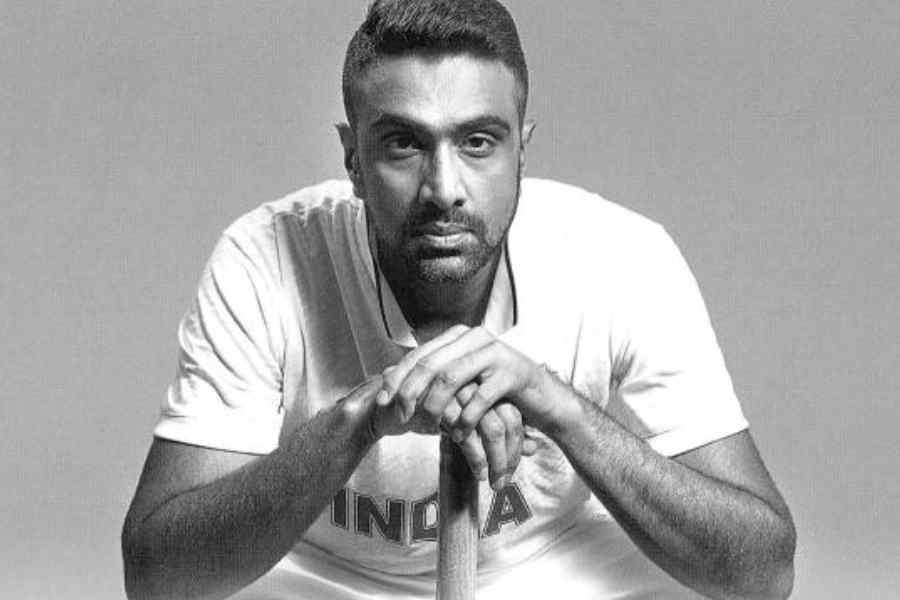

When I saw the cover of R. Ashwin’s cricketing memoir, I was struck by the fact that it had the author in whites, sitting with his hands clasped expectantly around the handle of a bat. It was as if he was waiting for a wicket to fall, to stride purposefully from the dressing room into the ground.

Now I understand that Ashwin can bat. Long before his memoir was published, it was common knowledge that in schoolboy cricket he was known more for his ability to score runs than take wickets. I haven’t myself seen Ashwin play much in the flesh — I mostly watch Test cricket and, for some reason, Bangalore doesn’t get to host Test matches nowadays — yet have abiding memories of watching him on television, bat in hand. In my mind’s eye, I can see him stand tall to a fast bowler and force the ball elegantly off the back foot past point. And I can see him skip deftly down the track to the spinner and loft the ball over the bowler’s head to the sight screen.

Neither of these two shots figured much in what may be the two most consequential innings played by Ashwin in Test cricket. These took place on consecutive months, January and February 2021, on different grounds and against different opponents. In the first of these we had Ashwin, with Hanuma Vihari, stave off a hostile Australian attack at the Sydney Cricket Ground to stay together for forty overs and take their side to an epic draw. In that innings, Ashwin was either seen defending stoutly on the front foot or evading adroitly on the back foot. In between overs, these two defenders of India’s honour had long chats, which were later revealed to be in Tamil, a fact that may have pleased the habitués of Chepauk while offending the ideological descendants of Potti Sriramulu.

The second innings I have in mind was played against England on Ashwin’s home ground. India had a comfortable first-innings lead, yet in their second knock were tottering at 106 for 6. This was when Ashwin came in and in partnerships with Kohli, Kuldeep, Ishant, and Siraj, took India to a total of 286 from where they were to win easily. Ashwin himself scored a century in which I recall no backfoot forces on the off-side, only a few defensive prods and the odd lofted shot, but plenty of ferocious sweeps behind and in front of square. This time, and although it was Chepauk, surely no Tamil was spoken between overs.

