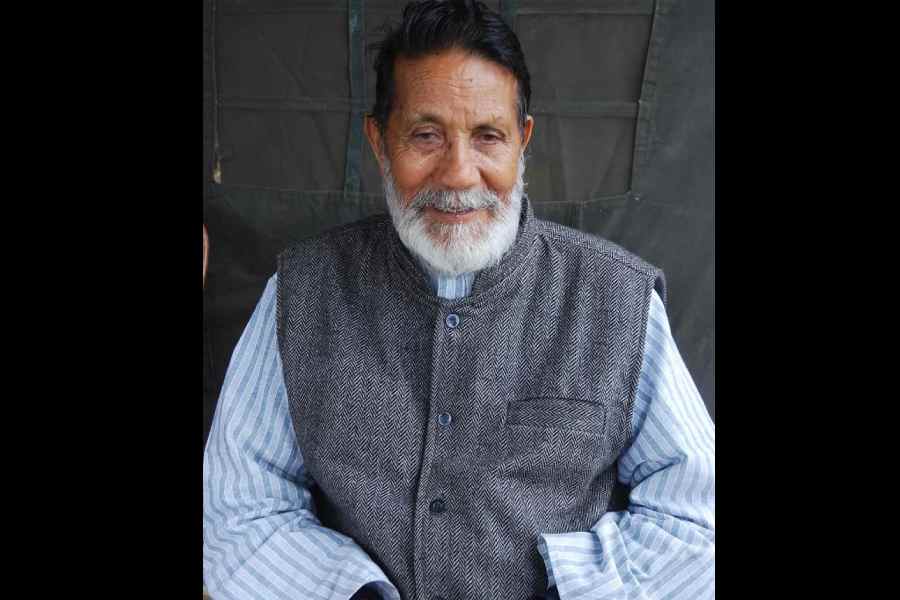

An Indian I greatly admire is the social worker and pioneer of the Chipko movement, Chandi Prasad Bhatt. My first meeting with him, when I was in my early twenties, had a transformative impact on my life. I have met him many times since, each encounter providing fresh insights into the moral, political and environmental challenges that confront India and the world, and what might be done to contain them.

Some years ago, Chandi Prasad Bhatt published his autobiography in Hindi. This has now been translated into English by Samir Banerjee under the title, Gentle Resistance. Bhatt was born in 1934, when India was still a colony of the British. The early chapters contain vivid recollections of his childhood as well as moving portraits of his elder sister (to whom he was deeply attached), of his teachers, of village elders, and of individuals from the labouring lower castes. In these pages, the landscape of the middle Himalaya, its hills, forests, fields and rivers, also come alive. “I loved the flowing waters of the Alaknanda,” he writes, “and felt quite emotionally inspired by the river’s rhythmic flow.”

As a Brahmin, the young Chandi Prasad enjoyed a high social status. However, this did not come with affluence. His father died when he was one. The family was poor though not destitute; as he writes, “all through my childhood we lived in an economy of continuous scarcity, nothing being in abundance, there being never enough money, and every commodity that we were in need of seeming insufficient.” The teenage boy had to plough their land and graze their cows to keep the home fires burning.

Chandi Prasad describes, with charming candour, how he was an indifferent student, having difficulty passing examinations and shifting from school to school before he could successfully matriculate. A university education was out of the question; fortunately, a job as a booking clerk at a local bus company provided a modest monthly salary. The buses transported pilgrims to the holy shrines in the Himalaya, and meeting Indians from different parts of the country in the course of his work broadened his cultural and geographical universe. When he was twenty-two, Bhatt saw his first motor cars, ferrying members of the wealthy Birla family to the shrine in Badrinath. “I never got to see an actual Birla,” he remarks, “but the sartorial excellence of their drivers gave me an adequate idea of their elevated status.”

In 1956, the admired Gandhian social worker, Jayaprakash Narayan, visited the part of Garhwal where Bhatt lived. The young man went to hear him speak; as he recalled sixty years later, JP’s “words touched me to the core of my conscience.” Bhatt then met a local Sarvodaya activist, Man Singh Rawat, accompanying him on padayatras across the hills. The words of JP and the example of Man Singh inspired Bhatt to leave his job with the Garhwal Motor Owners’ Union and devote himself full-time to social work.

In the 1960s, Bhatt worked with colleagues in forming labour co-operatives and Mahila Mangal Dals (Women’s Welfare Associations). He sought, gently, to combat caste discrimination, while also rescuing victims of floods, bus accidents, and so on. By the end of the 1960s, he had acquired a considerable standing as a social worker in Garhwal.

