The conventional wisdom that governed electoral politics and, indeed, governance in India deemed that election manifestos were purely decorative in nature. They were hurriedly prepared in the run-up to the elections, presented at a media event and then relegated to the archives to be used as reference material for researchers. Devi Lal, the doughty Jat leader from Haryana who rose to become deputy prime minister in the troubled Janata Dal interregnum of 1989-90, even asked quite nonchalantly: “Who reads election manifestos?”

The obvious answer is that very few did and even fewer cared. Far greater attention was paid to the catchy slogans that dominated the public discourse.

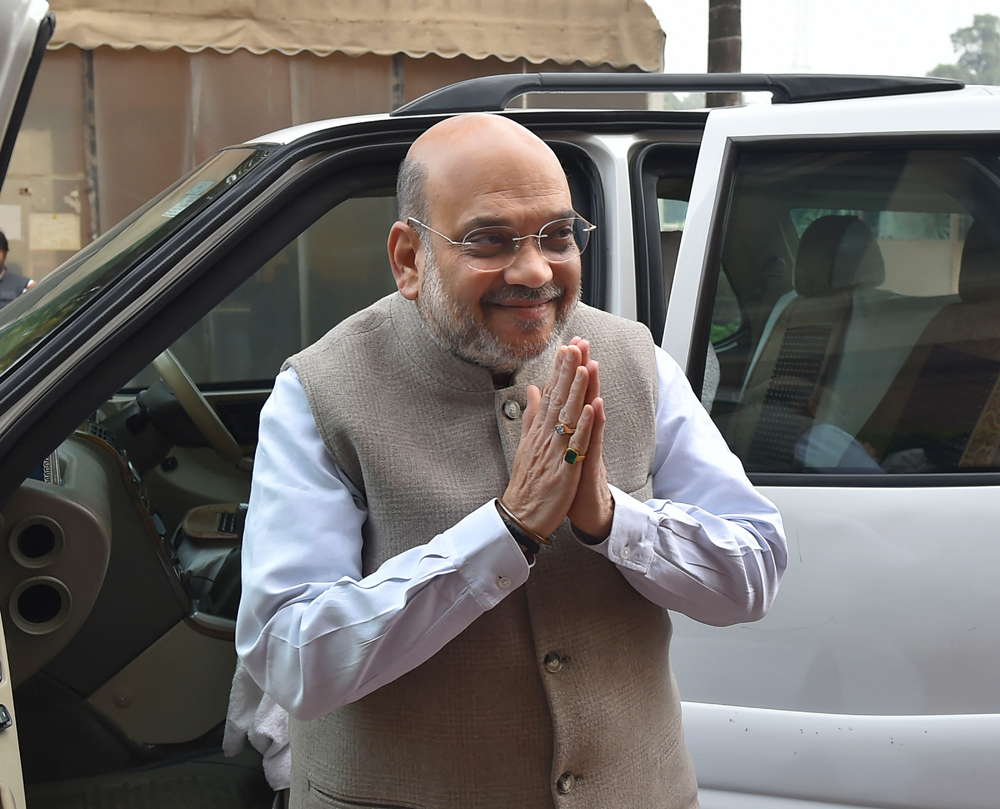

The second innings of Prime Minister Narendra Modi is barely seven months old and it would be grossly premature to even begin assessing it. However, what can be said with a measure of certitude is that it has begun at a searing pace with the home minister, Amit Shah, leading the charge. Shah has done what was considered politically impossible: fulfilling the assurances in the Bharatiya Janata Party manifesto. More to the point, he has started Modi’s second government by systematically ticking off the more ‘ideological’—and, therefore, more contentious — facets of the BJP’s famed distinctiveness. First, there was the triple talaq legislation, the first major reform of Muslim personal laws since the Sharia Act of 1939. This was followed by the abrogation of Article 370, giving a special Constitutional status to Jammu and Kashmir — a move that was spectacular in its audacity. Strictly speaking, the government can’t take direct credit for the Supreme Court verdict that has cleared the path for the construction of a Ram temple in Ayodhya on the disputed site. However, since this was what the BJP had been insisting on since 1988, the verdict has come to be viewed as a vindication of its position.

