The author is a retired diplomat and currently Director General of the Indian Council of World Affairs

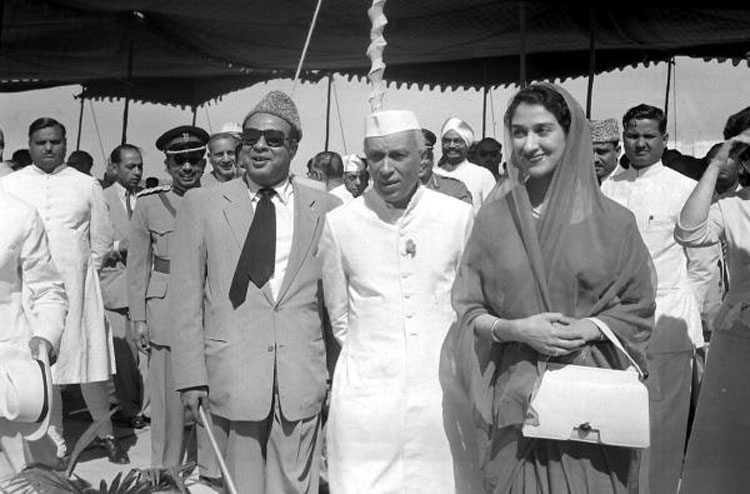

Mohammad Ali Bogra, Pakistan’s prime minister from 1953 to 1955, had an unusual career graph. He was active in pre-1947 Bengal politics in the Muslim League and had joined the Pakistan foreign service after it was formed. He served in the early 1950s as ambassador to Canada and was thereafter in the United States of America as ambassador, when he was called back by the governor general, Ghulam Muhammad, and appointed prime minister in April 1953. There are numerous curious anecdotes about him and his tenure as prime minister, but what also stands out is a summit meeting with the then Indian prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, in New Delhi in May 1955.

Many unusual features usually characterize each India-Pakistan summit. During Bogra’s visit, two stand out. The first of these was that his wife was the subject of a social boycott that extended all the way to New Delhi. A separate story hangs around this. In brief, while posted in Canada he met Aliya — a Lebanese Canadian — who worked in the Pakistan embassy. She moved with him to Washington and thereafter back to Pakistan on his being appointed prime minister. She was initially his social secretary and then his wife. Bogra was already married with two sons from his first wife and the second marriage to a former employee led to widespread indignation in upper-class Karachi circles — largely led by wives of important politicians and civil servants who were close friends of the first Mrs Bogra. A boycott was, in fact, in place of all social or official functions which the new Mrs Bogra was to attend — no other women of standing would be present.

Somewhat unusually, this boycott extended to all the way to Delhi when Bogra visited in mid-May 1955, accompanied by the second Mrs Bogra. All the wives of the high commission officers decided not to attend any function where she would be present, including at the arrival ceremony at the airport. A young diplomat from Pakistan, then posted in Delhi, felt that the boycott was joined in by Indians too since Indira Gandhi, who usually acted as her father’s official hostess, chose to leave Delhi on a tour. In this diplomat’s recollection, with nobody wanting to talk to Mrs Bogra, it was left to Nehru to make conversation with her at an official reception in honour of the visiting prime minister.

This social awkwardness apart, there was a second unusual aspect to the Pakistan prime minister’s visit. The summit was to see if India and Pakistan could find a common position on Jammu and Kashmir, but the visit was overshadowed by another incident.

On May 7, 1955, a few days earlier, a party of the Central Tractor Organization (an organization set up by the World Bank in 1946 to introduce heavy tractors into India) was inspecting farms near the India-Pakistan border at the village Nekowal, Ranbir Singh Pura, Jammu. It was fired upon from the Pakistan side, leading to 12 fatalities. The team from the Central Tractor Organization had a military escort led by a major, S.R. Budhwar, an officer of the Remount Veterinary and Farm Corps, who was also killed. In the exchange of fire, there were Pakistani casualties too, but it was clear that the firing had been initiated by the Pakistan side. These were still the days when the status of the United Nations Military Observer Group in India and Pakistan was recognized by both and its inspection report confirmed that the border violation was from Pakistan and that it was “premeditated”.

From May 9 onwards, the incident was in the front pages of newspapers and a visit to the village by a Central minister and the then prime minister of Jammu and Kashmir, Bakshi Ghulam Mohammad, further underwrote its gravity. By the time the visit of Bogra began from May 14, Nekowal was well known in India and had moved high up on the priority of the summit agenda.

On May 15, Indian press reports quoted a Pakistan high commission press release to the effect that the Pakistan prime minister had expressed regret over the incident to the president of India. In other meetings it was conveyed by Pakistan that a full investigation would be carried out to establish responsibility. In Indian accounts of these meetings, Bogra agreed to pay compensation if the investigation so merited.

On Bogra’s return to Pakistan, however, things changed. Nekowal, Pakistan now held, lay on the Sialkot-Jammu border and was governed by special arrangements which precluded Indian troops from entering it. The responsibility for the skirmish, therefore, was not Pakistan’s but India’s. Although this diffusion of the issue delayed matters, the fact was that the UNMOGIP report had very clearly confirmed a premeditated attack from the Pakistan side.

Bogra himself was soon to be replaced by Chaudhry Mohammad Ali, formerly his finance minister. Nekowal as an issue, however, continued on the India-Pakistan agenda with frequent reminders and protests from the government of India and Nehru himself. Interest in Parliament and in the media had not died out. Possibly what also acted as a point of pressure on Pakistan was the UNMOGIP report. The matter was finally settled over a year after the incident when a payment of Rs 1 lakh was made by the government of Pakistan in August 1956. Interestingly enough, and perhaps inevitably, the payment was termed ‘ex gratia’ and not compensation. This meant that Pakistan did not accept full responsibility for the incident because of its own version of the point to which Indian troops could proceed on the Sialkot- Jammu border. Nevertheless, that the government of Pakistan paid an amount at all was novel.

Since then a great deal has changed. Following the Simla agreement the ‘ceasefire line’ was converted into a ‘Line of Control’ and the UNMOGIP has lost its relevance for India although Pakistan still swears by it. The border, as also the LoC, is fenced, although that has not stopped skirmishes and ambushes. Different interpretations of the boundary between Jammu and West Punjab and Sialkot, however, remain. For Pakistan, this is still a ‘working boundary’ and not the international border, since the territory on the other side is Jammu and Kashmir. For India, this is an international border. Some of the most intense ceasefire violations of the recent past have been in this area.

The Nekowal incident itself is all but forgotten except by the occasional historian and archivist. It remains, nevertheless, possibly the only time Pakistan made a monetary payment to India for acts carried out by its troops even as it evaded responsibility for these acts. And finally there is a border observation post, ‘Budhwar’, in Nekowal village in Ranbir Singh Pura. One would like to think that it is so named in silent remembrance of a soldier escorting a party of civilians trying to see how heavy tractors could increase productivity in a Punjab village.