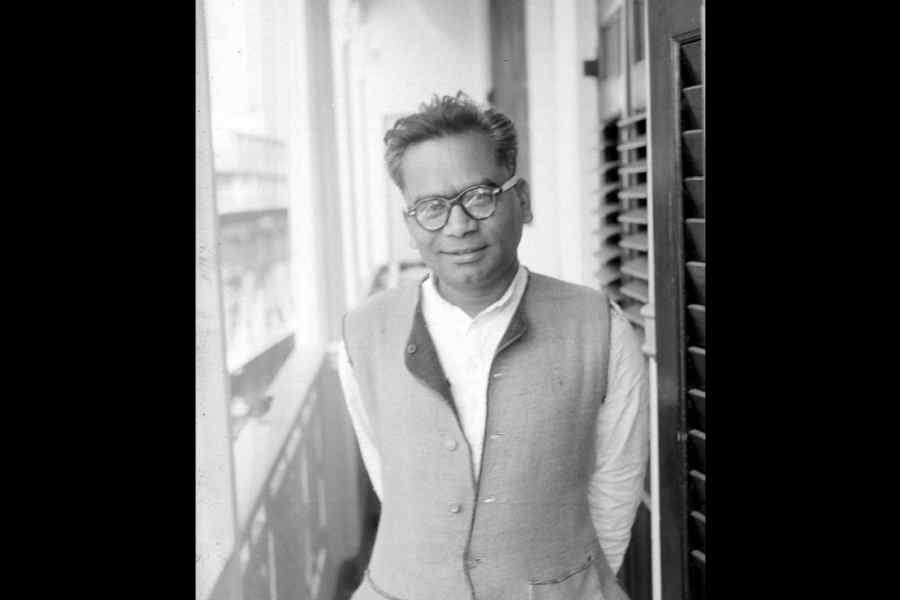

In the last decades of British rule in India, socialists and communists were active in anti-colonial politics. In the first decades of Independence, both groups were important challengers to the dominant Congress Party. Those early generations of socialists and communists were characterised by courage and idealism and had other virtues as well. Yet they shared one blind spot; a lack of awareness of the major form of discrimination in Indian society, that of caste. The one exception to this trend was the socialist thinker and politician, Rammanohar Lohia (1910-1967).

Lohia’s writings on caste were collected together in a book published in his lifetime by his admirers in Hyderabad. That book has long been out of print; but a revised version has been brought out by an independent publisher, coincidentally also based in Hyderabad.

Lohia accurately notes of his comrades on the Left that "many Socialists honestly but wrongly think that it is sufficient to strive for economic equality and caste inequality will vanish of itself as a consequence. They fail to comprehend economic inequality and caste inequality as twin demons, which have both to be killed."

Lohia himself was clear that "caste is the most overwhelming factor in Indian life. Those who deny it in principle also accept it in practice." The "great facts of life such as birth, death, marriage, feasts, and other rituals," he pointed out, "move within the frame of caste. Men belonging to the same caste assist one another at these decisive acts." As he further observed: "The system of castes is a terrifying force of stability and against change, a force that stabilises all current meanness, dishonour and lies." This system was defined and enforced through discrimination to ensure that the "high-castes… maintain their rule, both political and economic and, of course, religious. They cannot do it alone through the gun. They must instil a sense of inferiority into those whom they seek to govern and exploit."

Though Lohia does not ignore discrimination against Dalits (whom, using the language of the day, he calls "Harijans"), his focus is on the sharp division between the Savarna or Dvija upper castes, from whose ranks the political, administrative, professional, business and intellectual elite came, and the Sudra castes who were largely unrepresented in positions of power and authority. Writing in 1958, he observed that while the Savarnas constituted less than one-fifth of India’s population, "in respect of the top leadership of the four main departments of national activity, business, army, high civil services and political parties, the high-castes easily comprise four-fifths." This imbalance had to be corrected for the nation to progress. Lohia wanted his fellow socialists to lead the struggle "to pitchfork the five downgraded groups of society, women, Sudras, Harijans, Muslims and Adivasis, into positions of leadership, irrespective of their merit as it stands today. This merit is at present necessarily low. The tests of merit are also such as to favour the high-caste. What long ages of history have done must be undone by a crusade."

