Mona Dash’s book, A Roll of the Dice, begins in Calcutta on June 22, 2000, when she is summoned home from the office to find that her eight-month-old son, Akshyat, has died. Administered a BCG vaccine, he developed tuberculosis. This is because, unknown to his parents, he had inherited a defective gene from his mother which had given him a condition called severe combined immuno-deficiency. This meant he did not have the white blood cells necessary to fight off infection. Mona sees her husband, Kaustubh, carry off a little bundle for burial.

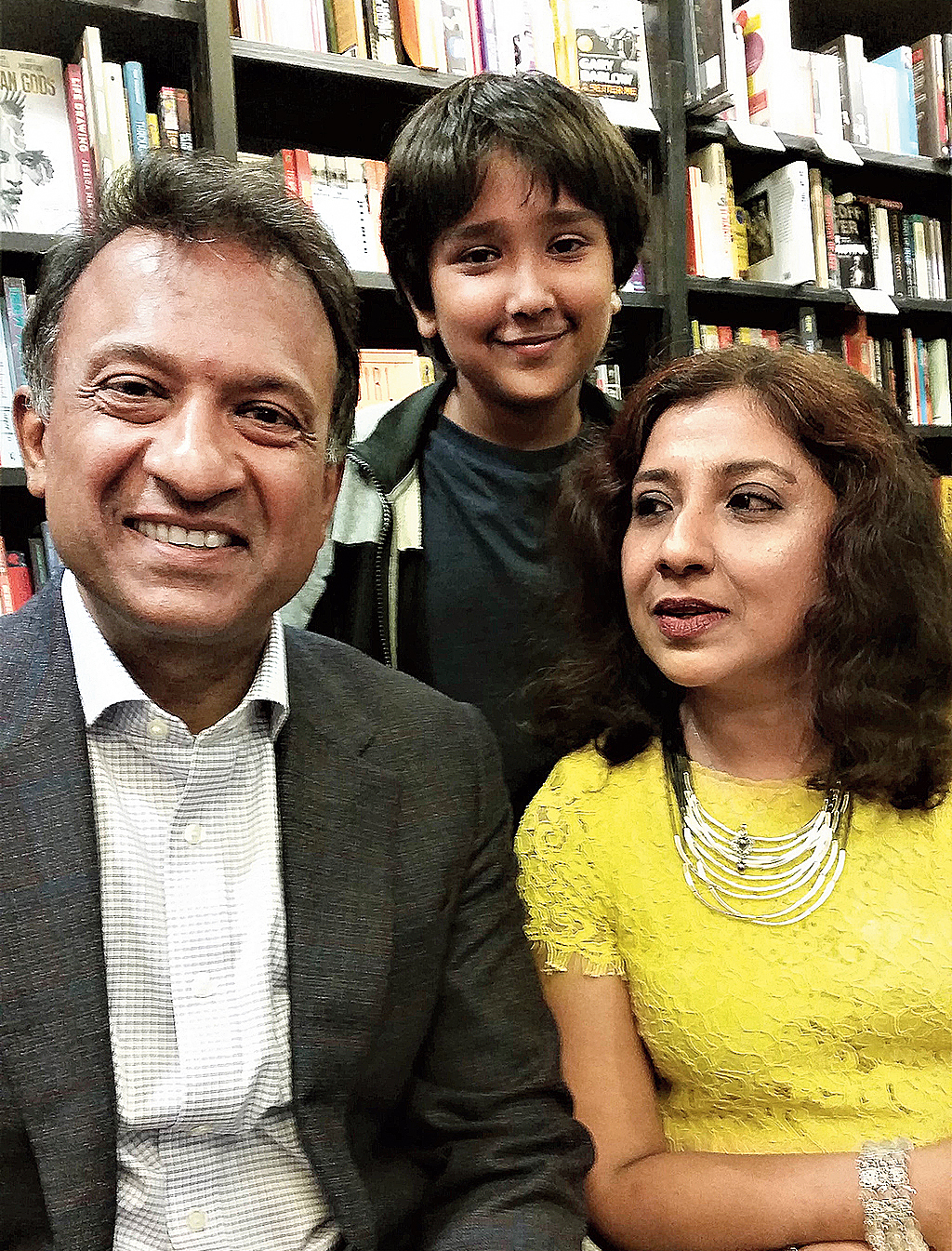

Mona and her husband move from Salt Lake to London, where their second son, Krish, is born prematurely on February 8, 2007. A test done immediately confirms that he, too, has SCID. But he is rushed to the Great Ormond Street Hospital for children, where “the tiniest baby we had seen” comes under the care of Bobby Gaspar, professor of paediatrics and immunology. Thanks to a transplant of vitally needed bone marrow from his father which Krish received at six weeks, he is today a healthy 12-year-old. At his mother’s book launch at Waterstones in Islington, north London, he tells me his hero is the England bowler, Jofra Archer, and demonstrates his own fast-bowling action. His follow-up looks pretty good.

