The new year finds Indian cricket fans happily befuddled. Befuddled because it isn’t wholly clear how a team that suffered a 4-1 demolition at the hands of England, managed a possible (at the time of writing) 3-1 triumph over Australia inside six months of the earlier rout. One obvious answer is that the English are the more formidable opponents: on current form they have the better batting line up, an embarrassment of riches in the matter of all-rounders and, in home conditions, the more dangerous bowling attack. This Australian team is made up in equal parts of Test match bowlers and minor counties batsmen. This lopsidedness is largely the result of the suspensions being served by Australia’s two best batsmen but even allowing for that, it’s odd that these anonymous triers are the best Australia’s vaunted first-class competition can offer in the absence of Smith and Warner.

The other change that might have helped the Indian team was Kohli’s retreat from his earlier insistence on five bowlers. This change came about at the tail-end of the English series when Hanuma Vihari replaced Hardik Pandya and India lost despite that, but it’s at least arguable that the sixth batsman has supplied much needed stability down the order. Rohit Sharma and Hanuma Vihari alternated in that position through the Australian tour and did enough to underline the importance of six specialist batsmen.

But the three headline successes of the Australian tour have been Cheteshwar Pujara’s batting, the collective achievement of India’s fast bowling trident and Rishabh Pant’s meteoric rise... in that order. There is a case for arguing that the real story of 2018 is India’s pace attack. The consistent ability to take the lion’s share of twenty wickets every match, the fact that the combined returns of Bumrah, Ishant and Shami have begun to rival the records of legendary West Indian pace batteries are hard to comprehend. From a time when Budhi Kunderan and Sunil Gavaskar were given the new ball to take the shine off it, to a situation where opening bowlers as good as Umesh Yadav and Bhuvneshwar Kumar are consigned to the bench, Indian fast bowling has come a long way.

