It’s a paradox of politics that the world’s largest democracy should rely on a feudal fiat in the grim battle against terrorism. In bombing Balakot so that terrorists can never feel secure even in Pakistan’s remote and rocky Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, India should have enjoyed the vigorous support of the 14 million inhabitants of Jammu and Kashmir. Instead, it can cite only an authorization by the flamboyantly styled “Shriman Inder Mahander Rajrajeswar Maharajadhiraj Shri Hari Singhji, Jammu and Kashmir Naresh Tatha Tibbet adi Deshadhipathi, Ruler of Jammu and Kashmir State” on what a British historian called “no more than a printed form, not unlike an application for a driving licence”.

Whether Hari Singh signed the accession document on October 26 or 27, its legality is above question. Its moral validity isn’t. People can depose a ruler; no ruler can abolish the people. Some of the assumptions on which the decision was based no longer exist. The maharaja was desperate to save Kashmir from the savagery of the Pakistan-backed invaders. His prime minister, Mehr Chand Mahajan, warned Jawaharlal Nehru that if India didn’t respond, he would go to Mohammed Ali Jinnah. “Of course, Mahajan, you are not going to Pakistan,” retorted Vallabhbhai Patel. He could say that with confidence because he knew Nehru had forced Sheikh Mohammed Abdullah, the Dogra dynasty’s sworn enemy, on the ruler. Abdullah didn’t get on with Jinnah either. Jinnah, in turn, had been advised that Kashmiris weren’t “true Muslims”. Hari Singh must have signed the accession instrument and appointed his arch-enemy to head the government (relations were “tense and antagonistic” says Karan Singh) with gritted teeth. The Sheikh supported him because he felt that the new nationalism called Kashmiriyat “which posited that Muslims and Hindus in the Kashmir region shared a distinct Kashmiri identity” would be safer in liberal, secular, democratic India than in a dominion born in the crucible of Jinnah’s two-nation theory. The success of Kashmiriyat explains Kashmiri refusal to support Pakistani infiltrators in the Kargil war.

As grenades burst, blood flows and Kashmiris are beaten up, India needs popular sanction for its policies. According to some estimates, the terrorism, insurrection, rebellion, call it what you will, killed 80,000 people between 1989 and 2002 alone. The return to ‘normalcy’ indicated by the promised resumption of talks on the Kartarpur corridor for Sikh pilgrims doesn’t translate into peace on the ground. Villages along the Line of Control report intensified firing. India accuses Pakistan of violating the border ceasefire three to four times a day on average. No doubt the other side paints an equally grim picture. The young mother and her two children aged five years and 10 months who were bombed out of existence on March 1 in Salotri village of Poonch or the 17-year-old youth who was blasted to death in Jammu on Thursday do not interest the applauding galleries packed by a well-heeled business community that has calculated it can maximize profits while the sun of the National Democratic Alliance shines.

In a sense, the problem is self-perpetuating. Separatist sentiment can claim to derive legitimacy from Article 35A and even a drastically attenuated Article 370. But the massive upheaval their abolition is bound to provoke might make the present conflict look like child’s play. The solution (which China has tried in Xinjiang and Tibet) of letting Kashmir be “overrun by people whose sole qualification might be the possession of too much money and nothing else, who might buy up, and get the delectable places”, as Nehru put it when defending Article 35A, could mean worse bloodshed. Ignoring the Pandits’ eviction in 1989-90 and the 2008 furore over allocating 99 acres of forest land in the valley for Hindu pilgrims, the NDA tested the waters three years ago. A think tank reportedly with Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh links challenged Article 35A in the courts. The controversy over the citizenship (amendment) bill confirms that the northeastern states would also resist an influx of outsiders.

But Sheikh Abdullah didn’t see accession in respect of only communications, defence and external affairs as the end of the road. Whether or not he was engaged in conspiracy, two American diplomats he spoke to — Loy Henderson, ambassador to India, and Warren Austin, Security Council representative — confirmed that Indian suspicions about his political ambitions were not unfounded. It may be relevant in this context that he turned down Nehru’s request to place the accession instrument before the constituent assembly in August 1952, probably fearing it might be rejected, a fear Nehru shared. The assembly itself was of dubious standing since the election to it was widely criticized and the ruling National Conference held all 75 seats. This flawed institution finally voted on February 6, 1954 to ratify an instrument that had been signed seven years earlier.