Gaspar, who has written the introduction to the book, is campaigning for all babies born annually in the United Kingdom to be tested for SCID at birth. He would like the same to happen in India.

“[I]f you leave children undiagnosed then roughly half or more of the children will die from the disease,” he warns. Mona says: “Somebody read the book and said, ‘I feel sorry for you.’ I said, ‘You don’t need to because I have gone through so much it makes me a different person’.”

Dinner guests

Sarosh Zaiwalla, a well-known Indian solicitor in London who recently won an important victory for the Bank Mellat of Iran against the British government, tells me he is writing his memoirs. I found a copy of an article I did in the Daily Telegraph that Sarosh requested. It is about how John Major marked the first anniversary of his premiership in December 1991 by hosting a dinner at 10, Downing Street, for a group of eminent Indians. From the table plan I see Sarosh was there, along with Amitabh Bachchan and the Hinduja brothers, Gopi and Prakash. But guess who was sitting to the left of Major? Step forward, Vijay Mallya.

Tough education

How come one school — Eton College — has produced so many British prime ministers, Boris Johnson being the 20th? Starting with Robert Walpole in the early 18th century, the list includes Anthony Eden, Harold Macmillan, Alec Douglas-Home and David Cameron (who was accused of inducting too many “Eton cronies” into his cabinet). To be sure, the brotherhood of batchmates could apply to any school, not least The Doon School in Dehradun, which was modelled on Eton.

Aficionados of PG Wodehouse will know that Bertie Wooster and most of his pals went to Eton, which perhaps gives an unfair impression of the school’s academic prowess. It is actually remarkably rigorous. However, in Britain in recent years, there has been a campaign aimed at preventing “public school educated toffs”, especially OEs (Old Etonians), rising in life. Asked whether the PM’s job would make Boris nervous, his father, Stanley, said: “I very much doubt if he’s nervous. This is a man who’s been through a tough English education.”

No room for nonsense

The Royal Society does not care for scientific mumbo-jumbo, as its president, Professor Venkatraman Ramakrishnan, made clear recently in London while presiding over the admission of 62 new Fellows, several of them of Indian origin. It is known that the 2009 Nobel laureate for chemistry has little patience for the nonsense spouted by some Indian politicians who claim that the country could boast of transplant surgery and flying machines even in mythological times. “The Royal Society was an early advocate of what is now known as the scientific method,” stressed Venki. “Its motto — Nullius in verbaor, roughly ‘on nobody’s word’ — is the philosophy that new knowledge is acquired by observation and experiment, that is, it is evidence-based. In doing so, the Royal Society helped win one of the major debates in science in its time and influence the subsequent course of science.”

The elected Fellows included Gagandeep Kang, executive director, translational Health and Technology Institute in India; Anant Parekh, professor of cell physiology at Oxford; Gurdyal Singh Besra, professor of microbial physiology and chemistry at Birmingham University; Akshay Venkatesh, a professor at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey; and Manjul Bhargava, a professor of mathematics at Princeton. Akkihebbai R Ravishankara, professor in the departments of chemistry and atmospheric science at Colorado State University, was made a Foreign Member. The applause seemed loudest for Yusuf Hamied, chairman of Cipla, who was made an Honorary Fellow.

Yusuf Hamied (right) with Stephen Toope. (Picture sourced by correspondent)

Footnote

Yusuf Hamied celebrated his honorary fellowship of the Royal Society by hosting a dinner at his alma mater, Christ’s College, Cambridge, for 30 of the surviving 73 students who were freshers in 1954. I was a guest, as was the vice-chancellor of Cambridge, Professor Stephen Toope. He said he visits India twice a year partly with the aim of stopping the best Indian students from going to the United States of America and applying instead to Cambridge. I urged him to visit Calcutta.