Ninety is a great number. And a terrific age.

Having crossed eighty, ninety walks with the measured steps of emeriti.

Being at hundred’s door, it carries the bounce of penultimacy.

A full decade short of a century, it has a venerable vivacity. It has a certain life to it that previous ‘round’ numbers do not.

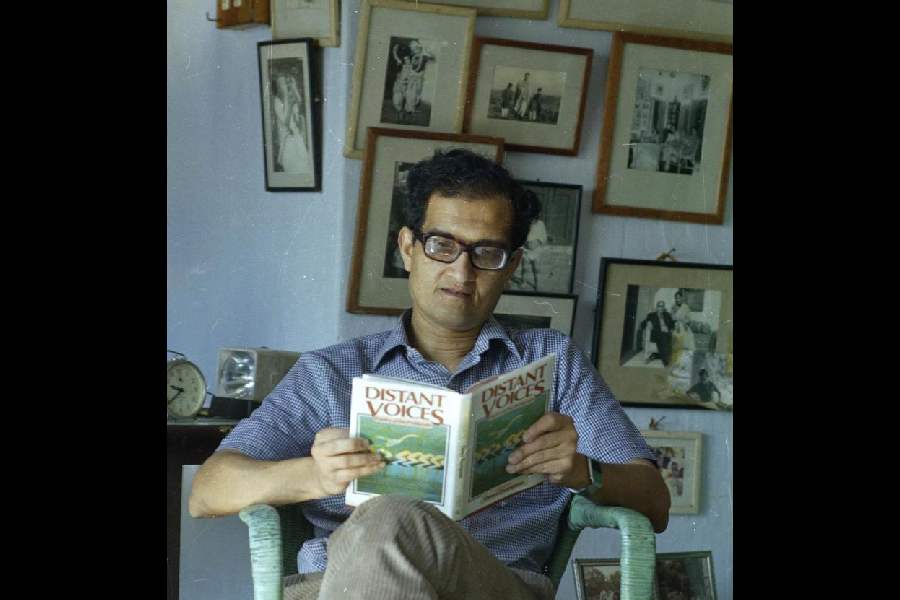

Amartya Kumar Sen, who turned ninety this month, was treated just the other day to a pre-birthday joke by the grace of social media. The Nobel Laureate was said to have died. The ‘news’ zoomed across the globe, not because death makes news but because Amartya Sen does. Newspaper offices went into nervous action, defrosting draft obits of the great man. Editors checked out their ‘regular’ columnists on who could write fresh tributes fast. Photographs were dug up from their archives for the ‘classical young Sen’ with enigmatically attractive eyes storing econometric puzzles and also those of the most recent ‘Sens’ with the same eyes wanting relief from today’s horrors. And, indeed, some ‘well-known contemporaries’ were called up to be given the ‘sad and as yet unverified news’ and urged to put fingertips to keyboards for a tribute ‘while we get confirmation’.

The world’s sharpest master of welfare economics and social choice theory would, ordinarily, have laughed the joke out but for the fact that his laptop’s inbox and mobile telephone were, within seconds, clogged with incoming messages expressing shock, disbelief, and ‘tell-me-its-not-true’. And when before too long the hoax was bluffed out came the next round of messages including one, I must admit, from me: ‘Greatly relieved’, ‘Thank God…’ and ‘Now… for your hundredth…’ I do not think the historian of famines was amused and was going to reply to any of these. ‘Better ways of using my time…’ I could hear him say under his breath.

He would, therefore, be glad that his ninetieth birthday has gone almost unnoticed. ‘Better ways of spending time, mine and others’ I can hear him say, with a cube of ice clinking concurrence in a glass of something choice to mark the day.

Sen is a hundred things but is, in my thinking, above everything else, a great witness to some grotesque things human beings have done to themselves and to planet earth, as well as truly wondrous things.

In the years immediately after 1933 (the year Sen was born), he could follow, with his generation schooling in Dhaka and then in Santiniketan, the rise of a maniac in Europe unleashing World War II on an innocent world with disastrous consequences: first, the Bengal Famine of 1943 caused, among other factors, by the military policy of the time, panic buying, hoarding, triggered by the war. Second, the manufacture of the atomic bomb and its deployment within months upon a country, Japan, that had ceased to pose any threat to the one that made and dropped two of them on densely-populated cities. Third, the grafting of an artificial nation with a translocated population on a tract peopled by its natural inhabitants. Fourth, the rise of nuclear, biological and chemical weapons with unknown furies. Fifth, the commencement of techno-commercial hegemonies that divided the world into new inequalities, dependencies and enervations.

