My first editor, Rukun Advani, once described himself as “a composite hybrid of the Indian and the Anglo-European,” who sought to reconcile “within himself those varying cultural influences which chauvinistic nationalists could only see as contradictions.” This self-characterisation I might avow as my own. One mark of the Anglo-European in me is that unlike members of the Swadeshi Jagran Manch, I had not just uncles and aunts, parents and grandparents, but also a godfather. It is this person I wish to write about here because the centenary of his birth falls this week and because being my godfather was the very least of his distinctions.

Born on October 6, 1923, K.T. Achaya was the son of an accomplished sericulturist who managed a silk farm run by the Government of India in Kollegal. The boy took his birthplace as his first name, though he was always known by his middle name, Thammu. He was one of my father’s oldest friends — which is how I became his godson. They first met as students at Presidency College in Madras where both studied Chemistry. They carried on to the Indian Institute of Science for their MSc, spending their off-lab hours cycling through the Mysore countryside. My father stayed at the IISc for his PhD, while Thammu Achaya took his doctorate in Liverpool. After his return to India, the friends resumed their friendship, which lasted till Thammu’s death in 2002.

Thammu Achaya was a food scientist, an expert on oilseeds. While they shared a background in science and happy college memories, my father and he had very different personalities. Thammu was a lifelong bachelor; my father had a gloriously happy marriage which lasted sixty years. My father did all his post-doctoral research in one place, the Forest Research Institute in Dehradun, whereas Thammu, after coming back from Liverpool, held scientific jobs in Hyderabad, Bombay, Mysore and Bangalore. My father had a tin ear; Thammu had a serious interest in classical music and time for jazz and blues too. My father loved language but not literature; that is why most of the books in our home in Dehradun were dictionaries. Thammu, however, read fiction and even some poetry.

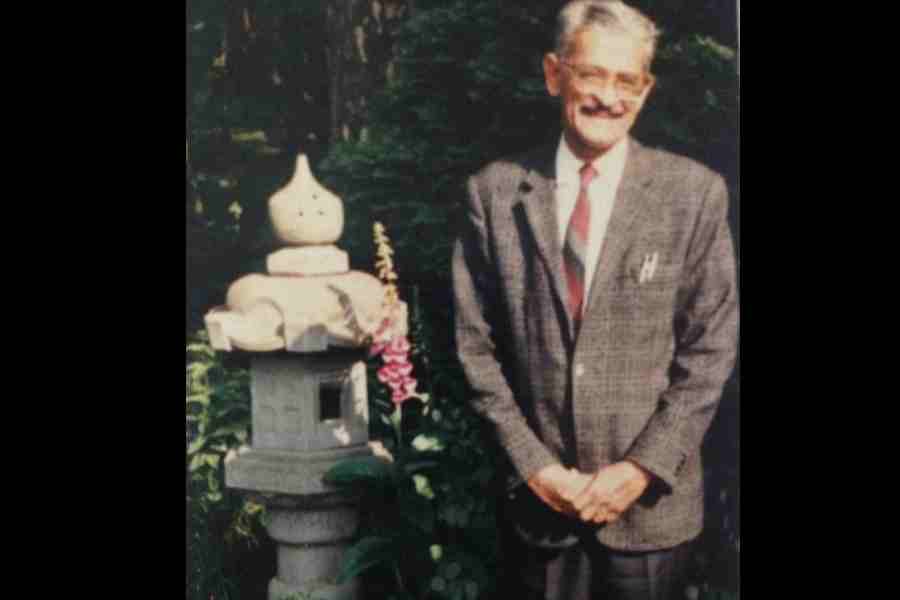

Thammu Achaya was a Kodava, born into a community of hillfolk that prides itself on its martial prowess and from whose ranks have come army officers, planters, shikaris and hockey players. Thammu’s brother was a forest officer, and two of his sisters were married to generals. As a scholar, reader, and music lover, my godfather was an altogether untypical Kodava. Because I was Guha’s son, he warmed to me; because (unlike Guha) I listened to music, he warmed to me even more. When I was a college student, he introduced me to Paul Robeson, playing “Joe Hill” for me on the gramophone when I visited him in his Bombay flat. However, I really got to know him well only in my thirties after he and my parents both came to settle in Bangalore. Through the 1980s and 1990s, I would go often to see him in his apartment in Indira Nagar where he lived amidst his books, his records, and his cats.

