The end of the year makes you want to sum up the months, introspect and feel some kind of hope. I don’t know which of the three is the most difficult to do, but I will give all of it a shot. I will not talk about the world, for its violence at the moment is quite incomprehensible; I cannot talk about the country, for everything here is headed towards a temple. I will not talk about the state or my city, Calcutta, for various reasons. What I will talk about is my neighbourhood — and go a little beyond just the past year.

I moved into this old, quiet, affluent neighbourhood in South Calcutta, where I feel like an impostor at times, a little more than 12 years ago. These are not exactly sylvan surroundings, but you do see and hear many birds in the neighbourhood. But since I moved in, many changes of sights and sounds have taken place, the most constant one being the disappearance of old houses. These houses, beautiful in what is perhaps best described as the South Calcutta style of architecture, are routinely demolished and replaced by multi-storeyed buildings. Such an act of ‘development’ affected us directly when the old building in a corner plot diagonally opposite the house that I live in was shrouded up one day and removed. It was like an execution, clean and swift. A multi-storeyed came up quickly in its place.

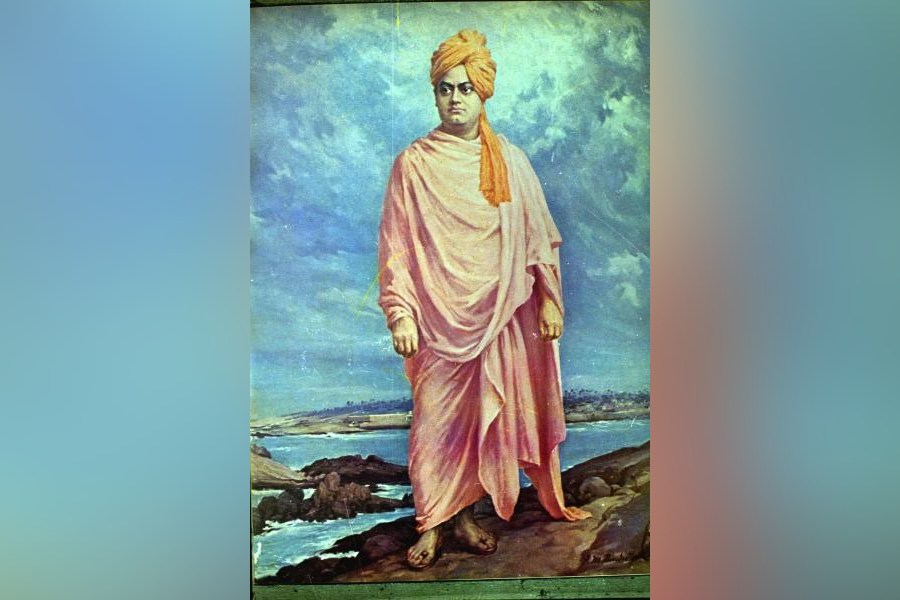

Next, a new element was introduced to the neighbourhood. One day, we woke up to the sight of more construction. Quickly again, a structure was built facing the new building and soon a Vivekananda bust was installed on it with much fanfare by the local political community. So Vivekananda, from his vantage point, was subjected to a rather wide view of the neighbourhood. One of the first things that he saw was the felling of a large tree, unannounced and done without any permission, in front of the new building. The tree was coming in the way of the cars that came to the building.

More sound was to alter the neighbourhood. On the following January 12, Vivekananda’s birthday was celebrated by the local authorities. It was as if a sound bomb had been dropped on us. The immediate impact, if measured only by decibel levels, exceeded that of Vivekananda’s Chicago speeches by far. The neighbourhood grew more contemporary. The ground floor of a building facing us was converted from a residential apartment into a high-end vegetarian restaurant. The quiet locality began to ring with resonating ‘Love you, see you’s’ till almost midnight.

Indians, cutting across classes and communities, display a touching innocence about the noise they generate. The good thing about the quarantine months was that they brought back some silence. The restaurant shut down during the pandemic. A few months earlier, the premises were opened again, though it was now an office full of young, well-dressed people. However, no one understood their hectic activity. The office bore no name; the young employees did not look accessible. Unable to contain my curiosity, I walked through the glass doors one day and was told that the office worked with online data. Their business was obviously booming, as the number of young men and women began to increase; glued to their phones, they now began to spill over into the pavement along our house. I had no choice but to become privy to their conversations, mostly conducted in English. I suddenly realised that they were selling online courses on astrology and palmistry. These were perfectly structured, neatly packaged courses, and seemingly in great demand from would-be professionals.

I was witnessing the birth of New India. So was Swami Vivekananda, who had always exhorted the nation to awaken, arise and achieve its dream, and whom all political parties like to stake a claim on. But recently I woke up one morning and found that Vivekananda’s face was turned away, just a little.