Elections can be, in a manner of speaking, occasions for diagnosis and prescription —what’s wrong, what can right it. The people do it, and they do it very often with contrary, even conflicting, assessments of disease and cure. Bihar has lived a schizophrenia for three decades now, bossed in equal measure by two remarkably different men. One, a man of spellbinding charisma and chutzpah who came from nowhere to unleash a ruling manner all his own. Subaltern hero, unshakeable guardian of communal concord, a captivating political entity. But he was woefully lost on governance and often in abject abuse of power. The other, an introvert, almost babu-like of mien, a dour doer, who made correction and revival his mission, a power-beaver adept at locating the means to back his ambition. But he turned out a whimsical proposition, implacably averse to conference, loose on convictions and so spectacularly promiscuous to the purposes of personal power that he lost way and political credibility to the left and right of him. Neither Lalu Prasad nor Nitish Kumar brought to the table what they began by promising its people: ‘Naya Bihar’.

For the better part, this piece must be a repetition of things already said, for Bihar often seems struck by amnesia over its own sorry past; the more things refuse to change, the more they seem to forget what hasn’t, the more they remain swayed on the disarrayed booty of their unfulfillments. We can still be moved and motivated by the promise of drinking water, as if it were a promise of magical novelty.

The ‘Naya Bihar’ slogan is an old one. Every time it rings off a new throat, Biharis begin to stir with hope like only the hopeless can — this time, surely. They’ve discovered, unfailingly, that the shimmer that promised to relieve them of their scorched lives was a mirage, no more. I am part of the ineffable construct of what it must mean to be a Bihari. I can begin to exult in the smallest things at home — a length of pucca road, a stable hour of electricity, a school that has students and teachers in it, a health centre that isn’t padlocked, an office that isn’t a runaround, an officer who minds an office. Can that happen? And when that happens, will it last? The Bihari cheer always comes stained with doubt: how real or durable can any of this be? That doubt has reliably and regularly choked the prospect of cheer.

Bihar was never at a loss for those who set out to build it. In the narrow firmament of Bihari consciousness, they make a clotted constellation of visionaries and builders, reformists and revolutionaries, samaritans and messiahs, charmers and charlatans. Sri Krishna Sinha and Anugrah Narayan Sinha, Jaya Prakash Narayan and Karpoori Thakur, Ram Lakhan Singh Yadav and Jagannath Mishra. They have either been forgotten, some mercifully, or live on in dust-ridden memorial halls and rent-a-crowd commemorations. Or in disregarded town squares as busts routinely shat upon by birds. For all the retrospective reputation they have come to acquire, the gifts of Bihar’s league of legends don’t add up to much.

I have often found myself collared for being harsh on Bihar and its people — no less because I am also non-resident — but I see no merit in romancing what is wrong with Bihar and Biharis. Much is. And correction lies with them, not only with the political order, which often bears disproportionate burdens of blame. I have often been tempted to quote to my critics passages from a speech the Nigerian Nobel laureate, Chinua Achebe, made to an audience in Paris. It was a discourse titled “Africa is People” and it should rank as compulsory reading for anyone trying to understand the complexities of our world. I merely quote this: “I am not an apologist for Africa’s many failings. And I am hard-headed enough to realise that we must not be soft on them, must never go out to justify them. But I am also rational enough to realise that we should strive to understand our failings objectively and not simply swallow the mystifications and mythologies cooked up by those whose goodwill we have every reason to suspect... I understand and accept the logic that if a country mismanages its resources it should be prepared to face the music of hard times.”

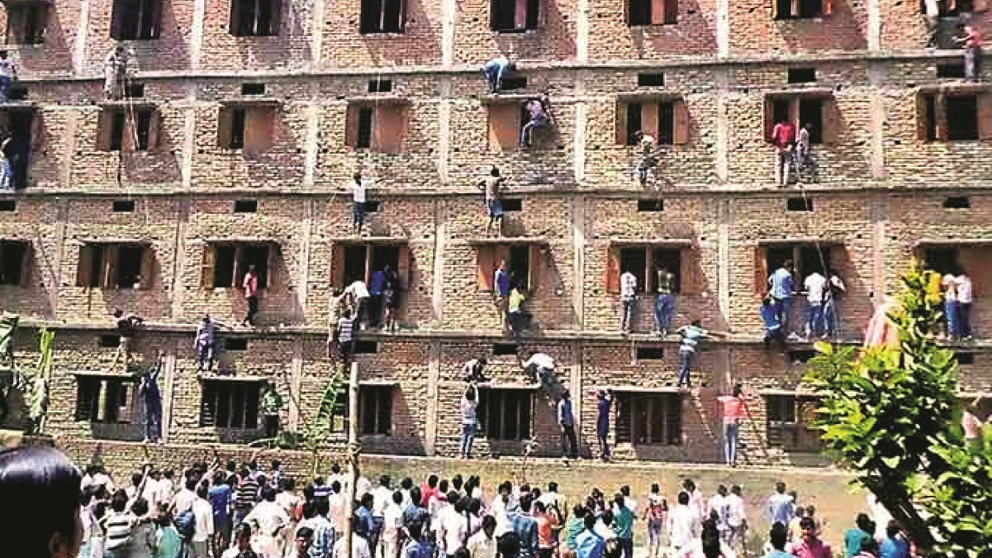

Biharis owe to themselves the favour of better sense. It is not caste and its embedded ills and impediments that I refer to; caste engulfs a wider geography than Bihar and its resolutions will require civilizational time and tussle. I refer to fundamental, quotidian things. Biharis need to tell themselves it does their wards no good to be helped to cheat their way through examinations. That it is not parental duty to search out and bribe examiners to up their grades. That it is not a thing of pride to game the system they are part of, to draw public salaries as doctors and teachers and render no public service in return. That the promise of a government job is not a freebie; it is a job, an undertaking, it needs to be done in return for a livelihood. That discarding masks and distancing during a raging epidemic is not bravado. A good place for us to start would be to stop imagining the world to be shaped like a spittoon. The mouthfuls of masticated paan Biharis are wont to spit any and everywhere as right and ritual of who we are must rank high on the catalogue of uncivil liberties we feel entitled to. To have a dual-carriageway in Bihar becomes a challenge to finding innovative ways of violating the one-way regime. To find a padded seat on a bus becomes an invitation to stab it and rip the foam. Very often, the delight of deflowering virgin foam is reserved for those who bother squeezing into buses, the best seats may still be right on top, whether the insides are entirely taken or not. Better sense, anyone? Nonsense, just keep it to yourself. There is that standing joke about Bihar and Japan and which can potentially become which; Japan turning into Bihar is swifter done.

Bihar is voting again. And once again new-fangled themes of ‘Naya Bihar’ are oozing off chopper missions, boxed confetti from the last campaign unpacked and set afloat anew. The faithful are elated to reach out for a staleness whose stench they’ve turned inured to: this time, surely. Irrespective of who wins Bihar next week, the dawn of the promised newness is as unlikely as a cuckoo spawning swans. It isn’t for the politicians to usher. It isn’t coming until Biharis diagnose their own schizophrenia — the fracture between what they might desire and how they debilitate it — and write a prescription to themselves.

sankarshan.thakur@abp.in