I know Ashwin can bat. And those who shall buy his book know it too. All the same, in the history of Indian cricket, Ashwin will be remembered more for his skill with the ball. Why would the taker of more than five hundred Test wickets, the man who has won more Test matches for India than anyone apart from Anil Kumble, write his autobiography and have it printed, published, and publicised with him holding a bat on the cover? I have never met Ashwin but from what I have read and heard of him he is a man with firm and considered opinions. It is thus fairly certain that the image was chosen not by the publisher, nor by the author’s writing collaborator, Sidharth Monga, but by Ashwin himself. Why then did he want a cover with him holding a bat rather than a ball?

I cannot offer a definitive answer to this question (though perhaps in time Ashwin might). I can, however, speculate. Was there a coded message in that photograph, or perhaps several? Was Ashwin trying to draw our attention to the cruel fact that in the reward system of world (and perhaps especially Indian) cricket, it is batters who get more money, more fame, more fan adoration, more endorsements, more TV endorsements, more Player of the Match and Player of the Series awards, more requests for selfies and autographs, than bowlers?

That batters are the pampered elite of the game and bowlers the overworked subalterns is a truth that (alas) is far from universally acknowledged. I have polemicized against this biased reward system myself, but to little avail. Was Ashwin, through his choice of photograph and his far greater standing in the game, making the point more delicately, more subtly?

I have spoken of how, in material terms, match-winning batters get far more out of the game than do match-winning bowlers. Depressingly, this discrimination goes beyond mere matters of money. The batters, Steve Waugh and Ricky Ponting, captained Australia in fifty-seven and seventy-seven Tests, respectively, while Shane Warne was never given this responsibility at all. Now Warne was a brilliant cricket tactician (as he showed in other, lesser, teams he led) and I have no doubt that he would have been an even more successful Test captain than Waugh or Ponting.

This bias is present in Indian captaincy choices as well. That Virat Kohli has led India in sixty-eight Tests and Rohit Sharma in sixteen, while Ashwin has never captained India, may also be at least partly attributed to the fact that the first two are batters and the last-named principally a bowler. And yet we know Ashwin to be one of the most intelligent cricketers to have played for India. It is reasonably certain that had the Madras man got the chance to captain his country, he would have made a decent fist of it. Certainly, the examples of England’s Ray Illingworth and Australia’s Richie Benaud show that spin bowlers can make for outstanding Test captains.

I doubt that Ashwin’s choice of cover photograph is any sort of signal about his (past or present) captaincy ambitions. He seems too decent a man for that. The first speculation may be more plausible; that he is making us more aware of the generic biases in the ways in which batters and bowlers are treated on and off the field. And there may be a third reason; that Ashwin genuinely loves to bat. So, by the way, did Shane Warne and Anil Kumble. It was the former’s abiding regret that though he made twelve Test fifties, his highest score was 99, while the latter must surely cherish the fact that he (at least once) achieved a landmark that his great Australian contemporary failed to get to.

Nonetheless, it is worth noting in this regard that of the five books authored by (or ghosted for) Warne, two have merely his face on it, while three show him bowling or having taken a wicket. We await a memoir by Kumble; as and when it comes, it is unlikely to carry a cover photograph showing the taker of 619 Test wickets holding a bat.

The greatest living cricket writer once wrote a whole book about a single cricket photograph. It is a wonderful book, which I wrote admiringly about in these columns several years ago (see https://www.telegraphindia.com/opinion/word-and-stroke/cid/1446640). But since my name is not Gideon Haigh, I have stuck to the cliché and spun out of a photo only slightly more than a thousand words. All that you have read so far was written before I had read Ashwin’s memoir. Now that I have done so, I can confirm that at least one passage confirms my analysis of why the book carries the cover it does. The passage begins: “It eventually becomes another conversation with [the bowler-turned-batter-turned- coach W.V.] Raman. I tell him what I honestly feel. Bowlers are used as blue-collar workers by batters as they wish. Why is it that a bowler apologizes to a batter in the nets if he bowls a bad ball and not the batter if he plays a bad shot?”

ramachandraguha@yahoo.in