As the death and the devastation from Israel’s bombardment of Gaza continue to mount, the global diplomatic community is beginning to swing into action. The United States of America’s secretary of state, Antony Blinken, is in the Middle East, meeting multiple regional leaders; the European Commission’s boss, Ursula von der Leyen, has visited Israel; some reports suggest that the US president, Joe Biden, might travel to Israel soon. Amid all this, India has largely kept its distance. Narendra Modi condemned the Hamas attacks on Israel, decrying them as acts of terrorism. After several days, the ministry of external affairs added its condemnation of the attack while emphasising that India remains committed to a two-state solution. New Delhi’s largely hands-off approach is perhaps driven by a desire to not take the geopolitical risk of taking a strong stance on a conflict that multiple world powers have failed to resolve for 75 years. But this is a mistaken strategy.

Unlike Russia’s war on Ukraine, where too New Delhi has attempted to sit on the sidelines, the Israel-Hamas war has more direct and serious consequences for India. If Israel’s bombardment continues unabated, and if it invades Gaza with ground troops, it is likely that Iran-backed groups in the region — such as the Lebanon-based Hezbollah — that draw their legitimacy in large part from their support for the Palestinian cause will feel compelled to join the conflict. And if the war expands, the nearly eight million Indians living in the Middle East could be directly affected. With the US moving its naval forces near Israel, the prospects of the conflagration extending to the seas cannot be dismissed. If shipping lanes, including the Suez Canal, are impacted, trade will take a hit, oil prices will rise, and inflation, still above 5% in India, will soar. The religious overtones of the current conflict, coupled with the Islamophobia that supporters of Mr Modi’s government peddle, could also add to the divisive rhetoric in India which the country must stay wary of ahead of the Lok Sabha elections.

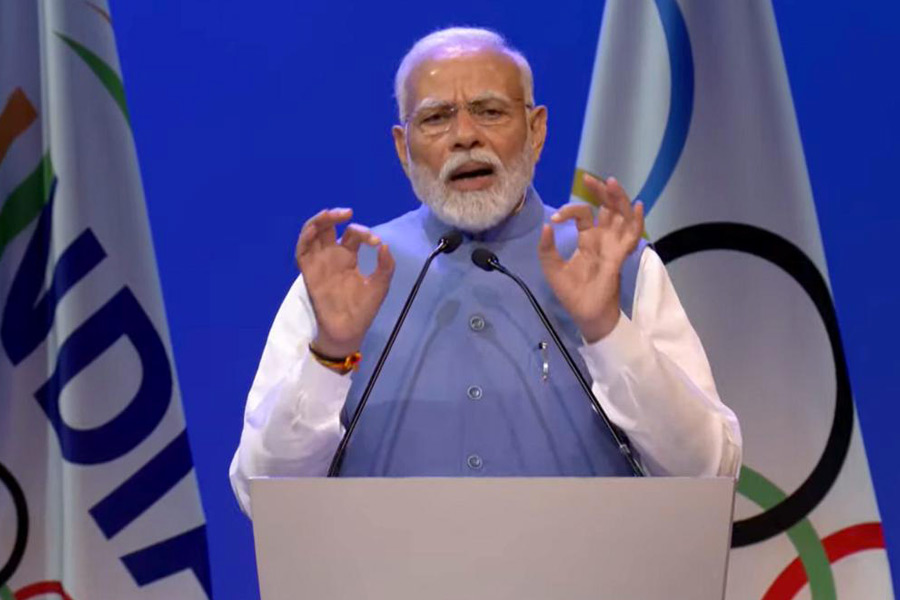

But there is another reason why India can and must take a more proactive role in trying to end the war on Gaza. Mr Modi is a rare head of government who counts both the Israeli prime minister, Benjamin Netanyahu, and the most powerful Arab leaders, such as Saudi Arabia’s crown prince, Mohammed bin Salman, and the United Arab Emirates’ president, Mohammed bin Zayed, as good friends. Mr Modi must use his influence to seek dialogue. His government routinely insists that Mr Modi is among the world’s most respected leaders and that India’s global stature has grown under him. Now is the time for him to prove that.