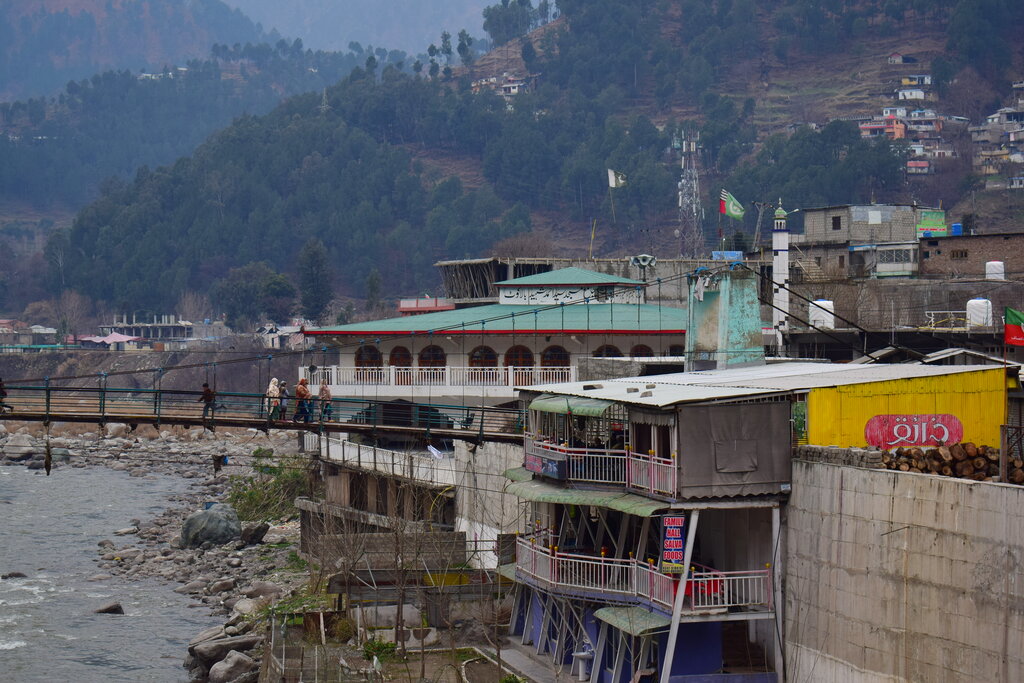

Much water had flowed down the Jhelum and Chenab in those seven years. The Sheikh had been ousted and imprisoned. The wits said his successor, Bakshi Ghulam Mohammed, was Delhi’s golam. Very little remains of the original compact between India and Kashmir. “Article 370 has been reduced to an empty shell... whereby 260 out of 395 Articles of the Indian constitution, 94 out of 97 entries in the Union list and 26 of the 47 entries in the concurrent list, have been extended to the state of Jammu and Kashmir in a brazen manner,” the state High Court Bar Association lamented. The latest affront is from the extension to Kashmir of the new 10 per cent quota for economically weaker sections as well as the Central law making Dalit and tribal state employees eligible for reservation in promotions. The objection is not to the substance of these measures but that such impositions erode Kashmir’s guaranteed autonomy. What P. Chidambaram calls today’s “muscular, militaristic and majoritarian” approach shows no trace of the enlightenment of P.V. Narasimha Rao who replied “the sky’s the limit” when asked how much autonomy Kashmir should enjoy.

There are many reasons for revisiting the circumstances that soured the promise of Kashmir as an enthusiastic junior partner in realizing Nehru’s dream. As A.S. Dulat, the former chief spy, stresses in his book, Kashmir: The Vajpayee Years, “[T]he reason that people in Delhi have reservations about talking to separatists and Pakistanis are the very reasons we need to talk to them for.” There is no other way. Despite Arthur Moore’s claim, which I have quoted before, that “there will never be satisfactory relations between India and Pakistan till the Kashmir issue is amicably settled”, long-embedded communal antagonism is unlikely to ever allow a normal diplomatic relationship between the two countries. The Hindu-Muslim animosity no one mentions will ensure that if it’s not Kashmir, it will be something else. But, yes, Sheikh Abdullah had a point in claiming, “Unless India and Pakistan come close the Kashmir problem will remain.” It’s another way of saying Pakistan can always play the spoiler. That remains a fact of life but the spoiler’s role would be less potent if pitted against an India backed by the popular will in the troubled state.

Kashmiris had no say in the decision that created what a Kashmiri calls “the most densely militarized zone in the world”. That answers Dulat’s question “Why can a Kashmiri not be an Indian?” Lord Mountbatten has been blamed for much, especially over Kashmir. But his reply to Hari Singh accepting Kashmir’s accession makes the sound point that “it should be decided in accordance with the wishes of the people of the state...” Timor Leste and Bangladesh showed that it’s never too late for people’s power to assert itself. That is something New Delhi should bear in mind. It’s also worth asking amidst the din of controversy whether India can’t survive without a reluctant and recalcitrant Kashmir.