The fourth big ‘ideological’ step of the BJP government is the contentious citizenship (amendment) bill. Read along with the other measures in the past seven months, it has been viewed by its critics as a decisive step in the construction of a Hinduized polity. The opponents of the bill have viewed it as an attempt to inject a religious dimension in Indian citizenship. It has been suggested that the bill legitimizes the demotion of India’s Muslims to second class citizens — a grave charge that will obviously have to pass exacting scrutiny by the Supreme Court. Indeed, judging by the somewhat half-hearted attempt by the fractured Opposition to counter the bill — Mamata Banerjee may be the only exception — it would seem that Modi’s opponents have reposed their entire faith in the judiciary to bail them out of a larger political failure.

It is not for me to prejudge any Supreme Court verdict. However, from a political perspective, it would seem that the hostile reactions to the bid to fast track the citizenship of non-Muslim refugees from Pakistan, Bangladesh and Afghanistan verge on alarmism.

First, while there is in-principle agreement to providing sanctuary and even citizenship to those who have fled Pakistan, Bangladesh and Afghanistan, it is being suggested that the CAB went a step too far in actually identifying the religious minorities of those countries for special treatment. Why, it has been said, discriminate against Muslims from these Islamic countries who may want to assume Indian citizenship?

Although this has not been explicitly stated, the CAB has taken a cue from the definition of refugee in the Geneva Convention of 1951. According to the Convention, a refugee is a person who “owing to well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion, is outside the country of his nationality and is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to avail himself of the protection of that country...” In short, rather than bank on generalities that obfuscate cruel realities, the internationally accepted norm permits a more specific identification of the persecuted groups.

The reality of religious minorities — more specifically, Hindus, Buddhists, Sikhs, Jains, Christians and Parsis — being vulnerable on account of their professed faith has been well documented. This includes Bangladesh where, despite the non-sectarian approach of Sheikh Hasina Wajed’s government, the State has found it difficult to accord protection and security to small communities of Hindus, especially in the smaller towns and villages. To deny the realities of persecution of religious minorities is to perpetuate a climate of denial on the specious ground that India is a secular country. India did not choose the specificities of intolerance in the three countries and there is no reason why the nature of the Indian State stands to be compromised by recognizing the communalism of other countries.

The issue, however, is not one of asylum alone. In the past, India has given political asylum to Tibetans and to Bangladeshi notables such as Taslima Nasreen. Following the assassination of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, Wajed was granted asylum in Delhi. This is also the case with various Afghans who fled their country after the Taliban takeover. During the military rule, there were a clutch of political refugees from Myanmar in India. This practice is unlikely to be discontinued with the passage of the CAB.

The CAB departs from earlier versions of the Citizenship Act by according instant Indian citizenship to members of the minority communities who had fled religious persecution. It attempts to draw a legitimate distinction between specified refugees and migrants, whether legal or illegal. Is this process of naturalization justified? In the United States of America, refugees are accorded “temporary protected status” and in the United Kingdom they have “discretionary leave to remain”. Should India persist with such a long-term visa approach? Why should the refugees not be encouraged to return to their original homes and view their stay in India as temporary as, say, the Tibetan refugees have done?

In his work, Rethinking Asylum (2009), the scholar, Matthew E. Price, noted: “When people are persecuted… they not only face a threat to their bodily integrity or liberty; they are also effectively expelled from their political communities. They are not only victims but exiles. Asylum responds not only to victims’ need for protection, but also to their need for political standing, by extending membership in a new political community.” The CAB has proceeded on the belief that the minorities from the three countries have no future left in their original homes and that they deserve a new beginning as full citizens in Mother India. Yes, this is a ‘right of return’ approach, but not one that emulates Israel’s policy of granting citizenship to all Jews, whether persecuted or otherwise. More to the point, by granting important exemptions in Northeast India, it has sought to take into account the vulnerabilities of indigenous peoples who have been adversely affected by a silent demographic transformation.

The furore over the CAB has resurrected the forgotten histories of the Partition; it has revived the abstruse debate over the ‘idea of India’; and it has even brought to the fore questions on India’s national sovereignty. Such debates are always instructive and educative — not least the unending lessons on Hitler’s Germany — but they seem to be peripherally concerned with the lives, feelings and future of uprooted peoples who have a passionate commitment to India and see it as their natural homeland. The scholarly debates about constitutionalism and secularism seem to ignore the sentiments upon which Indian nationhood rests. It always helps to keep those in mind too.