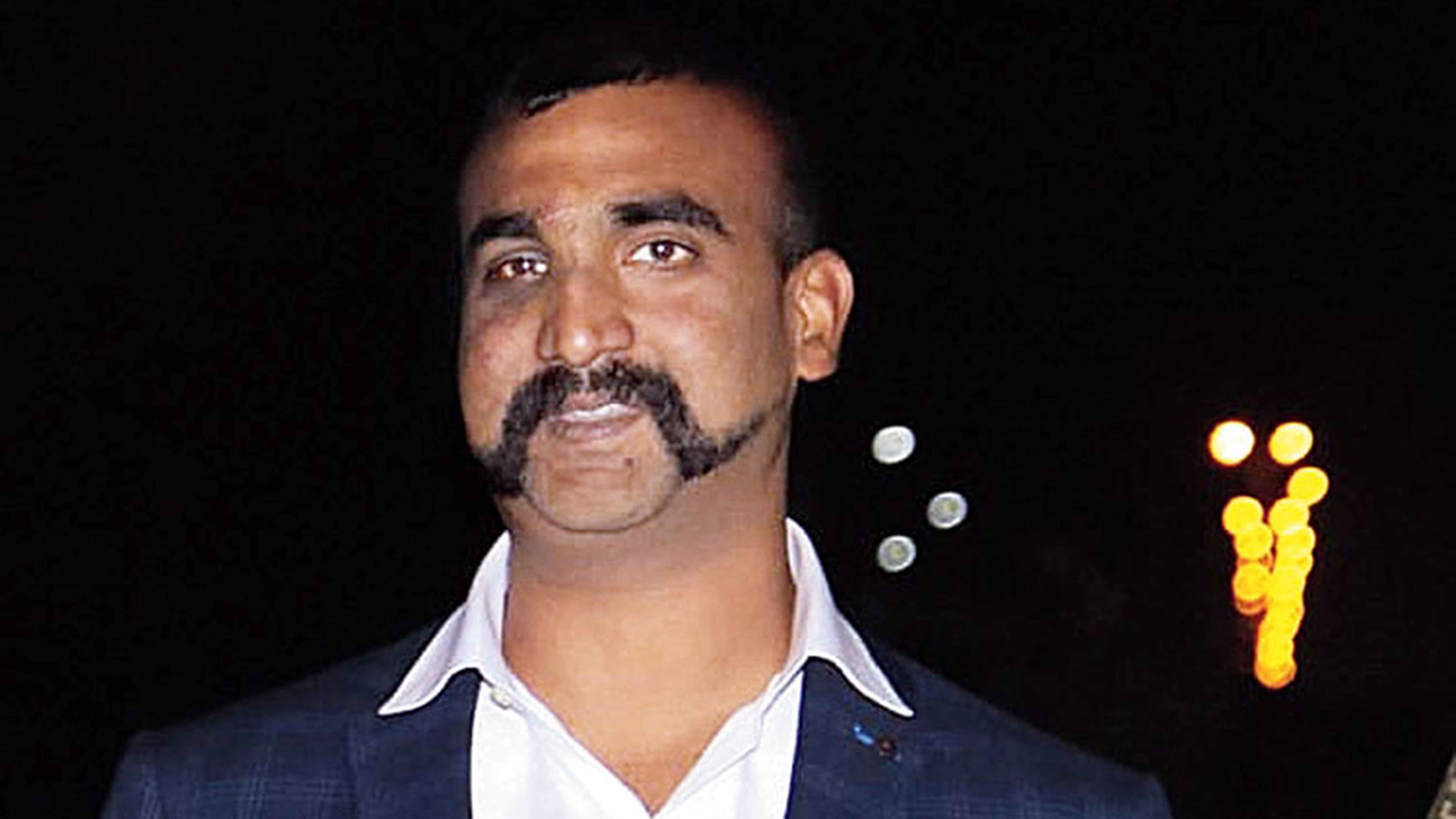

Seeing Wing Commander Abhinandan Varthaman answering a volley of questions put forth by his interrogators and, later, walking tall across the Wagah border reminded me of my trips to Chittagong as an officer of a merchant ship to bring back thousands of Pakistani prisoners of war 48 years ago.

