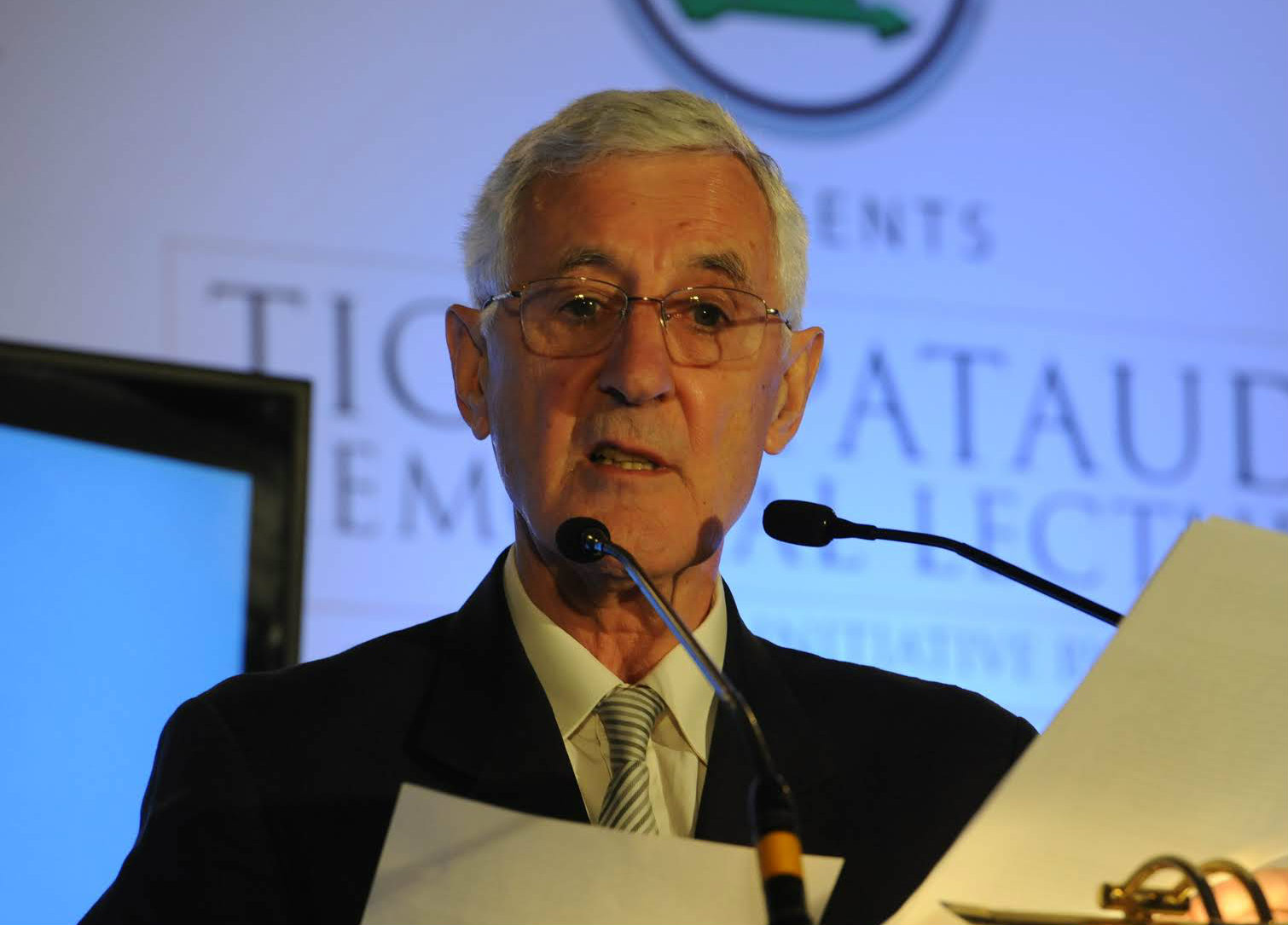

The Australian fast bowler, Rodney Hogg, famously said of the England cricket captain, Mike Brearley, that “he has a degree in people”. Long after the two men had retired from the game, Hogg invited Brearley to a radio show he was hosting. He had recently heard that his old antagonist had begun his first-class career (at Cambridge University) as a wicket-keeper. He now asked Brearley, on air, why he had given up keeping. “I wasn’t very good at it,” answered the Englishman. “But you carried on batting,” responded the Australian.

The story is told in Mike Brearley’s new book, On Cricket, a wide-ranging collection of tributes and reflections. Beginning with a bow to the heroes of his youth, Len Hutton and Denis Compton, the book has sections on his own great contemporaries, on cheating and corruption, on wicket-keepers, on Indian batsmen, and on cricket and race. During his playing days, Brearley was a conspicuously successful captain while being a rather ordinary batsman; the two sides captured so well in those two statements by Rodney Hogg. However, as this book shows, he has continued to think deeply about the game long after he retired. And, as a one-time philosophy don and practicing psychotherapist, he knows about life beyond the boundary too.

