In the recent speech she gave while accepting the PEN Pinter Prize for 2024, Arundhati Roy forensically laid out the different aspects of the genocide the Benjamin Netanyahu regime has been committing before our eyes and cameras for over a year. Like others before her, including highly respected commentators in Israel and Jewish intellectuals outside that country, she forced us to confront this ongoing mass murder and ethnic cleansing that has been going on for far longer than most people had anticipated. She joined her formidable articulation to that of others to show how the United States of America and other developed countries have been knowingly complicit in this slaughter and starvation of the civilian population of Gaza and now the attack on Lebanon. Reading the speech, one was yet again thankful that we have someone like Roy to speak truth to power not only in India but also in the international arena.

There was, however, one thing she said that bothered me, just as it had before. Coming to Hamas, Arundhati Roy said: “I refuse to play the condemnation game. Let me make myself clear. I do not tell oppressed people how to resist their oppression or who their allies should be.” In this Roy has been consistent — I was immediately reminded of similar statements she had previously made vis-à-vis the movements in Kashmir and the Maoist insurrection in Central India, words to the effect of: I myself could never pick up a gun for this (or one guesses any) cause, but I can understand the reasons why someone else might.

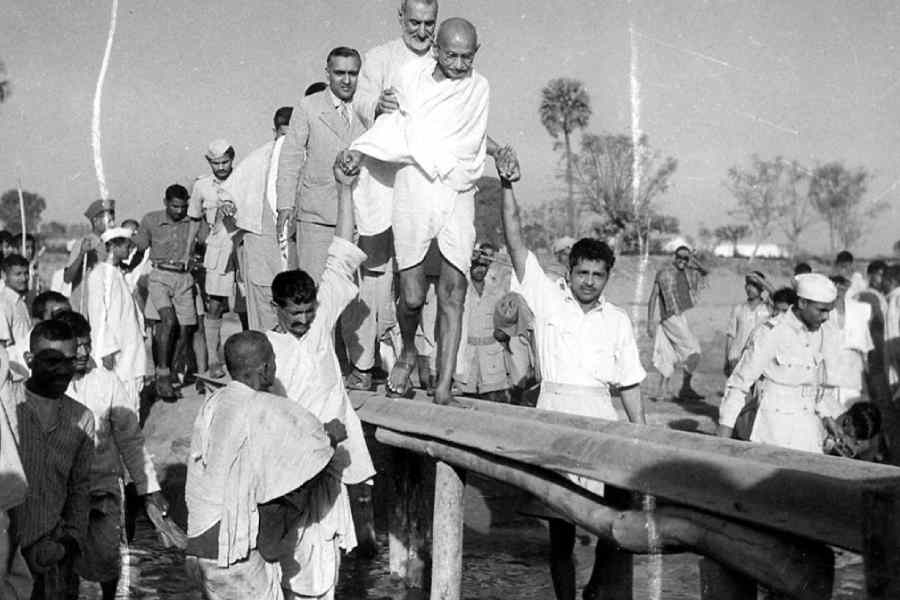

Roy’s dismissals of Gandhi are well-known, as is her championing of Ambedkar in the MKG versus BRA match-up she posits. She has also acerbically pointed out that Gandhi’s ahimsa had at its core a performative element that depended on the national and the international press covering the brutal suppression of those who were offering non-violent resistance. Roy argues that it’s very hard for an Adivasi or a Dalit to see why they should get murdered while protesting non-violently in a corner of India where there is no media present to record that sacrifice (to which one can now add the hard-wired indifference of pro-establishment propaganda outfits posturing as news organs).

Furthermore, in India today, we witness in full public view the long-term jailing of peaceful activists and government critics without evidence or trial and what one can only call the execution-by-incarceration of those with frail health among the targeted victims. These imprisonments to the point of death are carried out under the gaze of a legal system that seems to be oblivious to the principle of ‘innocent until proven guilty’, followed by the absence of widespread outrage at these baseless jailings and de facto deprivations of life. Seeing this, Roy’s argument seems to garner even more weight.

And, yet, there are problems with this thinking that just won’t go away. First, at a basely amoral level, there is the question of strategy and tactics. Many people have lauded Gandhi for quickly recognising that a violent uprising and a ‘war’ for independence, no matter how massive, was not winnable against what was then the most powerful army in the world. Where the people would have had sticks, bricks, swords and a few small firearms, the British had machine-guns, advanced artillery, tanks and these new things that flew in the sky and rained down bullets and bombs from above. It would have taken the slaughter of just a few white women and children for the Empire to justify the full deployment of its arsenal — remember what happened in 1857 in Lucknow and Delhi. The massacre that followed would have had the full backing of the ‘World Community’ (read powerful countries run by white men).

Many pro and con arguments dog-fight inside this silo. The British historian, Perry Anderson, argues that Indian independence was won not through ahimsa but only because of the vast orgy of himsa that was the Second World War; this argument can be shot down by pointing out that Anderson’s beloved Bolshevik and Chinese revolutions also only succeeded because of the First and the Second World Wars, respectively. Had these wars not taken place, Gandhi’s non-violence might well have fared far better than the relatively small bands of combatants Lenin or Mao would have led against far superior armies. In fact, Mao’s campaign would not have come about because Lenin would have failed abysmally. Another counter-argument is that Gandhi/Congress weren’t the only players in the independence struggle; the many young bomb-throwers mattered, the communists mattered, Subhas Chandra Bose made a difference (here one remembers Roy’s statement: “I do not tell oppressed people... who their allies should be”), the Naval Mutiny mattered — all of them together made the raj untenable. The counter to that counter is — imagine what an independence movement without the huge unity of the Congress movement and the huge sympathy of the world for ahimsa might have looked like and how it would have panned out.

Another level of argument can perhaps be triggered by quoting Jean-Paul Sartre: “We fight fascism not because we will win but because it is fascism.” Likewise, one can say: we will follow non-violence not because it is a smarter tactic but because it matters what means we employ; in fact, the ends we achieve are sculpted by the means we employ to reach them. This is not the same as saying ‘an eye for an eye makes the whole world blind’ but rather, ‘even in the unlikely situation you are left with some dim sight in one eye, yours will be the blood-clouded eye of a multiple murderer.’

I have no answers to how one stays non-violent in the face of the grotesque violence of a Hitler, a Menachem Begin, an Ariel Sharon, a Netanyahu, a Yahya Sinwar or an Ali Khameini. But the thought doesn’t go away: just as we are unquestioning of the idea of ‘economic growth’, something which has brought us to the edge of planetary disaster, we are also too easily accepting of the idea of ‘justifiable’ violence. As with economic greed so with violence, there is no logical limit or summit to the idea but there is clearly a nadir — at the bottom of the abyss.