Narendra Modi’s attribution of Chandrayaan-3’s spectacular success “to all of humanity” was even more magnanimous than Neil Armstrong’s contested “one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind.” But here in Singapore I saw little trace of the excitement generated by the Pokhran-II nuclear tests in 1998. A local Indian, an elderly Sikh Singaporean I met by chance in a hawker centre, told me then, “I’ll never go back but a nuclear India makes my position stronger here.” Even India’s official representative felt that when Singapore’s foreign ministry summoned him, it was to deliver “only a pro forma protest” about the tests. Clearly, Singaporeans saw nuclear power as more essential for the Indian state and the future of a billion Indians than landing on the moon.

Not that the two achievements are comparable. But both prompt questions of practical application, priorities and alternative yields from similar investments of human and material resources in a land that must carefully husband both, never mind how paltry they seem against the humongous space budgets of the United States of America or the Russian Federation. India’s lowly rank (132 out of 191) in the United Nations Human Development Index makes milestones like Pokhran-II and Chandrayaan-3 especially significant. One cannot but pause to consider the difference that it might have made to all aspects of daily life if this intense cooperative effort involving hundreds if not thousands of highly-trained and dedicated personnel had been devoted to health, food production, safe water, housing, transport or primary and secondary education, and if the basic necessities of life had benefitted from the high technological skills that Indians can obviously master.

The somewhat brash appearance of the Indian Space Research Organisation’s current website with the G20 logo squatting in a telltale lotus amidst a scattering of slogans like “Azadi ka Amrit Mahotsav” and “Sabka Saath, Sabka Vikas, Sabka Vishwas, Sabka Prayas” may not fully convey the gravitas of a lineage that goes back to the 1940s. The initiatives that stalwarts like C.V. Raman, Vikram Sarabhai, Homi Bhabha and others took even before Independence enjoyed Jawaharlal Nehru’s full blessings even though — or probably because — their serious scientific purpose was untainted by any whiff of political propaganda. Nehru’s farsighted commitment to Alexander Pope’s vision that “the proper study of mankind is man” ruled out any conflict of priorities. “It is science alone that can solve the problems of hunger and poverty, of insanitation and illiteracy, of superstition and deadening custom and tradition, of vast resources running to waste, or a rich country inhabited by starving people” was how Nehru affirmed the lofty purpose of scientific endeavour. “Who indeed could afford to ignore science today?” he asked. “At every turn we have to seek its aid... The future belongs to science and those who make friends with science.”