The forty-nine essays of On Cricket are redolent with empathy, understanding, knowledge, and an often self-deprecatory humour. So a chapter on Dennis Lillee (“the best bowler I played against”) ends with this line: “It has been a privilege to know him and indeed to have batted against him, however ineptly.” Brearley also writes with feeling of the great West Indian speedsters of his time. Reading this book, it strikes me that fast bowlers who threatened the wicket as well as the body seem to have disappeared from the game. There is no one now playing who is remotely as fearsome or frightening as Lillee or Thomson, Holding or Roberts, Waqar or Shoaib, were in their pomp.

Brearley can be extremely illuminating about the cricketers who came after his time as well. Here is his characterization of the technique and style of the greatest Sri Lankan batsman of all time: “Sangakkara was usually the rock around which his team’s batting success, and sometimes its survival, was built. He was the most sturdy, the most correct, of them all. If he were a motor bike he’d be a Harley-Davidson — well-built, stable, packing a punch. The ball always made a solid clunking sound on his bat. He played with a steady head, strong body and hands, and exceptional ability both to judge length and line, and to adjust his balance accordingly.”

Brearley has a long and close connection with India. He is married to the architect and designer, Mana Sarabhai, whom he met in Ahmedabad on the MCC tour of 1976-77. On Cricket has several essays on Indian batsmen (Tendulkar and Kohli among them) as well as an evocative portrait of Bishan Bedi, whose “bowling was all grace”, and who, off the field, “was and is a generous man”.

Reading Brearley’s book, I was educated and stimulated throughout. There were, however, two minor missteps. One was cricketing, when the author remarks that while Syed Kirmani was “excellent” in keeping to the great Indian spinners, “he hardly spent any time standing back”. (In fact, by taking so many superb catches off Kapil Dev, Kiri showed that Indians could keep capably to new-ball bowlers too.) A second was sociological, when an otherwise insightful chapter on the method and achievement of Muttiah Muralitharan does not mention that he was a member of the Tamil minority in Sri Lanka. Indeed, Murali’s greatest feats were achieved against the backdrop of a bloody civil war.

The non-or-trans-cricketing wisdom of Mike Brearley is particularly manifest in the essays on race. Consider this beautifully judged passage: “Of course hyper-sensitivity, a victim mentality, oversimplification and political correctness may become onerous and call for opposition. But the issue of racism is a deep and insidious blight in most if not all societies. We are right to get worked up about dismissing too carelessly the hurt caused. We should not turn a blind eye to flippant or casual racism. We correctly prioritize the damage of racist attitudes, and hold others and ourselves to account for assumptions of superiority or entitlement.”

These words apply equally to caste or gender prejudice, each of which is a deep and insidious blight on our own society. Assumptions of superiority and entitlement underlie the behaviour of so many upper-caste males in India. The damage this causes to human dignity is immense.

As a very young man, Brearley had accepted an invitation to tour South Africa with an MCC team and saw, at first hand, the indignities of the apartheid regime. Several years later, he joined David Sheppard — a former England captain and serving bishop, a man of conscience and of compassion — in the campaign to have the next MCC tour of South Africa cancelled because the South Africans would not admit a team with the non-white player, Basil D’Oliveira, in it.

David Sheppard is clearly one of Brearley’s heroes. “David was a kind and deeply thoughtful person”, he writes, “who helped people see what they had in common. He inspired love, and brought out the best in others. He was generous.” Of Sheppard’s work in the inner-city slums of Liverpool, Brearley comments: “He had to learn that listening was a form of giving, and he came to appreciate the need to be open to leadership qualities from within deprived communities. He realized that many ‘ordinary’ people were often more able to come alive and feel free in company or groups, than in one-to-ones. He saw the need for both sides of an argument between those stressing personal commitment to God and the individual soul, and those stressing the need for changes to the structures of society so that more individual souls have a chance.”

Mike Brearley is cut from the same cloth as David Sheppard; he, too, has thought deeply about morality and justice within the sphere of cricket and outside it. Of all the Test cricketers now alive, Brearley may be the wisest. Let me end, however, with an excerpt from his book that reflects the other side of his career; namely, the fact that, as a player, he was, as it were, less than great. In a discussion on the joys of fandom, Brearley writes: “[W]e become mini-Federers as we watch Roger play a cross-court forehand, or mini-Warnes when Shane bowls a perfect leg-break, or mini-Chappells when we see Greg play a back-foot stroke off his hips with sumptuous elegance. It’s not that we are under an illusion. We know we’re not Federer. But we enter the mind-set. We know they are beyond us, but just for a moment we have a sense of its possibility (or at least its imaginability).”

This is a passage that Viv Richards or Shane Warne could never have written; not just because they do not have the words, but because they were too good at what they did. Brearley knows what it is to fail on the field, with the bat and the gloves; and it is this experience of fallibility, as much as his own intelligence and range of experience outside sport, that underwrites this fine and stimulating book.