His time in Presidency College in Calcutta and then in Trinity College, Cambridge, England, saw great counters coming to these horrors in terms of the UNO’s Declaration of Human Rights, the newly-independent India giving to itself a Constitution founded on the principles of secularism, social justice and federal equity, the civil rights movement in the US pioneered by millennial individuals like Martin Luther King Jr and Rosa Parks, and movements of shackled nations starting on the African continent led by men of the stature of Kwame Nkrumah, Jomo Kenyatta, Albert Luthuli and, later, Nelson Mandela. And overarching these healings, arising unmistakably and remarkably, a sense of the importance of the aspirations and entitlements of the individual, especially the traditionally under-acknowledged and marginalised communities.

In the 1970s and the 1980s, came science and technology, transforming life unrecognisably, giving humans a new equation with the resources of the earth and new challenges, leading to Sen’s interest in ‘real wages and using the entire increase in labour productivity, due to technological change’ and saw the appearance of his seminal work, Poverty and Famines: An Essay on Entitlement and Deprivation.

The nine decades in which Sen has moved from being a precocious student to a cherished teacher have also seen his country acquire the skills of an electoral democracy conducting elections of mammoth proportions, in almost each of which he has made sure he has voted. The West Bengal constituency where he is a registered voter has seen him take his place in the queue inching its way to the ballot box (now electronic machine) along with fellow citizens who are perfectly at ease with the Laureate and Bharat Ratna-awardee being one among them.

But these decades have also seen in India new, dire crises, of which five stand out: one, rank callousness as to the damage industrial and techno-commercial exploitation does to non-renewable resources and fragile ecosystems and that which aggressive cropping does to our depleting topsoil and water tables. Two, the continuing low nutrition and basic health levels of the rural poor, especially those of the prematurely ‘married-off’ young and lactating mothers and school-age children. Three, the vulnerability of the rural workforce and unavoidable migration to uncertain and often collapsed pathways. Four, the contamination of our democratic, especially electoral, system by what is unambiguously called ‘muscle and money power’. Five, the brazen undermining of our secular tradition by violent religious bigotry and the equally violent compromising of the rights of the lower castes by swaggering upper caste machoism.

Brooding over all this is a pall of despondency.

Sen’s rigorous examination of what he witnessed and studied has resulted in some of the most defining writing of our time, such as his celebrated article in The New York Review of Books, “More Than 100 Million Women Are Missing”, in which he shows the impact of inequality on mortality. His book, Development as Freedom, suggests likewise, that ‘real freedoms’, and not metrics such as GDP or income-per-capita, are what matter.

The present situation of quandaries and complexity is beyond the capacity or even the comprehension of administrators, politicians and technologists. The wondrous opportunities being opened by Artificial Intelligence and, equally, its mind-numbing potential for harm, for instance, beyond the reach of intellectual or academic intervention. We cannot be so naïvely aspirational as to wait for ‘someone’ to emerge and redeem us from our sense of being trapped in a hovel of despair, within a ruin of hopes. We have to seek and find within our own human resources the knowledge, understanding and discrimination that Amartya Sen has shown over these decades. The ‘joke’ I mentioned evaporated in the fakery it came from. But it did make us see for one shuddering moment what life without Sen can be. It showed up for that ‘Oh, no!’ moment the drought in our time of social philosophers and generational motivators whose word carries truth, veracity, courage and total objectivity.

Is Sen a Marxist? I do not think he will want to contest that. Is he an atheist? I doubt if he would care to proclaim his thoughts on the matter. A dialectical materialist? I would

say he is, above all else, a scholar-witness in the open university of the human condition. And one who sees in music and sculpture, in a great film and a fine piece of writing, the ‘click’ he can find in any mathematical theorem.

“Valuationally gross” is a phrase he used some years ago to describe India’s (then) attitude to the struggle for political rights in Myanmar. It is that unceasing attention to the life-giving and life-taking pulsations of our time that has made Amartya Sen who and what he is.

With two wars of vile ferocity blazing, the world’s terror modules plotting the next blow and politics getting drained of principles, we need the statesmanship of this independent scholar-witness more than ever. Speak to your mind’s extremis, Amartya-babu. Let your keyboard’s letters pale and numerals fade under your moving fingers’ scorching veracity.