Bengal and the United Provinces, arguably, were the two most important sites of India’s freedom struggle against the British raj. The national movement, to be sure, spread far and wide across the country and leaders arose from practically every province in the land. Yet, the roles played by Bengal and the United Provinces were particularly noteworthy.

Since Bengal became the seat of British power after the Battle of Plassey, it was the first to be directly influenced by the raj and also the first to challenge colonial rule. Macaulay’s famous Minute advocating the teaching of European literature and science amongst the natives of India (“we must at present do our best to form a class who may be interpreters between us and the millions whom we govern: a class of persons, Indian in blood and colour, but English in taste, in opinions, in morals, and in intellect”) was first and most zealously implemented in Bengal.

Acquaintance with the English language and European thought did not just spawn generations of ‘babus’ and ‘brown sahibs’; it also stoked the desire for reform, revolution and freedom. Over the years, Bengal gave birth to both the “moderate” and “extremist” streams of the national movement — the first president of the Indian National Congress hailed from Bengal, and so did the first ‘revolutionaries’ who formed secret societies and advocated armed rebellion to overthrow British rule. The waves of ‘revolutionary terrorism’ that shook Bengal in the first three decades of the last century may not have had the sweep and depth of the Mahatma Gandhi-led non-violent satyagraha, but it did make Bengal much more hospitable to the romance of ‘radical’ politics. Subhas Chandra Bose was a bigger idol than Gandhi long before he became a death-defying legend; and communism — of varying hues — found more adherents here than in almost any other part of the country.

The United Provinces did not have Bengal’s head start, but it became the centre stage of the national movement under the Congress. Allahabad University was the alma mater of innumerable freedom fighters and Motilal Nehru’s mansions — Swaraj Bhavan and Anand Bhavan — the unofficial headquarters of the later phases of the freedom struggle. Leaders apart, the province also provided mass support to the movements against the raj — be it the Non-Cooperation Movement of 1920-22 that Gandhi abruptly called off after the violence in Chauri Chaura in eastern UP, the Civil Disobedience Movement in the early 1930s and the Quit India Movement of 1942.

One reason, perhaps, that made both Bengal and the United Provinces so important was demography. Undivided Bengal was the most populous province in British India. UP came next. No political party or movement could ignore them. And politics, it was felt, runs in the blood of the people of both states.

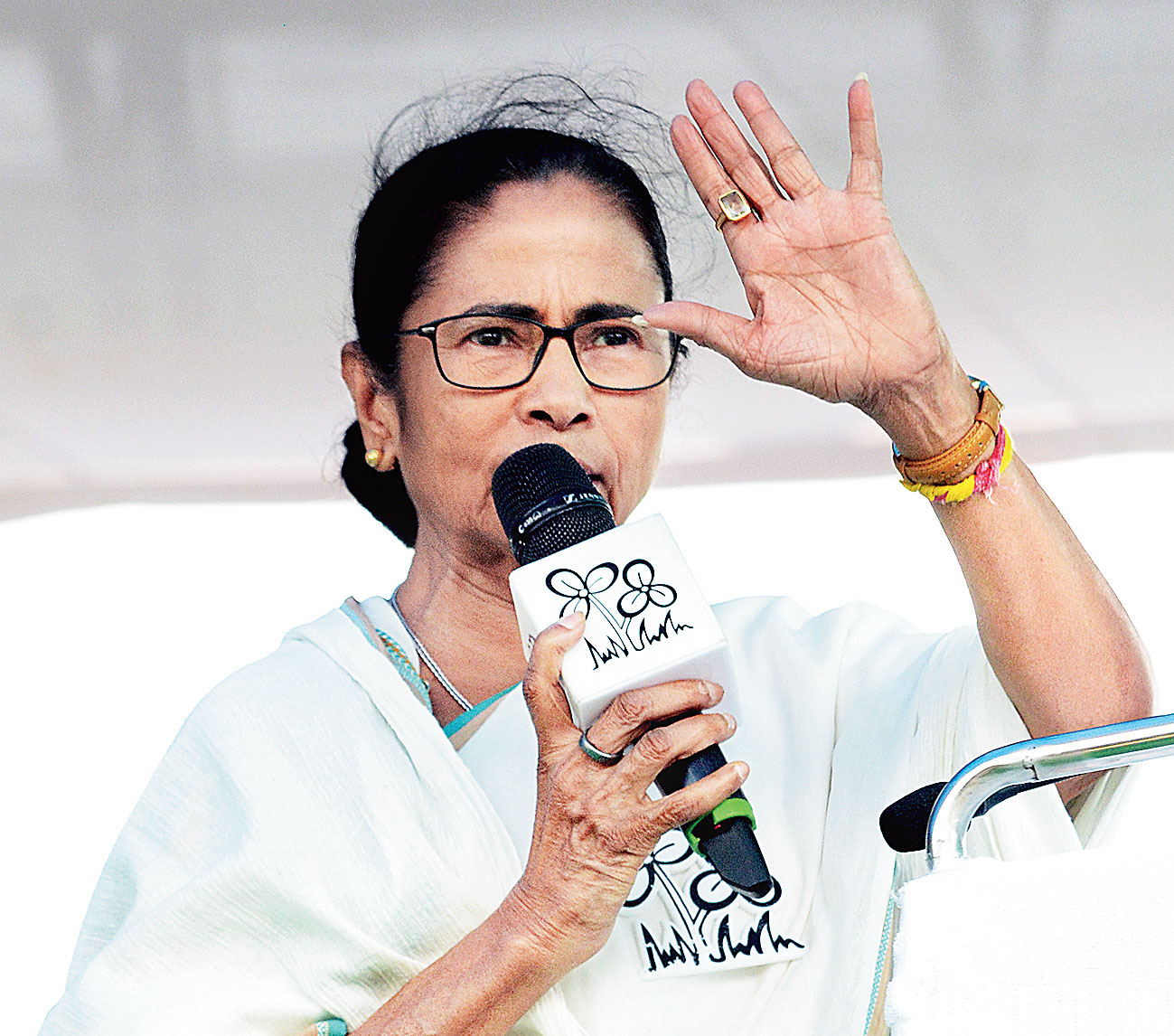

After the rigid grid formed by decades of Left rule was broken by Mamata Banerjee, the state’s politics has become fluid and volatile, allowing new forces — tapping old Partition-era paranoia — an entry. The Telegraph picture