The instrument of surrender had been signed in Dhaka on December 16, 1971. During the next couple of days, there were a number of helicopter sorties landing in the Calcutta Maidan, close to Fort William. We were staying nearby in Hastings, and would run to get as close as we could to the helipad to see the army personnel returning from newly-born Bangladesh. The disgraced lieutenant-general, A.A.K. Niazi, was also bought back on one of these flights and whisked away in a car.

I joined the Shipping Corporation of India’s passenger ship, M/V Andaman, as a junior navigating officer in January. One fine February day, while berthed at Calcutta, we were told that the ship would sail out on an urgent basis the next morning. Every one guessed that the change in plans had something to do with the recently-concluded war.

We set sail the next morning with a minimum crew so as to have maximum sleeping space on board. An officer from the navy had boarded before departure and we were soon informed about the destination — Chittagong. The mission was to bring back some of the 93,000 Pakistani PoWs to Calcutta. The war had ended about two months ago. But excitement and fear were writ large on many faces because it was known that the Pakistanis had heavily mined the approaches to Chittagong harbour. In fact, one of our merchant ships had already sunk in the outer harbour.

Our vessel arrived safely at Chittagong outer harbour. We picked up a local pilot and went up the Karnaphuli river. What we saw remains etched in my mind till date. The river was strewn with the remnants of bombarded and sunk merchant ships, a testament to the brave acts of our air force and the naval pilots from INS Vikrant.

Soon after berthing, detailed plans for boarding the PoWs were made in consultation with the army personnel on board. My father, too, was in Chittagong: he had come on a Calcutta Port Trust salvage vessel to clear the navigational channel in the river. We met and planned to go out for a meal in the evening.

Evening went well. Seeing two Sardars in civil dress got the locals excited: they kept on shouting, “India-Bangla bhai bhai”. Neither the rickshaw drivers nor the small restaurant owner accepted any money from us. I still remember the pride I felt for our army and navy that day. It was on account of their valour that we were being bestowed with such hospitality. The next morning, we took vantage positions to see the PoWs boarding. About 100-odd Indian army personnel were on board to escort around 1,500 PoWs. The latter arrived in trucks and their junior officers took charge under directions from Indian army officials. Officers till the rank of major were assigned the space allotted for ‘lady passengers’, which was a partitioned area. The senior officers were kept in the ship’s hospital, which could accommodate about 10 of them.

The PoWs carried their own rations and used the passenger galleys for cooking and distributing food among themselves. The senior officers were brought into the officer’s mess under the escort of Indian army personnel and were served the same food as the ship’s officers.

There were a number of minor arguments between the PoWs and some of our army officials. I heard the Geneva Convention being mentioned. At the time, I did not know about the convention but learnt some salient points from the young Indian army officers.

Besides the excitement of being close to enemy PoWs and being cheered on by locals ashore, there was an unexpected emotional moment at the end of the trip. When we berthed at Calcutta’s King George’s docks, an Indian army colonel came up the gangway and was given the list of PoWs by army officials on board. He was to take charge of the disembarkation of the PoWs from the ship to a waiting train. On glancing through the list, the colonel said that he wanted to see the Pakistani air commodore who was the senior most PoW on board. I was sent to bring the air commodore from the ship’s hospital. When the colonel met the PoW air commodore, both men immediately saluted and called each other “Sir”. The eyes of both were moistened. We came to know later that before Independence the air commodore had been an officer at the institute where the colonel was a cadet undergoing training. Partition took the men on different paths; war brought them face to face, once again. Only this time, their loyalties differed.

We made another voyage to Chittagong and brought back 1,500 PoWs. My only regret now is that we did not have mobile phones those days to capture the glory that our forces had brought upon the nation. A video shot on a mobile, if it had been made, would have certainly gone viral.