Amiya Kumar Bagchi, the doyen among Indian economists who passed away on November 28, was ‘Amiyada’ for me not just out of courtesy; he was really like a ‘dada’, an elder brother, affectionate and full of wise counsel. We had first met during Christmas in 1967. My wife and I were graduate students at Oxford and Amiyada was a member of the economics faculty of Cambridge and a fellow of Jesus College. Our friend, Sajni Mukherji (née Kripalani), who later became professor of English at Jawaharlal Nehru University and Jadavpur University, was doing a temporary vacation job in Cambridge and staying with the Bagchis; she had asked us to come over there during Christmas. We had originally demurred but the total shutdown for those three days (not even a cat on the streets) forced us to accept her invitation and tax the Bagchis’ hospitality.

Amiyada gave me two of his papers to read, both later incorporated in his book, Private Investment in India 1900-1939. He had written a doctoral thesis using Game Theory, which Brian Reddaway, a very practical and down-to-earth economist, later to occupy the Marshall Chair at Cambridge, advised him to modify and focus instead on the bit of economic history that the thesis had contained as a case study. Amiyada mercifully accepted Reddaway’s suggestion and the magnum opus referred to was the result. I too had started out working on the theory of optimal growth (then a favourite topic among mathematically-inclined graduate students), but reading Amiyada’s papers made me follow in his footsteps and change course. By a curious coincidence, I got the very job he had at Cambridge after he returned to India to be with his wife upon the demise of her father.

Amiyada was not really an economic historian; he was a macroeconomist working on historical and contemporary data, similar to what economists like A.C. Pigou and J.M. Keynes had occasionally done. In this sense, he was among the first modern Indian economists who shunned the distinction between theoretical and empirical work and straddled both spheres.

He was also extraordinarily imaginative. Francis Buchanan-Hamilton had been a surgeon who undertook extensive surveys in the early nineteenth century at the behest of the colonial administration. Amiyada compared his records on people’s occupations with later census data to establish definitively the fact of ‘de-industrialisation’ under colonial rule which had been flagged by the nationalist writers but had not been clinched owing to the absence of data for the earlier period.

Amiyada’s researches not only substantiated many claims of nationalist writers about the impact of colonialism (in fact, even his critics concede that his Private Investment is a classic work that deserves to be placed alongside the works of Dadabhai Naoroji, Romesh Dutt and D.R. Gadgil) but also illuminated the role of imperialism in creating the development-underdevelopment dichotomy. Starting with an article in the Economic and Political Weekly in 1972 which was a sweeping historical analysis of the world economy in the long nineteenth century, he further developed this theme in his book, The Political Economy of Underdevelopment, and finally in his magisterial work, Perilous Passage: Mankind and the Global Ascendancy of Capital. This body of work carried forward the intellectual legacy of Paul Baran’s opus, The Political Economy of Growth, and is of outstanding importance for understanding the genesis of our time.

He also wrote numerous books and articles along the way, such as a two-volume history of the State Bank of India (earlier the Imperial Bank of India); a study of East and Southeast Asian industrialisation; and a disquisition on Lenin’s theory of imperialism. Committed to Left politics, he served on the West Bengal State Planning Board as a member, and later as its vice-chairman, under the Left Front government.

Amiyada was not just a trenchant critic of neoliberalism; he was also the earliest one. The OECD had brought out a number of case studies and a summary volume in 1970 based on these case studies, critiquing the dirigiste development strategy in third world countries and preparing the intellectual ground for the introduction of neoliberalism; Amiyada wrote a devastating review of this summary volume in the Economic and Political Weekly titled “The Theory of Efficient Neo-colonialism”. His opposition to its vision never flagged.

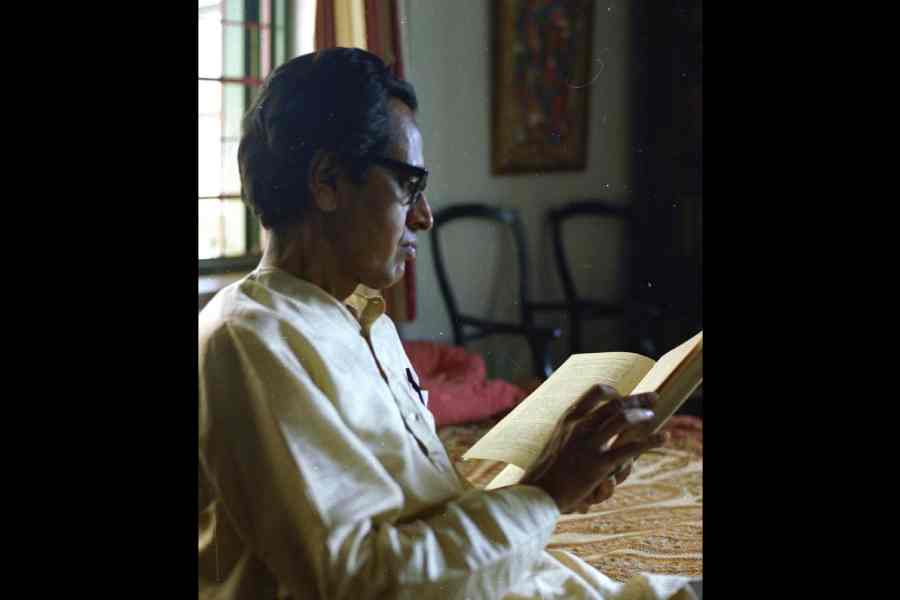

Fiercely outspoken, totally free of any guile, and generous to a fault, Amiyada had a remarkably transparent personality. Recognition naturally came his way, such as the general presidentship of the Indian History Congress, a Padma Shri, and numerous visiting professorships and honorary doctorates; but he made light of it.

Utterly loyal to Calcutta and West Bengal, he turned down professorships at the Delhi School of Economics and JNU. He would travel widely, accept invitations to speak in far corners, but always return to Calcutta where he felt culturally most at home. He taught at Presidency College, and later at the Centre for Studies in Social Sciences, Calcutta of which he became director. Later still he became the founder-director of the Institute of Development Studies, Calcutta; he was professor emeritus there until his last days. Going to Calcutta invariably meant for me spending time with Amiyada whose house was for a long while a home away from home.

The loss of his wife, Jashodhara Bagchi (Ratnadi), a very distinguished academic who had been professor of English at Jadavpur University and chairperson of the West Bengal State Women’s Commission, had been a big blow to Amiyada, leading to a curtailment of his activities in the last few years; but his commitment to a world free of exploitation had never dimmed despite his privations.

Prabhat Patnaik is Professor Emeritus, Centre for Economic Studies and Planning, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi