm of ordinary Indians with extraordinary gumption.

Sevanti Ninan is a media commentator and was the founder-editor of TheHoot.org