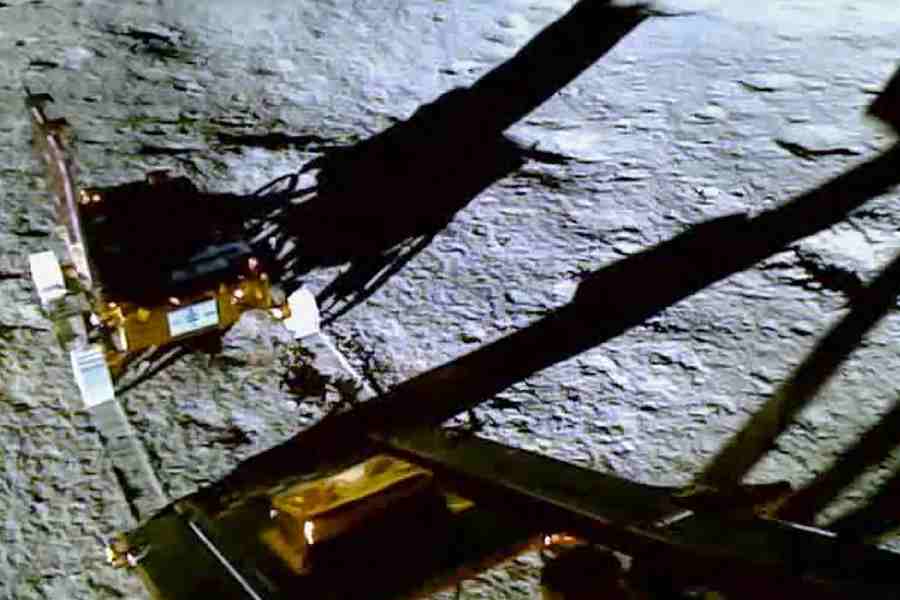

That perception made it impossible for Nehru to demean science by distorting it to fit frameworks of dogma and ignorance. He would not dream of buying the applause of illiterate multitudes by proclaiming that ‘Rama flew the first aeroplane’ or that ‘stem cell technology was known in ancient India’. Nor would his education permit him to claim that Ganesha was living proof that plastic surgery flourished in pre-historic times or trivialise the moon landing as commonplace in daily life allegedly described by Aryabhata, the sixth century astronomer and mathematician. Nehru’s own rational mind, to say nothing of his scientific training, would have told him that the fourth landing on the moon, and on an unexplored part of the lunar surface at that, could only have been accomplished through painstaking effort to master a whole new range of skills.

Sceptics there are bound to be. The claim by Sabeer Bhatia, who invented and then sold Hotmail to Microsoft, that “90 per cent of the innovation industry is copycat in India, there is nothing new they do” may even appear to hold a grain of truth when he also rails against an education system that forces children to chase marks instead of asking incisive questions. Official policy is in bondage to antediluvian ‘Make in India’ concepts, he told a Mumbai seminar, whereas a product of the modern creator economy like Tesla employs only 300-400 people. The copycat charge, which is by no means new, recalls Western allegations of reverse engineering against certain branches of India’s pharmaceutical industry. There is also evidence of the defence industry’s dependence on Western prototypes, especially in sensitive spheres. The painful years of protracted negotiations before the supposedly ‘trailblazing initiative’ to manufacture a light combat aircraft in India was at last finalised, frantic requests for Israeli mortars, ammunition and spares during the 1962 war with China, and reported appeals to Russia during the more recent Galwan stand-off for the blueprints of assault rifles hardly bear out the image of ‘Atmanirbhar Bharat’. The intriguing mystery of the $403 million, 182-metre statue, the tallest in the world, of the man whom the ruling party has adopted as its iconic spiritual leader, Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel, may provide clinching evidence of India’s lack of self-sufficiency. If the charge about the 2,000-tonne statue be true, then India’s Man of Iron is clad in some 6,500 bronze panels obligingly crafted and shipped out by the Jiangxi Tongqing Metal Handicrafts foundry to China’s arch rival in Asia which is careful to avoid belligerent rhetoric while playing footsie with a US that is desperately trying to mobilise an Asian anti-Chinese front.

Ability deficit isn’t the only reason why India cuts a lame figure in the global marketplace. Many years ago I wrote an article titled “For India, Not Indians” on a curious national complex. It was provoked by suffering a long railway journey in a first class, air-conditioned, desi-made coach of which the authorities were inordinately proud. Nursing childhood memories of the luxury of even the ordinary first class coaches of British Indian trains, I could regard the best of the new India as only a filthy slum on wheels. The old coaches were moulded and panelled in gleaming teak with deep leather cushioning. Railway sweepers kept them spotlessly clean without fuss or fanfare, and the restaurant service compared with the best hotels in the land.

The style and standards of that era could have co-existed with the dazzling age of Pokhran-II and Chandrayaan-3. One reason why they have been abandoned is that the class to which they catered no longer matters to governments whose concern is for only vote banks and the very rich. Another is that official effort and finance is channelled mainly into areas that impress international audiences. It would be wonderful if the moon landing boosts employment, encourages private investment, and fosters the growth of a domestic space-tech ecosystem. The 123 India-US agreement also generated high hopes about nuclear energy. But the chances are that just as our IITs feed various US guest-worker programmes that a California University professor dubbed “indentured servitude”, an expanded new space industry will further stimulate migration, allowing the government to wallow in the indiscriminate adulation of non-resident Indians who are more polite than Bhatia. A complaint heard here is that while the 2005 India-Singapore Comprehensive Economic Cooperation Agreement created openings for Indians in Singapore, it has not done the same in India for Singaporeans.

In the outcome, the services and facilities for India’s middle classes are getting shabbier and shoddier. When the trend first manifested itself, people joked that India was trundling to the moon on a bullock cart. No one guessed then that the crack would one day be so painfully and pathetically near the truth.