India, as a civilization and as a nation state, is confronting the immediacy of national elections. While our editorial writers dub the elections critical and crucial, the election as an act of storytelling seems to lack an epic format. It is more anecdotal with Modi and the Opposition staging spoofs and skits like a Three Stooges movie. There is a missingness about this election which reflects an overall emptiness of our culture. A colleague hinted that it is not the mere lack of a depth of politics but a sense of an absence of myth. He argued one cannot have an idea of India when the myths of India are becoming desiccated. It is myths that create a holism of meaning and effervescence. Myths absorb the creativity of contradiction. Modernity without its accompanying myths is futile. I was thinking about his incidental remark when I suddenly discovered the depth of its insight.

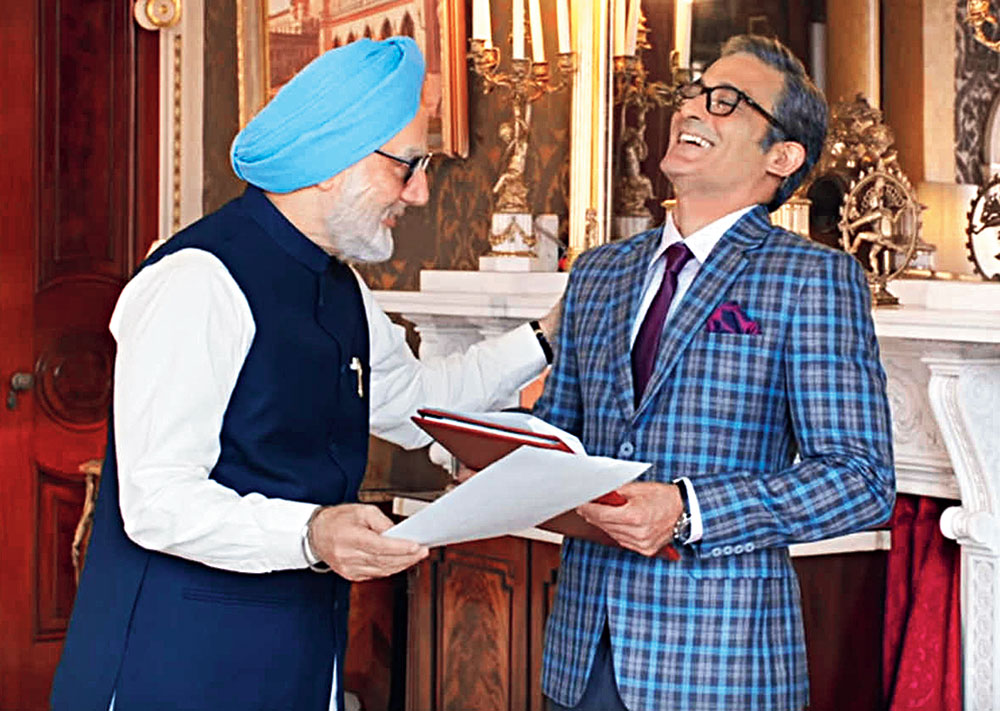

It all began in a light-hearted way when I realized that even Bollywood had lost its power of myth in its desperation to create relevance and history. The crisis of the new spate of biopics oscillating between hagiography and history is illustrative of it. Whether it is the inanity of the Accidental Prime Minister or the flat-footedness of Sanju, one gets the sense of an industry that has lost its cultural confidence. The biopic, with its urge towards the realism of biography and history, lacks a mythic magic. Our saints and heroes work best as myths because history is a myth our culture has rejected. Bollywood followed the rules of the game. It derived its appeal from enacting the myths for the future.

This bleakness of Bollywood also haunts our election scenario. India is facing an election without realizing that one sense of democracy is threatening the other. The lumpen power of majoritarian democracy, the idea of the brute power of majoritarianism, is destroying the creative plurality of Indian culture and politics. The margins, the minority, the dissentic imaginations and eccentric culture have no place in this majoritarian world, where the idea of citizenship itself has been made officially suspect. Electoral politics, by succumbing to the logic of numbers, has become tyrannical. One needs a more powerful myth of democracy to handle this crisis, and our psephologists are too inane or clerically minded to provide us with one.

The same paradox haunts the nation state and the idea of development. The nation state in its official idiom of conformity and uniformity has to confront the possibility that it is succumbing to a genocidal logic. The nation state as a concept has become a procrustean entity with a limited and totalitarian script, while nationalism provides for a dialogue of diversity. Part of the reason for this is that our current regime has lost its embeddedness in the variety of civilizations. Rejecting the variety of models and metaphors available in the civilizational discourse, our nation state has been embalmed as a 19th-century text, a mimic borrowing of parochial concepts from the West which leaves us both confused and virtually paranoid.

Development, too, is full of ironies. A term which inaugurated a sense of a more inclusive world is producing a major list of castaways including tribes, nomads and peasants. Development pretends to be inclusive when it has no place for the obsolescent and the defeated. The sheer enormity of the refugee problem is something modern India does not know how to face as it tries to forget the brutal fact that India has more refugees from the projects of development than from the wars it has fought. Development is arid as a social science. It is crying out for a myth, an idea beyond the inanity of Davos.

Sadly, if development has produced the banality of genocidal economics, science, too, has lost its sense of play, of ideal curiosity and the excitement of exploration. The way the current regime has transformed a playful science into a dismal science by over-prioritizing technology over science is one of its great acts of cultural emasculation. The dullness of our science is captured not merely in official ideological statements but in our preferences for government-driven science over the plural pursuit of an autonomously driven science. The old adage that he who pays the piper calls the tune does not quite work here, because the scientific tune is too official and limited. Instead of a variety of symphonies, we merely confront the official band playing out the scores of uniformity and banality. Science walks around in a corset when it should respond like a costume ball of ideas.

The ideas of development, too, have lost mythic power. Even the sense of new millennium indicators does not quite add a sense of desire and fantasy to development. It seems, too, to have lost the mythic power of language, a polysemy, a plurality which policing of language destroys. Myth needs a return to the imagination, a sense of gods, a sense of the impossible and improbable, an idea of sacrament which modern politics is losing today. A project on indicators or ranking hardly captures the myth of science or the creative power of a university. The storyteller, the myth-maker, get lost in the primacy of the accountant. One needs a return to folklore, to legend not as quotations and proverbs but as lived worlds. Our official concepts shun such a possibility.

When one looks at the tragic fate of words as life worlds, whether it is democracy, nation state, science or development, we realize that as words, they have lost their sense of magic and myth. Words and concepts which operate purely in secular terms become arid and banal.

All the propaganda built around them lacks the authenticity of storytelling. Not one of these concepts can generate the anticipation, the expectations, that accompany the beginning of the story, ‘Once there was...’

A failure of language is symptomatic of a deeper demise of the mythical. We can cite stories from the Mahabharata or the Odyssey but the references are limp. Our concepts lack the power of myth and the storyteller has become a declining species.

This failure is something that marks the regime and its sense of performativeness. Modi’s attempt to invoke plastic surgery as an example of ancient science confuses science as logos with myth. The attempt of Mohan Bhagwat to recreate the power of the Parliament of Religions reproduces this same failure. Bhagwat sounds like a weak liberal than the prophetic persona that Vivekananda was. The regime’s attempt, along with its cohorts, to use a weak Bollywood to bolster itself cinematically, points in the same direction.

In fact, the best example of such a failure is the way we commemorated the 150th anniversary of the Mahatma. He was reduced to mothballs and mnemonics, to a Munnabhai-like quiz, but the grandeur of his vision, his crusade, were lost in modern India. The banalization of Gandhi spelt the destruction of the Gandhian myth. One has to realize that this is a problem which goes beyond Left and Right. It demands a return to cosmology, to new metaphors, to storytelling, to dreams of a new world.

It also reveals that the world of brands is only a poor substitute for myths. India needs a sense of the mythical to survive. This is the challenge that almost every event is raising today. The sadness is that there is no storyteller left to capture such a loss, to reinvent the magic of an opening line, that claims ‘once there was... ’ as the beginning of a new world of alternatives and possibilities.

The author is an academic associated with Compost Heap, a network pursuing alternative imaginations