Lohia also urged socialists to promote inter-marriage across jatis and, especially, across varnas. As he wrote: "If the barriers of caste are broken or even loosened, many Dvija young men would be attracted to Sudra women, and bring happiness to themselves and the country. In a like manner, Sudra boys would also be able freely to enter the world of Dvija women. It is now essential that the Dvijas and the Sudras must not only understand to define caste as comprising of those capable of producing children of one another, but grasp the definition instinctively."

In 1960, Lohia called for the formation of an Association for the Study and Destruction of Caste. He outlined eight specific aims of this Association, of which let me single out two. First, that it "shall purify religion and its practices of the taints of caste, which shall while believing that intermarrying alone ultimately dissolves castes and propagating for it through scientific studies and the creative arts, concentrate on the immediately attainable aims of common and festival meals." Second, that it "shall demand the securing of sixty per cent of leadership posts in government, political parties, business and the armed services, by law or by convention, to the backward castes and groups namely women, Sudras, Harijans, Adivasis and the lower-castes among religious minorities taking care to see that the one or two numerically powerful backward groups do not usurp the rights of the immensely more massive but splintered totality of the lower-castes…"

One fascinating section of the book reproduces a series of letters exchanged in 1955-1956 between Dr Lohia and his colleagues on the one side and Dr Ambedkar on the other. The attempt here was to bring these two leaders and their followers closer together, perhaps with a view to their two parties fighting the 1957 general elections on a common platform.

The correspondence began with Lohia telling Ambedkar that "I very much wish that sympathy should be joined to anger and that you became a leader not alone of the scheduled castes, but also of the Indian people." Ambedkar wrote back asking Lohia to come to meet him in Delhi on October 2, 1956 (that this was Gandhi’s birthday was probably just a coincidence). Sadly, Lohia’s peripatetic life and Ambedkar’s ill-health prevented the two radical reformers from meeting in person to discuss their possible collaboration.

Ambedkar passed away on December 6, 1956. Lohia now wrote to his fellow socialist, Madhu Limaye, saying that "Dr. Ambedkar was to me, a great man in Indian politics, and apart from Gandhiji, as great as the greatest of caste Hindus. This fact had always given me solace and confidence that the caste system of Hinduism could one day be destroyed." He further remarked that "Dr. Ambedkar was learned, a man of integrity, courage and independence; he could be shown to the outside world as a symbol of upright India, but he was bitter and exclusive. He refused to become a leader of non-Harijans." Lohia thought the best tribute to Ambedkar was for his admirers to "continue to have the symbol of Dr. Ambedkar for homage and imitation, and Dr. Ambedkar with his independence but without his bitterness, a Dr. Ambedkar who would act so as to be a leader of all India and not Harijans only."

Lohia’s sharp awareness of caste discrimination marks him out from the other socialists of his day as does his feminism. He writes that, if "the Indian people are the saddest on earth," then the "two segregations of caste and woman are primarily responsible for this decline of the spirit." He notes that "these two segregations of caste and sex are interrelated and sustain each other."

Lohia wrote that, if, as was commonly held in patriarchal society, "a woman’s place is in the kitchen," then socialists should make the counter-claim that "the man’s place is in the nursery." Here he was, sixty and more years ago, arguing that husbands and fathers must participate equally in childcare, a noble ideal that (at least in India) is still honoured mostly in the breach.

The first article in this book is a blistering critique written in 1953 of the then president, Rajendra Prasad, washing the feet of Brahmins in Banaras. Of this act Lohia remarked that the president "has lost my respect and of many millions like me." For Lohia, caste and gender hierarchies were equally to be deplored. In the India of the 1950s, he found that "a black sadness prevails," for there is "no possibility of free conversation between the priestess and the shoemaker, the teacher and the laundress in a land, whose president bathes Brahmins' feet." Lohia was here advocating a spirit of fraternity in phrases and sentiments that would surely have been endorsed by Ambedkar himself.

The articles, letters and speeches quoted in this column were written between 1953 and 1961. It may be that Dwijas do not dominate politics and administration as completely as they did in the 1950s. Yet, in cultural and economic life, they continue to exercise an influence far out of proportion to their share in the population. In many respects, therefore, Lohia’s thoughts and words on caste have a strikingly contemporary ring.

ramachandraguha@yahoo.in