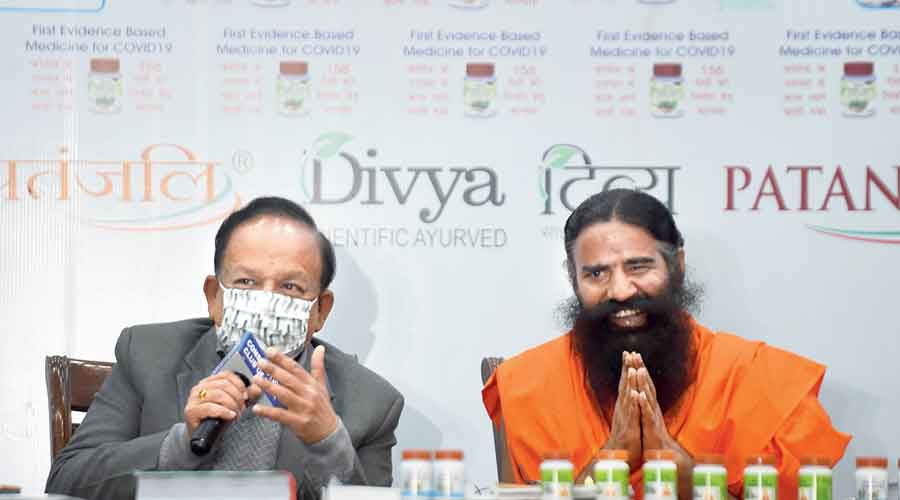

In June 2020, Patanjali Ayurved, an Indian packaged goods company, launched Coronil, an ayurvedic medication. It was marketed as a treatment for respiratory diseases, including Covid-19. Initially, it drew a lukewarm response but by July its hashtags were made to trend on social media platforms. By October, the purported herbal remedy recorded sales of Rs 250 crore. The readiness of the people to believe in a ‘cure’ for Covid-19 and then actually use it aptly illustrates the contours of the ‘attention economy’ created by modern technology.

The hallmark of the internet age has not only been the rise of convenient and boundless information but also the scarcity of human attention. Our attention is now a valuable commodity, harvested by technology companies to keep us trapped in a spiral of infinite searching and scrolling. Several of these attention-capturing tricks have been borrowed from the gambling industry that harness our brain’s dopamine pathways and encourage instant reward-based behaviour.

The technology companies, enabled by social media platforms, engage in subtle techniques of psychological manipulation, plunging us into a world structured to prioritize not the truth but whatever content is most compelling to us. The result is a proliferation of misinformation, fake news and techniques like bot-swarming whereby fake online accounts are created to give the impression that a large number of people support a given position. A study by Benjamin Strick, a digital investigator, suggests a substantial impact of automated bots in amplifying the hashtag, #AmitShahInBengal, on February 18, 2021 in the run-up to the West Bengal elections.

The attention economy also promotes a culture of fear, an effective emotion to leverage, especially in an environment of limited and fractured attention. Nothing exemplifies this more than WhatsApp, which delivers an onslaught of misinformation directly to millions of Indians. The misinformation strategy on WhatsApp is effective because messages are forwarded and re-forwarded by friends and family who are otherwise considered as credible sources of information.

A study by the Indian Institute of Technology, Kharagpur and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology looked into the pernicious use of WhatsApp in India for the spread of Islamophobia with topics such as “Love jihad”, “Kerala Riots” and “Islamisation of Bengal”. The study reviewed two million posts of 5,000 WhatsApp groups and found that fear speech spreads faster, keeps circulating for much longer than non-fear speech, and is amplified by the strategic use of emojis.

Amplification of fear and false content is rampant on YouTube too. Take, for instance, the genre of Hindutva pop music, a cocktail of ‘DJ music,’ techno-beats and bhajans, which openly calls for religious war against Islam and Muslims. Recently, propaganda-spewing YouTube channels camouflaging as news channels had sprung up in the run-up to the West Bengal elections. These channels regularly peddle fabricated news and conduct dubious opinion polls to muddy the difference between facts and falsehoods, a distinction that few are equipped to make in the current media environment. This is further complicated by the erosion of trust in long-standing public institutions. Google search results or Facebook newsfeed of friends are deemed to be trustworthy sources of news today. What counts as a fact is merely a view that someone feels ought to be true, and technology has made it easier for these ‘facts’ to circulate expansively. Experts are certified by high Google search ranks or by the number of Twitter followers. What matters is a loud voice that disrupts the flow of the narrative rather than a substantial engagement with facts.

The constant undermining of institutions distort and demean public debate, contributing to a hate-filled, divisive politics. History offers a reminder of what could be an outcome of such divisiveness. During the 1994 genocide in Rwanda, the vitriolic propaganda of the radio station, RTML, in inciting Rwandan Hutus to attack the Tutsi minority serves as a stark reminder about the dangers of misinformation and fake news.

The brave new world of today’s information age, however, was born not in the Silicon Valley but around 1933 in Berlin. With the assistance of IBM’s Hollerith machine — an electro-mechanical punch card tabulator — the Nazis operated a surveillance State based on citizens’ demographic, financial and other information. This classification system found its concrete manifestation among the concentration camp prisoners who had a five-digit Hollerith number tattooed onto their forearms. The journalist, Edwin Black, in his study of IBM’s involvement in Nazi Germany, wondered why IBM got involved in the market of fascist death camps. It was “never about Nazism,” he argues, “... never about anti-Semitism. It was always about the money.” Today, when new technologies threaten to remake us into disposable commodities, we can only look back on what the Nazis could accomplish prior to the information age.

The question, then, is not whether this economy is convenient or creepy but a more fundamental one about who we are and who we might become in a world that increasingly blurs the line between the physical and the digital. Moving forward, we need to recognize our complicity in delivering our own data to a handful of corporations that fuel this data-driven economic model. Until that happens, ascribing blame to corrupt politicians, the tech industry, or to the prevailing economic system will not accomplish much. The problem, as often is, starts with us.