You are 21 years old, going on 22. Three years ago, and a bit, you finished your final board exams, with a result that was neither terribly exciting, nor too disappointing, and then you got admission to a college you were reasonably happy with. So there you were, wearing your most stylish outfit, going for your first day of class in a new, and unfamiliar, institution, surrounded with other 18-year-olds who hid their shyness under a veneer of jaded sophistication. You noticed that some of your new classmates had better clothes, or smarter phones, than you, and maybe you were made fun of for not knowing what was “in” and what was not. But, like the infinitely adaptable being that you are, somehow, and somewhat to your own surprise, you began to fit in. The days passed in a whirl of unfamiliar, and occasionally, slightly disorienting, activities. You made friends, began to do things you’d never dared to when in school (writing poetry, acting in skits, attending political demonstrations), finally gathered up the courage to ask that rather attractive classmate out for a cup of coffee only to discover he/she already had a “significant other”, and wore your heartbreak with what you hoped was Buddha-like stoicism. Before you knew it, the class tests and assignments started, and soon enough you sat for your first-ever semester exams. Your results, when you looked them up, came as a bit of a shock — surely you hadn’t messed things up so badly? Whatever happened to those excellent scores on that laminated +2 marksheet? Perhaps your parents chided you, perhaps not; maybe your new best friend put a consoling arm around your shoulder in the canteen, and you felt oddly comforted. Or maybe not. But, never mind, there were several more semesters to come, and you resolved to try harder, do better, and prove the naysayers wrong. And, wonder of wonders, you did. Your second semester results were significantly better than the first, and by the time you were in the third semester, you had gotten into the swing of things — casually balancing studies with other, usually more exciting, activities, with an ease that sometimes made you feel rather pleased with yourself.

A couple of years later, as you started your final semester, the old doubts and uncertainties began to resurface. What next? Should I try for admission to that premier institution my folks had set their hearts on from when I was so high? Or should I just stay put here? Maybe I should join some more “market friendly” course? Get a diploma in computers, or a foreign language, or try to intern for that firm that doesn’t pay well but will look good on my still-under-preparation curriculum vitae? Maybe I should take a gap year and try to make a career in theatre? Choices. Choices.

In your final semester, busy as you were with hoping to improve your cumulative grade point average, and thinking of what you’d like to do next with your life, you paid little attention to news about some kind of weird virus that had apparently passed from bats (!) to humans, in some province in China, and scarcely glanced at the small news items that kept popping up about people falling ill because of some kind of ‘flu. But, sometime around the end of February, the news headlines became bigger, something called SARS-CoV-2 kept appearing on television channels and your Facebook page and, before you knew it, halfway through March, your college/university was abruptly shut down.

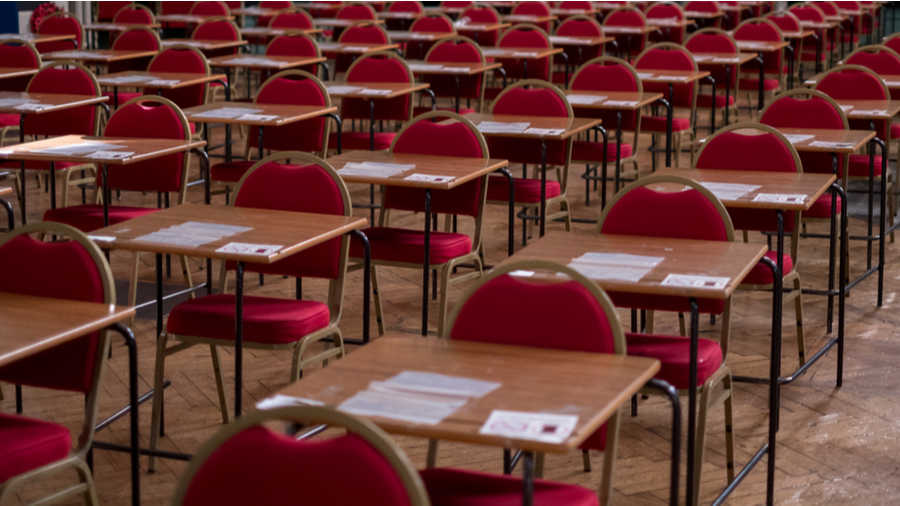

You weren’t too worried, and your folks assured you that things would get back to normal in no time at all. Maybe you kept going to college to hang around with friends, maybe you watched an illegally-downloaded print of Contagion — this is just so much Hollywood hyperbole, you thought. Science has progressed so much, we’ll have this thing beaten in a few weeks, at worst. But you also resolved to spend some more time on that particular text that you’d failed to pay attention to in class, busy as you were with the last of the college fests, and, just to be on the safe side, you called up the class topper to ask when you could go over to discuss it with her. But, scarcely a week later, the entire country went into something called a “lockdown” — no more going over to the topper’s home, no more gossip with your mates. By now, you were getting worried, so you did what so many of your friends were doing: you began to calculate how much of your course you’d completed, been tested on, and received grades for. This was more familiar ground. You calculated that you’d already been assessed on more than 83 per cent of your course (actually, you reasoned, more like 87 per cent since you’d already completed several assignments this semester); your friends who were doing four-year, eight-semester, programmes, had been assessed on more than 90 per cent of their course. Even as the pandemic began to spread, you reasoned that your teachers would find a way to ensure that you completed your studies, and emerged with a degree. At the end of April, you felt vindicated. The University Grants Commission brought out a set of guidelines that allowed universities to assess students using a combination of internal evaluations and previous semesters’ scores, and your parents were relieved that you wouldn’t have to sit for examinations in those crowded halls, where social distancing was impossible to maintain. So you began to dream of a future once again; a more uncertain one, to be sure, but at least you’d have a degree to face it with. And then, with a suddenness that seemed to mimic the arrival of the novel coronavirus, earlier this month you heard that the same UGC was now asserting that “Final Term Examinations should be compulsorily conducted”, “to safeguard the larger interests of students” since “performance in examinations brings in scholarships and awards and translates into better job placement” and would give students “more confidence and satisfaction” and “also ensure merit and lifelong credibility”.

Today, as you hear of states challenging the UGC’s mandate, and cases being filed in the highest court of the land, you cannot help but recall the inspirational speech the head of your institution had delivered, the day you’d stepped into the place that now feels like your second home. “No longer will you be assessed on the basis of your performance on a single examination. The semester system is student-centric, flexible, and allows for an ongoing evaluation of your performance. Not a one-off assessment of your abilities, but a process of continuous assessment — by us, but most importantly, by yourselves.”

You think to yourself, but I have been assessed, I have taken examinations, I’ve done assignments, term papers, student seminars; I know how well or badly I’ve done, I have a pretty fair idea of what my final CGPA will be. What makes these final-semester examinations so important, that they are worth risking our lives for? What about our teachers’, and our family members’, well-being? Plunged into renewed despair, you ask your friends, and your teachers, and your elders, but no one seems to know the answer.

The author is professor of Comparative Literature, Jadavpur University, and has been working as a volunteer for a rural development NGO for the last 30 years.