In most democracies, whether in Nevada or Nawada, political assessments are invariably shaped by media narratives and, increasingly, opinion polls. Last Tuesday night, in a nail-biting finish around midnight, the Janata Dal (United)-Bharatiya Janata Party-led National Democratic Alliance narrowly prevailed over the Rashtriya Janata Dal-Congress-Left parties’ Mahagathbandhan in Bihar. In political terms, the outcome of any state assembly election is significant. The Bihar election was additionally significant for two reasons.

First, the performance of the BJP in nearly all the assembly elections since the general election of 2019 had been either poor or indifferent. It was conclusively defeated by the Jharkhand Mukti Morcha-Congress alliance in Jharkhand, with its sitting chief minister losing his own seat. It lost its majority in Haryana and had to cobble together a post-poll alliance with a regional party to stay in government. Its high-voltage campaign against the Aam Aadmi Party government secured it a higher vote share but yielded only a few additional seats. And, although it clearly won the Maharashtra assembly election in alliance with the Shiv Sena, it failed to accommodate the ambitions of Uddhav Thackeray and had to be content sitting in the Opposition. To compound its woes, the loss of its long-term ally in Maharashtra was followed by the desertion of the Shiromani Akali Dal in Punjab of the NDA over the reforms in agricultural marketing. In short, although there was no danger to the stability of the Narendra Modi government at the Centre, the impression that the BJP as a party was losing momentum had started gaining ground.

Secondly, the Bihar poll was the first occasion after the Covid-19 pandemic that public opinion on the measures taken by both the Centre and the state were being tested. This test was extremely significant. Beginning with the 21-day national lockdown, the pandemic had resulted in a massive disruption in the lives of nearly every citizen. The loss of casual jobs in the cities resulting in the mass migration of labour had affected Bihar — a state where a disproportionate number of people earn their livelihood in other parts of India — significantly. The disruption of livelihood and the impact on rural communities were bound to have a larger political impact. Bihar was the first test of whether or not the disruption and the government’s handling of this crisis had triggered a fierce anti-government mood. Just as the 2017 assembly election in Uttar Pradesh was the big test of how people had responded to the unsettling effects of the November 2016 demonetization, the Bihar assembly poll became the crucial Covid-19 test. It was an election to elect a government in Patna, but it was simultaneously a parallel verdict on the quality of the Centre’s response to the pandemic.

The expectations of the outcome of an assembly election are only nominally determined by comparisons with earlier electoral verdicts. In the case of Bihar, this assessment was further diluted by the fact that the alignments that contributed to the BJP’s defeat in 2015 had been turned upside down by events. Consequently, despite the facile use of the 2019 general election outcome as a point of reference, this was an election where expectations were based less on statistical data and more on subjective, anecdotal evidence culled through the media.

A perusal of the media during the election campaign suggested a journalistic consensus on two points.

There was, first, a broad agreement that the chief minister, Nitish Kumar, was becoming a drag on the NDA campaign for re-election. There were no substantial charges of corruption against the state administration in the matter of relief distribution during the pandemic. Rather, the disquiet seemed to centre on the chief minister’s aloofness — often contrasted with the personal presence of the UP chief minister, Yogi Adityanath, at problem points — and his steadfast refusal to interact with the media. The alleged disdain for the media was contrasted with Tejashwi Yadav’s open house, something he has inherited from his father, Lalu Prasad.

Secondly, despite the fact that the RJD seemed to bank on its traditional Muslim-Yadav social alliance in the matter of ticket distribution, the media narrative suggested that the MY social base had been substantially enlarged to accommodate all castes. In particular, the Mahagathbandhan’s promise to deliver 10 lakh government jobs was said to have tipped the scales quite decisively against Nitish Kumar and crystallized the anti-incumbency.

An associated feature of the election that warrants emphasis is the exit poll findings. The exit polls, released after the conclusion of the final round of polling on November 7, were heavily weighed against the NDA. The polls also contained the clear suggestion that counting day would see a clear and emphatic verdict in favour of the Mahagathbandhan. It was suggested that Nitish Kumar’s departure after some 15 years as chief minister was assured.

