Supreme Courts the world over have ebbs and then moments when redemption begins and usually those also converge with wider changes in the political and social environment. The Supreme Court of the United States of America had, in the final decades of the 19th century and the early decades of the 20th, constitutionally enforced segregation and contributed to the rolling back of the social and political progress that had followed the civil war and the abolition of slavery. A redemptive process began only in the 1950s when its rulings on civil rights and against discrimination corrected earlier pronouncements and, by establishing new baselines, reinforced a wider social and economic change that was underway in the US with the civil rights movement. In India we have our own experience of the judiciary during the Emergency, but thereafter the higher judiciary has emerged as the ultimate safeguard of human and constitutional rights.

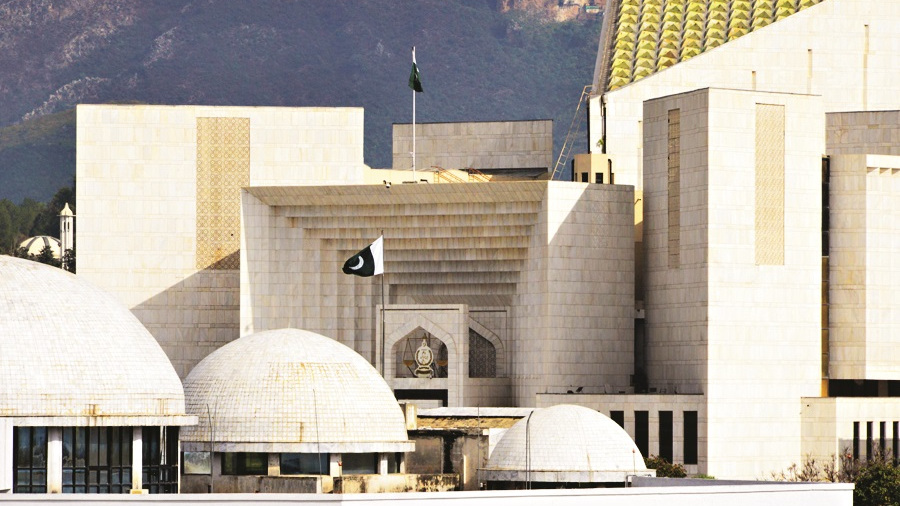

The judiciary in Pakistan has always had a greater burden of credibility than elsewhere. In large part this is for reasons that stretch back to the country’s early years. Required to pronounce on the legality of bureaucratic erosion of representative bodies and military coups in the 1950s, the Supreme Court of Pakistan resorted to dubious legalities and validated the usurpation of constitutional authority. Another milestone was the execution of Zulfikar Ali Bhutto in 1979 which many in Pakistan today would readily accept was no more than a judicial murder.

Some three decades later, the picture appeared to have changed with a protest led by lawyers and judges over the dismissal of a sitting Chief Justice in 2007. The dust finally settled with a military dictator forced out. It was felt that Pakistan’s judiciary may have turned the corner and this was also part of a larger change of civilian institutions and political parties asserting themselves and ring fencing the future role of the military.

But a decade later, these hopes were belied. Over 2017, a series of controversial interventions and pronouncements by the Supreme Court of Pakistan put an end to the tenure of the prime minister, Nawaz Sharif. Whatever may have been his errors of omission and commission, the fact is that his ouster flowed from the friction in the interface his government had with Pakistan’s army. The Supreme Court’s interventions were a setback for Pakistan’s political process in different ways. Two in particular are worth recalling. First, a premature termination of Nawaz Sharif’s tenure as prime minister meant that Pakistan’s historical record of not having a single prime minister who completed a full tenure continued without a break. Second, the perception that the higher judiciary had acted in concert with the army to change the prime minister gained credence.

This summary, treading over past issues, is on account of their surfacing again by way of the prominent case relating to a judge of the Supreme Court, Qazi Faez Isa. He is about as close as one will get to the original blue blood of Pakistan. His father, one of the first barristers of Balochistan, was a close associate of M.A. Jinnah and helped establish the Muslim League in Balochistan. Justice Isa was appointed as a judge of the Supreme Court in 2014 and, as things stand, will become Chief Justice of Pakistan in September 2023 and will remain so for a little over a year. 2023 is incidentally an election year in Pakistan as the tenure of the government of the incumbent prime minister, Imran Khan, will come to an end.

In 2018, Justice Isa in the Supreme Court heard a suo motu case relating to what was called the “Faizabad sit-in” — a protest in November 2017 led by a religious front, the Tehreek-e-Labbaik Pakistan, against the government that demanded the resignation of the law minister. The Supreme Court took up the case as the 20-day-long protest severely disrupted the capital’s functioning. Politically, the disruption was another nail in the then government’s coffin — Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif had been forced out just a few months earlier — and the protests left it further beleaguered and bleeding. Many speculated, perhaps with some merit, that this was a replay of what had happened earlier in Pakistan with the military moving to re-engineer the political architecture.

The case was heard over 2018 and the judgment pronounced by a two-judge bench in February 2019. This was long after the protests and with a new government led by Imran Khan in power. It was in that sense an ‘academic’ judgment. Nevertheless, the verdict — and it was authored by Justice Isa — made critical remarks about the role of the intelligence agencies — in particular the Inter-Services Intelligence — in the Faizabad ‘sit-in’. That in itself endowed Justice Isa with a certain notoriety on the perennial and vexed question of the role of Pakistan’s army in the larger polity. The judgment, after going into various issues of the right to protest, reasonable limitations to it, the coverage of the protesters in the media and the handling of these protests by the government, went on to state: “The perception that ISI may be involved in or interferes with matters with which an intelligence agency should not be concerned with, including politics, therefore was not put to rest.” It made other references, including that perceptions of the involvement of the ISI “gained traction” when the sit-in participants received cash handouts from men in uniform. Amongst the conclusions of the judgment was that intelligence agencies “must not exceed their respective mandates”.

The judgment obviously made headlines and not just in Pakistan. The ISI protested and so did a whole phalanx of army fronts. A number of review petitions were filed including petitions by the ministry of defence and the ISI. What was of more significance was that reports started circulating soon after the judgment about possible moves against corrupt judges, and soon thereafter, confirmation came that the government had, in fact, moved against Justice Isa and two other judges for not disclosing the fact that they (or, in the case of Justice Isa, their family members) owned foreign properties. Meanwhile, Justice Isa also approached the Supreme Court challenging the reference against him. This case went through various phases but a full bench decision of the Supreme Court in late April this year ended all the proceedings against the judge. Thereafter the government’s efforts to have the decision reviewed have been turned down.

For many in Pakistan, this appeared as a redemptive moment for its higher judiciary. Legalities apart, the final decision even evoked parallels with 2007 when a full bench of the Supreme Court had reinstated the deposed Chief Justice. Whether the Justice Isa matter is finally closed now remains to be seen. This summer has, however, been a hectic one in Pakistan when Opposition parties, media professionals and judges have challenged prevailing totalizing narratives that the establishment or the army controls all in Pakistan. The wider context is a pandemic and a faltering economy, but a ceasefire on the line of control with India that has held for over 100 days adds some positive content. These contradictory trends may well suggest that some structural change is again underway in Pakistan, but then a single swallow also does not make a summer.

T.C.A. Raghavan is a former high commissioner to Pakistan and is currently Director General, Indian Council of World Affairs