Meanwhile, Bhatt had begun to closely study the depredations of commercial forestry in the hills. He writes with some feeling of the exploitation of nature and of humans through the logging of natural forests by labourers paid a pittance for their work, the bulk of the profits going to the contractor who sold the wood to factories in the plains. Watching the devastation, Bhatt asked himself: “Could this exploitative madness be stopped?” He thought it could, but only if the hill people could once more regain control of their forests, which were so critical to their own subsistence and survival.

In 1973, Bhatt was instrumental in organising and leading the first protests by villagers against commercial forestry that have come to be collectively known as the ‘Chipko Andolan’. Dozens of books and scholarly articles have been written about Chipko. I myself devoted my doctoral dissertation to the movement and its historical origins. What makes Bhatt’s memoir different and distinctive is described by Samir Banerjee in his ‘Translator’s Note’. “The nature of academic narrative,” remarks Banerjee, “is seldom conducive to revealing the human travails, hopes, and feelings, that are embedded in grassroots activism; the world of feeling in the activist’s life is mostly lost within a universe of words, sentences, languages, and ‘isms’ that belong to or derive from explanatory, interpretive, and analytic frameworks that are alien to earthy and more straightforward realities.”

The truth in Banerjee’s remarks is illustrated by, among other things, Bhatt’s encounter in the year Chipko broke out with a senior bureaucrat in Lucknow whom he had gone to meet to press the case for community, rather than State, control of the forests. Here is how the social worker describes his entry into the bureaucrat’s office: “I greeted him but he did not respond. After a few repeated namaskars and no response, I sat hesitantly in the chair in front of him. After some time he lit a thick mud-coloured cigarette — later someone told me it was something called a cigar much liked by ‘Burra Sahibs’. Exhaling smoke, he turned to me and asked, ‘What is all this you are doing?’ Glaring and puffing, he kept blowing smoke at me. I tried to give him our perspective, but he was not interested. His worldview seemed to be in line with that of the normal run of bureaucrats — hill peasants were contemptible and their small units were boils on the magnificent body politic which it was their duty to keep in shape.”

Contrast this pen portrait with another that Bhatt offers, equally vivid but far more empathetic. This is of the remarkable Gaura Devi, the leader of the Chipko protest which occurred in the village of Reni in March 1974, exactly fifty years ago as I write. She had never seen a school, and was widowed early, making a precarious living ploughing her small plot of land. She nonetheless found the time and energy to start a Mahila Mangal Dal in her village in 1965 and, nine years later, to lead what is perhaps the most iconic of all the Chipko protests in the history of the Himalaya.

Gaura Devi died in 1991, “leaving only the luminous and inspiring strength of her gentle resistance to guide us in the fight against inequality and oppression.” Her “urge to fight oppression,” writes Bhatt, “came from the ordeals of her life and those of her fellow women who had for generations been trying to cope with poverty and personal tragedy.” Her steely courage was combined with a deep compassion; so, as the man memorialising her observes, “it is impossible for me to forget the grace within her that compelled her to say, soon after she and her companions had stopped the felling of trees near Reni, that despite the boorish behaviour of the woodsmen I should not speak ill of them to the authorities lest they lose their livelihood.”

Elsewhere in the book, Bhatt offers this pithy definition of the movement of which he was the moving spirit: “The Chipko agitation has been one way of awakening the latent empathy of hill villagers for their forests, and the transformation of an inner sentiment into a social commitment.” This commitment was expressed not merely in protesting against forest destruction but also in taking the lead in forest restoration. Under Bhatt’s leadership, Chipko volunteers worked with villagers to regreen many barren hillsides in Garhwal with salutary effects on the local ecology.

Bhatt is principally a grassroots organiser, yet he is also an insightful thinker, particularly with regard to sustainable economic practices. As early as 1976, he warned that reckless road-building was contributing to the collapse of houses in the town of Joshimath. In the 1980s, he wrote several landmark essays explaining why large dams were not suitable for the Himalaya. “I sense my already fragile mountains have become progressively more fragile,” he writes, this is a result of the fact that “humanity is now alienated from the land and natural resources they live on. Commercial interests have taken over everything, and mental and emotional changes as well as adaptive processes have followed to align people to commerce.”

Chandi Prasad Bhatt’s autobiography is a vitally important book. The narration of his own experiences provides rich insights into social and environmental history as well as the history of Gandhism after Gandhi. The book is also a document of some literary worth. I trust it shall obtain the wide readership it deserves.

ramachandraguha@yahoo.in