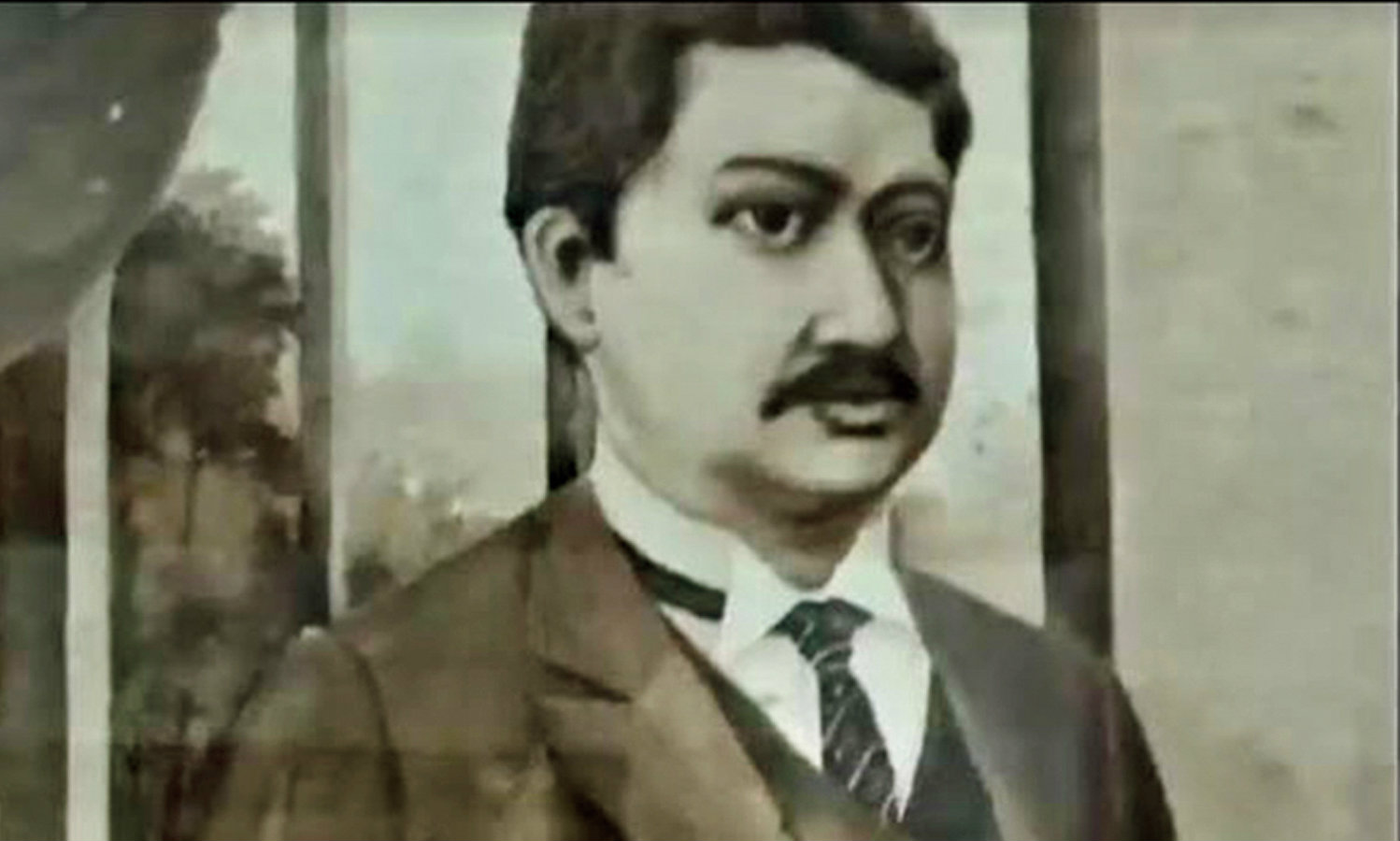

If any pernickety Assamese critically scrutinizes the background of some of the names in that ultimate bible of acceptance, the National Register of Citizens, he might raise an eyebrow over one of Assam’s greatest sons. “If Anundoram Borooah is not an Englishman,” said a contemporary, “then he is definitely a Bengali.” Plans for a condolence meeting in Jorhat when he died in Calcutta on January 19, 1889 fell through because some locals complained the man who elegantly blended the 19th century’s civilized ideal of faithful service to the British Crown with cultural patriotism was more Bengali than Assamese.

Amalesh Dasgupta’s evocative film, Anundoram Borooah: A Forerunner of Modern Assam, screened recently by the Indian Council for Cultural Relations, involved indefatigable research. Luckily, he succeeded in making some dent in Presidency University’s obdurate bureaucracy which is more inclined to stonewall inquiries. But the film’s real significance is that it was made at all. The Indian Civil Service isn’t fashionable. As Clive Dewey observed, “[H]istory is written by the victors, so decolonization wiped the ICS off the agenda.” Charles Bayly’s view that instead of being called “collaborators”, Indian officials should “be taken seriously as participants in the discourse of Indian patriotisms” has few takers. The late Chitra Deb might even have gloated that the film vindicates her contention that “the British were emulated by the ‘Desi Sahibs’, most of whom were Indian Civil Service officers” since it shows Anundoram sartorially an anglophile like his predecessors, Behari Lal Gupta, Romesh Chunder Dutt and Surendranath Banerjea.

