The US-Taliban agreement has inevitably drawn comparisons with previous arrangements for great power withdrawal — most notably the United States of America from Vietnam in 1973 or the Soviet withdrawal from Afghanistan in 1989. There are other, more recent, examples: the US from Iraq and Nato forces from Libya. In each case, what was common is the sense of uncertainty —even foreboding — of what is to follow.

In Afghanistan’s case, however, there is one striking element of continuity between the Soviet withdrawal of 1989 and the present US agreement with the Taliban. The Soviet withdrawal had followed the Geneva Accords of April 1988; a set of agreements signed by Pakistan and Afghanistan and guaranteed, in turn, as co-signatories by the US and the Soviet Union. The agreements laid out the principles of future bilateral relations between Pakistan and Afghanistan, such as non-intervention and non-interference in the other’s affairs, return of refugees and so on. Immediately after the signing of the agreement, explanatory statements were issued by Pakistan and the US, clarifying that their signature did not imply recognition of the “regime in Kabul” that had also signed the agreement. The US statement, for instance, reads: “By acting as a guarantor of the settlement, the United States does not intend to imply in any respect recognition of the present regime in Kabul as the lawful government of Afghanistan.”

It would be too easy to blame this factor on the collapse of the agreement and its inability to prevent the civil war that destroyed Afghanistan subsequently. The fact is that the wider geopolitics that supported the delicate compromise of the Geneva Accords changed with the extinction of the Soviet Union and the end of the Cold War.

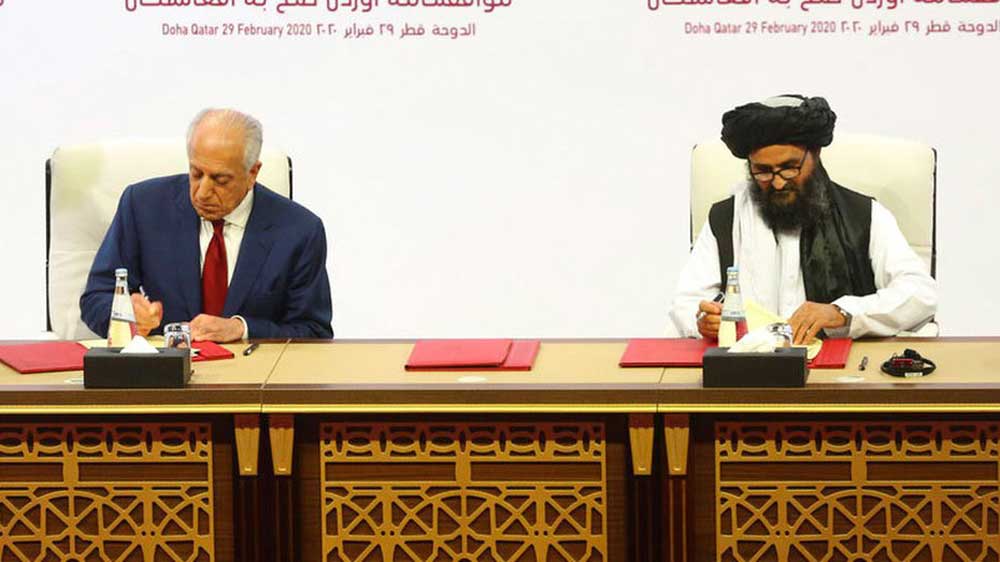

Nevertheless, the non-recognition element does come to mind in the context of the February 29 peace agreement with the Taliban that provides for US troop withdrawal from Afghanistan. The agreement is between the US and the ‘Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan’ or the Taliban but each reference to the latter in the text has the clarification that “the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan is not recognized by the United States as a state”.

Much like the 1988 Geneva agreements, this is also a delicate compromise and it remains an open question whether and how the contradiction between the ‘Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan’, as the Taliban call themselves, and the ‘Islamic Republic of Afghanistan’, the ruling and internationally recognized legitimate government, will be resolved. The contrasting nomenclatures of ‘Emirates’ and ‘Republic’ encompass a whole set of issues, beginning with power-sharing between the Pashtun and other ethnic groups to the status of women. To what extent the Taliban will pragmatically compromise in dealing with the present government is, therefore, the key to the future but it remains very much an open question.