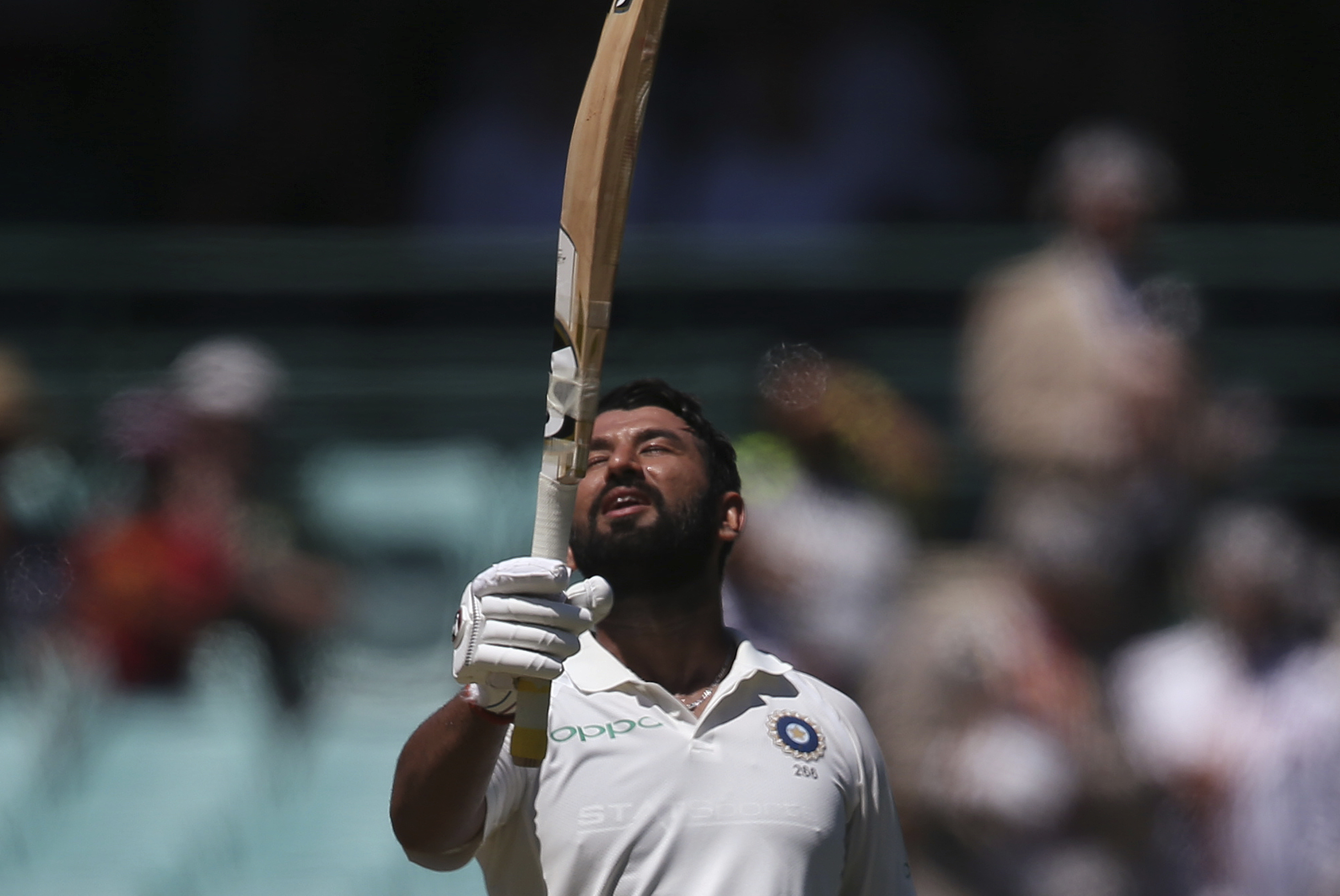

In the context of the success in Australia, though, Pujara’s performance was the crucial variable. India’s fast bowlers consistently bowled the opposition out in England through the summer but they were routinely let down by India’s batsmen with the exception of Kohli and not even his heroics could make up for the failure of the rest of India’s batting unit. In Australia, despite the chronic inability of Murali Vijay and K.L. Rahul to build a platform for the innings, Pujara’s marathon vigils bought time and breathing space for Kohli and the others. By checking in at the fall of the first wicket and refusing to leave, Pujara stopped that first breach from becoming a rout. Kohli wasn’t quite the force he was in England but given the form he has been in for a while, even off the boil, he was always likely to do enough to right the ship with a little help from a friend. One reason why India lost the second Test was that Pujara failed in both innings. Given the dysfunctional opening pair and Rahane’s prolonged loss of overseas form, Pujara’s ability to tire out the fast bowlers, neutralize Nathan Lyon and accumulate big scores, was the foundation of India’s victories.

Not so long ago, Pujara’s average in South Africa, England, New Zealand and Australia was under thirty, scarcely the record you would expect of a top order batsman with an overall career average hovering around the fifty mark. Pundits pointed to his vulnerability outside the off stump, his tendency to be bowled between bat and pad, his ‘low hands’ that made him a candidate for bat-and-pad catches. In these recent series against England and Australia, he has improved that record with four hundreds and two fifties spread over nine Tests. In Australia, because these big scores have been made in a winning cause, much has been written and tweeted about his obvious virtues: his patience and restraint and variations on these unoriginal themes. If I had a rupee for every time I’ve read or heard a pundit praise Pujara’s ability to ‘bat time’ (whatever that means) I’d be a very rich man.

This is exasperating because most cricketing pundits in print and the electronic media are successful former players, hired because they are articulate and knowledgeable. When a player improves his game noticeably in a short space of time, it gives (or should give) pundits an opportunity to earn their keep by using their experience as one-time practitioners to explain the changes in technique that made that improvement possible. Instead we are given patience, Pujara’s inhuman powers of concentration and his ability (god help us) to bat time as all-purpose explanations.

Sanjay Manjrekar, for example, has been critical of Pujara’s technique and ability for some years now. After Pujara’s century in a losing cause in England, Manjrekar suggested, patronizingly, that Pujara ought to be a role model for young cricketers because he demonstrated how much could be achieved by a cricketer of modest talent. After his centuries in Australia, Manjrekar conceded that Pujara had converted him from a sceptic into a believer. This must have been gratifying for Pujara but it begged the question: what had Pujara changed in his game that was helping him hit these centuries? The closest anyone came to producing a technical explanation was Gavaskar suggesting that Pujara was standing higher in his stance than he used to; apart from that it was all patience, concentration and self-denial: A Portrait of the Batsman as a Young Monk.

The third great story of the English and Australian tours was Rishabh Pant’s startling debut year. At the end of his explosive 159 not out in the Sydney Test, Pant’s batting average was a shade under 50. Even allowing for his short career (nine Tests) this is a remarkable record that includes two hundreds, two fifties and a string of 20s and 30s. Pant’s flamboyance and stroke-making actually obscures the fact that he is a consistent batsman who nearly always gets a start. In this Australian tour, he hit a pair of 20s, followed by four scores of 30 and above before rounding things off with a big century. As important as the weight of runs is the unreal dexterity that lets him turn yorkers into boundaries and whip fast bowlers off his pads with a kind of minimalist grace. Despite the fact that he jointly owns the record for most wicket-keeping dismissals, he is less than consistently good as a Test keeper, but given that he’s only twenty-one, he’ll probably improve. Even if he doesn’t, if he keeps up his batting form, he might walk into this team as a specialist No. 6 batsman.

It’s not often that an Australian tour ends in unbridled optimism. So to celebrate the moment, here’s a fantasy eleven for a Test series at home against the English in the near future: Prithvi Shaw, Mayank Agarwal, Cheteshwar Pujara, Virat Kohli ©, Ajinkya Rahane, Hanuma Vihari, Rishabh Pant, Ravindra Jadeja, R. Ashwin, Mohammed Shami and Jasprit Bumrah. If Ashwin stays fit, we’ll kill them.