Each had a claim to fame. Gupta’s note on judicial discrimination inspired the Ilbert bill. Dutt argued famine economics with Curzon. Banerjea was the unforgettable “Surrender Not”. Apart from being the first Indian in charge of a district, Anundoram sought India’s undying soul in Sanskrit and the ancient classics. Dasgupta highlights his classical erudition, explaining he took leave to research monumental works like the English-Sanskrit Dictionary or Ancient Geography of India. It was his hope that widespread and inexpensive Sanskrit education would enable Indians to “care more for their home literature than they now do for Shakespeare and Bacon, Addison and Johnson.” Through Gupta, he bought a house in Berhampore from Rani Swarnamoyee and set up the Arunaday Yantra press. Significantly, Arunaday was the name of Assam’s first newspaper run by Baptist missionaries from 1846 to 1888.

As a 14-year-old schoolboy in Assam, Anundoram was already dedicated to Sanskrit studies and could recite by heart Amarasimha’s Sanskrit thesaurus, Amarakosha. A series of scholarships facilitated his progress. One took him to Calcutta’s Presidency College where he was a student, like Gupta and Dutt, of Gooroodas Banerjee, who praised them as “the flowers of the Indian Civil Service” and men “who left behind them indelible impressions on the judicial and executive administration of the country”. Two other scholarships guaranteeing an annual £300 enabled Anundoram to go to England in May 1869 and qualify for both the ICS and Bar. On his return in September 1872 he faced the challenge that had also confronted Gupta: his father wanted him to perform a prayaschitta ceremony. Like Gupta, he refused without any lasting bad blood, so far as one can tell.

Dutt and Banerjea were spared this dilemma since their fathers were already dead.

Was Anundoram the fifth or sixth Indian Civilian? Satyendranath Tagore’s breach of the white fortress in 1864 was perceived as “the thin end of the wedge that presaged shoals of natives bullying and controlling Englishmen”. Then came the trio mentioned earlier and Sripad Babaji Thakur, “unchristian Civilians… from depraved and idolatrous backgrounds”. That makes Anundoram the sixth. But the talented if wayward Thakur lost a year over the age controversy and joined the service with Anundoram who is regarded as his senior because he obtained higher marks, according to his biographer, Mukunda Madhava Sharma.

It would have been remarkable if Anundoram did not have problems with the authorities. The film tells us that if Surendranath was over age (or appeared to be so), Anundoram was under age. Two years after his return, Sibsagar’s European police chief seated Anundoram and Zalnur Ali Ahmed, the civil surgeon whose grandson was Fakhruddin Ali Ahmed, at a separate table at a dinner for the visiting chief commissioner. Around then, Anundoram had to stop his Assamese guests from jumping up and offering their chairs to a couple of Europeans who had dropped in. The government’s attempt to restrict the language exams an Indian Civilian could take was more serious. A senior British official grumbled that studies and travel to examination centres took up “three or four months out of each year” and earned a Civilian “between Rs 20,000 and Rs 25,000 as reward”. He felt even more aggrieved when some Indians won prize money for tests in languages they were accused of “learning more or less directly since early childhood”. That couldn’t be said of Gupta’s scholarship in Sanskrit and Persian; moreover, he needed the money to repay Dutt who had financed his trip to England. Anundoram’s prizes were also resented but attempts to discipline the brilliant young Assamese were abandoned when a European Civilian flatly refused to give up his own prize-winning feats.

A more serious dispute arose over Clause 9 — compulsory contributions to the widows and orphans fund so that wives and children were not destitute — of the Covenant all Civilians signed. Suspecting Indians of conniving to saddle the exchequer with dozens of wives and hundreds of offspring, London had been trying to wriggle out of Clause 9 ever since Satyendranath’s entry. A surreptitious attempt was made four months into Gupta’s first posting by asking him to return the Covenant “for inspection”. Gupta retorted outraged, “I had not the remotest idea that simply on the ground of my being a native of India I was not to be considered fully eligible to all the rights and privileges of the civil service just as successful candidates of other nationalities.” He probably knew of the bias revealed in Bernard Shaw’s later crack about Rabindranath Tagore — “Old Bluebeard, how many wives has he got, I wonder!”

C.A. Buckland, former 24 Parganas commissioner and Gupta’s boss, told a meeting in London during the Ilbert bill controversy, “These Natives are really very clever fellows in some respects. Most of you have heard of the Civil Funds, and it became necessary to ask those gentlemen to undertake to practise monogamy... we had to bind down these Native Civilians to practise monogamy so that they might not swamp our funds with any number of wives and an indefinite number of children...” It was hinted that except for widows and widowers, Indians procreated relentlessly. Although determined not to surrender a legitimate entitlement because of race prejudice, Anundoram must have alarmed the British even more by pointing out that more and more widows were taking advantage of the Special Marriage Act of 1872 permitting remarriage. “Thanks to the labours of Pandit Ishar Chandra Vidyasagar, it is no longer true that ‘widowhood’ is perpetual,” he said, mentioning an Assam officer who had married a colleague’s widow. Far from being a child widow, she was at least twenty-five.

Anundoram himself died a bachelor in Taraknath Palit’s house across the road from the flat where I live. He was only 39. As mourners crowded the house, one of them lifted the shroud to declare “Here lies the glory of Bengal in his eternal sleep.” A young Assamese contradicted him, “He is not the glory of Bengal. He is the glory of Assam lying in eternal sleep.” An elderly Bengali intervened more accurately to say, “No, here is a great man, a glory of India, lying in his eternal sleep.” It was a fitting epitaph. The film’s message is that those early Civilians were also the first Indians.