In Bengal, where the Left took roots, street protests and class-based struggles became the norm. After the United Provinces became Uttar Pradesh post-independence, it also became a site of political and social ferment. During the freedom struggle, many streams co-existed within the Congress fold. After 1947, the streams gradually made their separate presence felt — with leaders such as Acharya Narendra Dev, Ram Manohar Lohia and Charan Singh leaving the Congress and challenging its hegemony. These leaders and their successors based their movements on caste identity which has remained central to the politics of the state.

While Bengal and the United Provinces played complementary roles during the freedom struggle, West Bengal and Uttar Pradesh followed very different trajectories and were seldom associated together after independence.

But history has come full circle today. As we await the results of India’s 17th general elections with bated breath, every discussion revolves round the role Bengal and UP will play. The Bharatiya Janata Party’s hope of returning to power with Narendra Modi at the helm depends a great deal on the results from these two states.

Uttar Pradesh, with 80 Lok Sabha seats, has always been electorally important. But for the BJP it was absolutely crucial. Without the 71 seats it won in UP (plus two won by an ally), Narendra Modi would not have led the BJP to absolute victory in 2014. Of course, the BJP managed to do very well in other states of north and west India: it made a clean sweep in Gujarat, Rajasthan, Delhi, Uttarakhand, Himachal Pradesh, and won nearly all seats in Madhya Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, Haryana and Jharkhand. It also fared well in Bihar and Maharashtra.

It might seem odd, therefore, that the BJP is so fixated on UP and Bengal when there are so many other bastions to worry about. The reason is that the BJP leadership is far less sure of the efficacy of the “Modi wave” in UP than it is in other states. In most of north and west India, the BJP is in direct contest with the Congress. Although the Congress wrested Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh and Chhattisgarh from the BJP in the assembly elections last December, the BJP thinks it will face only minor losses in the Lok Sabha elections this time. The Congress’s counter-narrative about jobs and farm distress is not strong enough to erode Modi’s popularity quite yet, it contends.

But UP is different. In this heartland state, it is not the Congress but the combined might of the Samajwadi Party and Bahujan Samaj Party (with the added force of the Rashtriya Lok Dal) that poses a real threat to the BJP. From past experience, the BJP knows that its communally polarizing politics of Hindutva has been challenged most effectively not by secular liberals but by caste-consciousness. The SP, representing the Other Backward Classes and the BSP, as the most formidable party of the Dalits, had come together in 1993 to prevent the BJP from forming the government in UP. The SP and BSP had a bitter falling out — but each remained a significant force in UP politics. In 2007, the BSP led by Mayawati swept the state elections; in 2012, the SP under Akhilesh Yadav did the same.

In the 2014 Lok Sabha elections, and in the 2017 assembly polls, the BJP did phenomenally well in UP because of the sharp division in the anti-BJP votes. The BJP also managed to make inroads into the broader bases of its two principal rivals — weaning away the non-Jatav Dalits from the BSP, and the non-Yadav OBCs from the SP. It hopes to repeat that again. But even with a broader caste coalition, the coming together of the Yadavs and the Jatavs (and a section of the Jats owing allegiance to the RLD), could cost the BJP many seats.

It is not just about arithmetic. The support bases of the SP and BSP have been kept out of the power structure by the Yogi Adityanath regime in Lucknow. Those who have once tasted power are that much more bitter at losing it — and more keen to regain it.

The BJP is hopeful that Modi’s ‘chemistry’ will override this disaffection for now — and the party will still manage a decent tally from UP. But even if it manages to win half the seats in the state, it will still be a net loss of more than 30 seats from its 2014 tally.

This is where Bengal comes in. While the BJP’s main task in north and west India has been to defend its fortress, it has gone for a no-holds-barred offensive in the east. Ever since the 2014 results, the BJP has targeted the eastern states and, to a lesser extent, the south. It tasted success in the east — winning assembly elections in Assam and Tripura, making new allies in the rest of the Northeast, and making inroads into local bodies in Odisha.

But West Bengal is its prime target — not least because the state has the third largest number of Lok Sabha seats (after UP and Maharashtra). Politically, too, Bengal is fertile territory. After the rigid grid formed by decades of Left rule was broken by Mamata Banerjee, the state’s politics has become fluid and volatile, allowing new forces — tapping old Partition-era paranoia — an entry. Besides, given the seeming inability of the Left and the Congress to take on the Trinamul Congress, the BJP reckons it can be the beneficiary of the anti-Mamata vote. The elections in Bengal are more a referendum on Mamata than on Modi, it believes, hoping to make up in Bengal (with a bit of help from Odisha) what it loses in UP.

The two states have been yoked together in the BJP’s scheme and how it fares in one or both could hold the key to Narendra Modi’s fortunes in the elections of 2019.