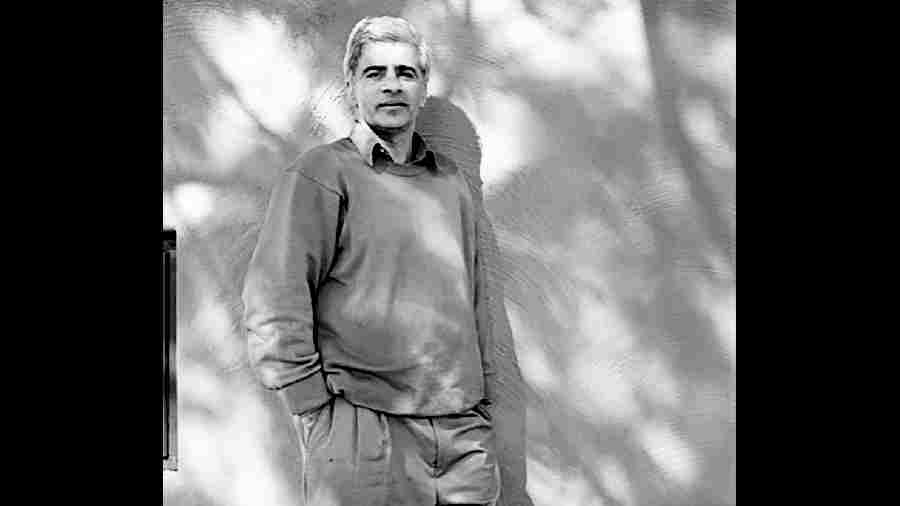

Even in a generation of exceptionally powerful artists, Vivan Sundaram stands in a different place from his co-artists. To start with painting terms that are now archaic, someone could argue about things such as original pictorial language, draughtsmanship and skillful brushwork, the mastery of colour or compositional ambition, and they could find that some of Vivan’s contemporaries were or are ‘better’ than him in one or more of these categories. I myself would take Vivan’s earlier work and argue back that he was a fantastically rewarding painter and maker of drawings, with skill to match the best of his cohort. However, the artist we lost on March 29 was someone who had long ago jumped over the old painterly fences and tramped into very different zones; and taking even that into account, he was someone much greater than just the sum of his works.

I first became aware of Vivan’s paintings along with the works of the other figurative-narrative painters, such as Gulammohammed Sheikh, Nalini Malani, Bhupen Khakhar, Sudhir Patwardhan and Nilima Sheikh. Coming from an immersion in the New York art world of the late 70s and early 80s, for a young art practitioner like me these newer painters offered a take on India that was fresh and original. Unlike the tired derivations of many in the generation before them, this loose group, (mostly, but not entirely, from Baroda’s M.S. University), managed to tell new and very local visual stories while incorporating and acknowledging their international influences within their pictures.

At the same time, a deeper dialogue had opened up in India between the practice of art and the areas of theory and philosophy as well as between previously silo-bound practices such as painting, photography, cinema, theatre and fiction writing. The critic and theorist, Geeta Kapur, was at the forefront of this opening up and by the mid-80s many of us began to avidly follow the Journal of Art & Ideas edited by Geeta and colleagues. At some point, we became aware of some connections: Vivan Sundaram was Amrita Sher-Gil’s nephew and married to Geeta Kapur; the gatherings of artists, writers and performers at the old Sher-Gil bungalow in Kasauli were organised by Vivan.

Coming to the beginning of the 1990s, different ruptures hit various history timelines: on a positive note, the Berlin Wall came down and with it the whole Soviet edifice; on the negative side, the Babri Masjid was destroyed, signalling the beginning of the long-term project of the piecemeal dynamiting of our secular republic; in India we got liberalisation; in the Middle East we got the first Gulf War; in the Balkans we got the first open bloody conflict in Europe since the Second World War. Vivan’s response to the Gulf War was a set of really powerful drawings on paper made with oil and engine detritus. His response to the horrendous post-Babri violence in Bombay was among the first of his installation works — a memorial to an anonymous victim of the organised butchery.

Across the next thirty years, Vivan kept producing a variety of work, but never fully went back to painting. Making a prodigious amount of work, at one level his practice became more overtly political, addressing the thickly criss-crossing issues of our times, but also putting the whole business of image and art-object making through the scanner of his intellect. Alongside this you were always aware of his political commitment to workers’ causes, to secularism and to the Left movement in general. Although never a member of the Communist Party of India (Marxist), Vivan remained closely associated with the party.

As you got to know Vivan you also began to notice the difference between him and some of the ‘star’ artists in the Indian milieu — while he was aware of the value and power of his work, there was no trace of any pompous self-regard that you so often found in other artists both older and younger than him; he was always curious and open to other people’s work; even with fraying health, Geeta and he would come to every exhibition and a wide variety of events in Delhi; whereas others needed or revelled in their isolations, Vivan often sought out collaborations or created situations where his work became a frame or a large tent or a co-exhibition for the work of other, often far less-known artists. Over the last few years, Vivan, his sister, Navina (who passed away last year), and their close associates set up the Sher-Gil Sundaram Arts Foundation to support the arts and generate dialogue. Even while totally focused on his work, Vivan Sundaram was that rare creature who could pull back and see himself as part of a community, as part of a collective movement, as part of an ever-flowing history of activism and creativity.

“In the dark times/ will there also be singing?” asks Bertolt Brecht, before answering the question himself, “[T]here will also be singing./ About the dark times.” From early in his career, Vivan Sundaram never shied away from singing visually about the darkness of the times through which he was living. Along the way, he enthusiastically joined voice with others, those of us who were also trying to sing in our different voices and pitches. I know from the times I met him over the last few years that — like so many of us — he was looking forward to one day waking up in brighter times and being able to sing about other things. It is a huge sadness that he physically won’t be there to see the end of the current tyranny, but those of us who are there on the day the darkness is defeated will remember him with warmth and gratitude and remember how much he helped us reach that place.