To me, his godson, Thammu was generous with his time, his possessions, and his encouragement. He gifted me some books I still possess, among them a signed first edition of S. Gopal’s superb biography of his father, the philosopher, S. Radhakrishnan. When I first began writing combative pieces in the press, and my middle-class, apolitical parents began to worry, he calmed them down while telling me: “Be fearless.”

In his person Thammu Achaya seamlessly combined Indian and Western culture, albeit at a higher level than either Rukun Advani or myself. He could appreciate the subtleties of Pattammal and Pavarotti, Baudelaire and Bharati, and of the best rasam and the finest red wine too. As a single man (he was gay, but, given the conservatism of the time, had to keep this behind wraps, though, to his credit, my father knew and did not disapprove), Dr Achaya had developed a passion for cooking. He had lived in different parts of India and the world and experimented with many different cuisines. This got him interested in food history, in how chillies came to the subcontinent, for example, in the origins of that South Indian staple food, the idli, in why even Mughal emperors liked to drink Gangajal.

After doing important work on protein chemistry, publishing papers with titles such as “Chemical Derivatives of Castor Oil”, in his retirement, Dr Achaya had started writing essays for a general audience. On one of my visits to his flat, in the year 1988, as I recall, he pulled out a sheaf of xeroxes to show me. These were a series of eighteen articles he had written on the history of Indian food for the journal, Science Age, edited by the fine (and now sadly forgotten) journalist, Surendr Jha, and published by the Nehru Centre in Bombay. Would I take these xeroxes home and read them, asked my godfather, and tell him whether they could be expanded into a book?

I took the material home and had a look. Then I called Thammumama and told him that the essays seemed interesting. But whether they would make a book only my friend, Rukun Advani, of the Oxford University Press, could say. Should I inform him about them? He said I could. I did, and soon afterwards Rukun Advani flew down to Bangalore. He met Dr Achaya and took the xeroxes back to Delhi. Soon, a contract was signed between my godfather and OUP, committing the latter to publishing a book expanding on his magazine articles. Such were the origins of what its editor was to call, in print, that “incomparable classic on Indian food for general readers, Indian Food: A Historical Companion.” Dr Achaya went on to publish two other major books with the OUP, titled A Historical Dictionary of Indian Food and The Food Industries of British India, respectively.

These books drew on a lifetime of research, reading, and experimentation. The sources consulted by Dr Achaya spanned a wide variety of scholarly disciplines and languages. A scientist with a deep interest in the humanities, he was himself fluent in Kannada, Tamil, English, Kodava, and Hindi and knew some Sanskrit, Urdu and Telugu too.

My Thammumama died in 2002, but his intellectual legacy lives on. A book I have recently read, Nandita Haksar’s The Flavours of Nationalism: Recipes for Love, Hate and Friendship (Speaking Tiger, 2018), has many appreciative references to his research. Of his documentation of food markets in ancient India which sold the flesh of many animals, the cow included, Haksar remarks: “Thank goodness K.T. Achaya is dead, otherwise he would be executed as an anti-national by the Hindu extremists.”

In a blog post on one of his death anniversaries, the Delhi-based writer, Marryam Reshii, remarked: “What the great Salim Ali is to Indian ornithology, Kollegal Thammu Achaya is to Indian culinary history.” She added: “He might not have personally trained or taught them, but for most food industry professionals, chefs, and food writers, Achaya remains an acharya.”

Neither Haksar nor Reshii knew the man in the flesh. Nor did that fine food historian and writer, Vikram Doctor, in whose columns the name of K.T. Achaya pops up more often than any other. Doctor says of Achaya’s literary legacy that “his work in documenting food references in a wide range of texts is so wide and comprehensive, it’s almost a default to start looking up what he has said on any food subject before starting.” Reading this, I puff up with pride, as his godson; while also feeling a sense of relief, for by directing Thammumama towards Rukun Advani I was able to indirectly discharge some of the debt I owed both men.

Let me end this tribute, however, by acknowledging another debt, to the person through whom I first got to know Thammu Achaya. I had long admired my father for his absolute disregard for religious and caste prejudice. Yet it was only after Thammumama’s death in 2002 that I came to appreciate my father’s radical progressivism in matters of individual sexual choice too. For this great protein scientist and greater food historian, this connoisseur of fine art, music, literature and dance, had to live his entire life in the closet, suppressing his sexuality from acquaintances, neighbours, and relatives, from his scientific colleagues, and from the world at large. Among the few sources of strength that Thammu Achaya had outside the then small, secretive and insecure community of gays in India was his old college friend, my extremely heterosexual father.

ramachandraguha@yahoo.in