If the US-Taliban agreement and the run- up to it have dominated the news cycle from Afghanistan for the past few months, things have not been static either when we look east of the Durand Line — in Pakistan. The Pashtun Tahafuz Movement or the Movement for Restoration of Pashtun Pride suggests that politics in the tribal areas of the old North West Frontier Province (now Khyber Pakhtunkhwa) is also entering a new phase and the change is expressed by peaceful, street-level political activism by the young Pashtun.

The PTM came to attention from 2018 onwards as a youth movement protesting against State high-handedness in the tribal areas along the Durand Line in particular but also elsewhere in Pakistan. The movement had emerged in the wake of major military campaigns the Pakistan army undertook in the tribal areas from 2015. This had effectively broken the power of the Pakistani Taliban but the resident population suffered huge collateral damage in terms of displacement, loss of livelihood, human rights violations and, most of all, a general sense of discrimination and alienation on account of being ethnically profiled as terrorists.

In the period since, the PTM’s well-attended rallies across the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa — in the tribal areas but also in Karachi and Islamabad — demonstrated how deep is the angst among the Pashtun, especially its younger generation.

The Pakistani State reacted largely in terms of a traditional approach that it has always employed against ethnic movements or those based on subnational narratives. The statist view in Pakistan — this is largely a military view — has consistently been that ethnic or linguistic loyalties are contrary to the fundamental idea of Pakistan’s Islamic identity and character.The PTM was therefore accused of sedition, being supported by Afghanistan and India — in brief Pakistan’s traditional concerns on its North West frontier.

It is true that the PTM and its young leaders do evoke for many a Pashtun a voice from the last century — Badshah Khan and his Khudai Khidmatgars. This was Pashtun nationalism deeply permeated by the spirit of Gandhian non-violence. The non-violent aspect was important because it was significantly against the prevalent orientalist and colonial narrative of the Pashtun as a violent people. In the case of the PTM too, its non-violent and political approach is a studied contrast to existing stereotypes about Pashtuns that have accompanied, and have been reinforced, since the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 1979.

Yet the similarities between the PTM and the Pashtun nationalism of the 20th century end there. Badshah Khan and his followers remained unreconciled to the two great geopolitical divides of their time — the division of the Pashtun between Pakistan and Afghanistan through the Durand Line and the denominational division of India through the Radcliffe Line. The association between India and Afghanistan was, therefore, strong throughout Badshah Khan’s life and influential also on many of his supporters for decades. This led to long periods of incarceration in Pakistan. He was buried in Jalalabad in Afghanistan — a symbolic evocation of Pashtun unity straddling the Durand Line.

The PTM has not displayed any such inclinations. It is a movement led by the young, educated Pashtun demanding rights very consciously as Pakistani citizens. It is unwilling to accept a second-class status that comes from being located in a geopolitical fault line that has seen nothing but conflict since 1979 and, in particular, since 9/11. If there is one factor that permeates the PTM, it is the experience of conflict. Its critique of Pakistan State policy is essentially that it has fostered such conflict in furtherance of geopolitical ambitions vis-à-vis India and Afghanistan. Much of the political antipathy it displays towards the Pakistan military and the hostility and suspicion with which the latter, in turn, regards PTM supporters arise from this critique of State policy.

Can we see these developments in Pakistan on the same frame with the drama under way in Afghanistan? If both are instances of a ferment amongst the Pashtun on either side of the Durand Line, the differences are also numerous. The PTM derives its appeal from a conscious narrative of de-securitization of the Pashtun homelands in Pakistan. Their demands are for rights granted by the Pakistan Constitution but trampled over the years by State agencies. The Taliban across the Durand Line derive such legitimacy as they possess from resisting foreign intervention in Afghanistan and stand on the threshold of vindication by having worn out the US by armed attrition. De-securitization is not central to their narrative and this is what fills the future of Afghanistan with such foreboding.

The author is a retired diplomat. His latest book is History Men: Jadunath Sarkar, G.S. Sardesai, Raghubir Sinh and Their Quest For India’s Past