On November 10, both pundits and politicians switched on their TV sets with the full expectation that the rout of the NDA in adjoining Jharkhand was going to be repeated in Bihar.

With the benefit of hindsight, it would seem that the pollsters erred in assuming that those who spoke the loudest represented the feelings on the ground. The Mahagathbandhan was blessed with the support of the assertive MY combine, articulate sections of the Left that commands considerable influence in the media, and the Congress. On top of that, the NDA campaign lacked synergy and coordination, with the BJP and JD(U) fighting separate campaigns. Taken together, the assertiveness of the Mahagathbandhan camp ensured that the silence of many others was interpreted as acquiescence. In particular, the pollsters and the media appear to have seriously discounted the big support for the NDA among the extremely backward castes and women voters. The turnout figures suggested that women participation in the polls exceeded the male turnout by nearly five per cent. The result was that the NDA support was underestimated by the pollsters in a similar way as Donald Trump’s support base was insufficiently factored in during the presidential elections in the United States of America.

There was another conceptual fallacy. The poll data indicated that the support for the BJP was holding in the constituencies it was contesting. This put a big question mark on the nature and extent of anti-incumbency. The BJP was an important partner in the Nitish Kumar government since the JD(U) reverted to the NDA in 2017. Therefore, it was inherently illogical to assume that popular resentment against the state government would be carefully selective in nature and leave the BJP unscathed. In the election, the final tally for the JD(U) showed a dip and the BJP emerged as the clear senior partner of the alliance. But this decline owed almost entirely to the votes taken away by Chirag Paswan’s Lok Janshakti Party that played spoiler, taking away votes but not winning seats. It corresponded to the loss of RJD and Congress seats in the Seemanchal region thanks to the spectacular support secured by the All India Majlis-e-Ittehadul Muslimeen among Muslim voters.

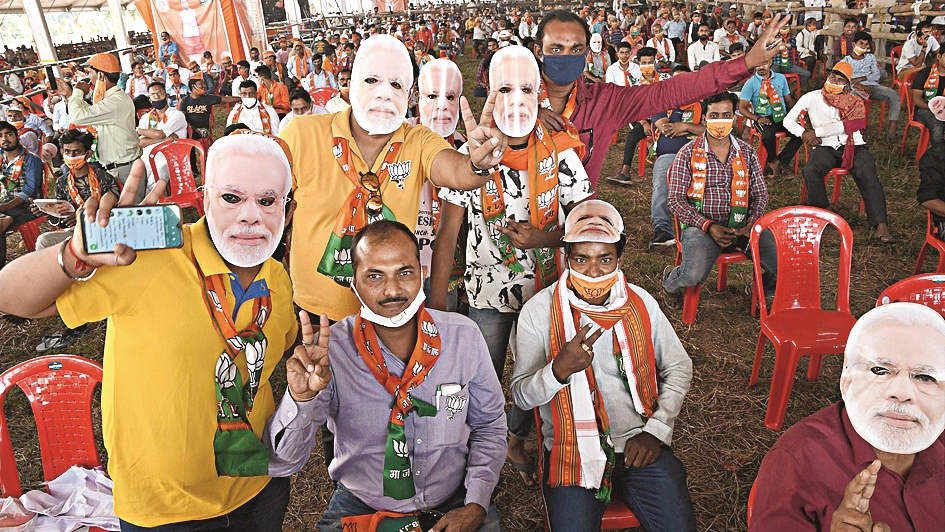

The Bihar electorate gave a narrow verdict in favour of the NDA, defying the prevailing one-sided narrative. The outcome was riddled by many what-ifs — an inevitable consequence of the many spoilers in the race. Overall, however, the results indicated that the pandemic, while hugely disruptive in different spheres, hasn’t quite broken the mould of politics. Above all, the outcome pointed to the continuing relevance of the prime minister in national life and, through him, the unrelenting forward march of the BJP. Since 1990, regional parties have dominated Bihar. This is the first election where a national party has staged a comeback since the Congress decline three decades ago.