On the banks of the Hooghly, across an acre of land in West Bengal’s Uttarpara, sits Uttarpara Jaykrishna Public Library (UJPL), a group of buildings that serves as a jewel in the crown of Bengali and Indian heritage. UJPL’s Doric pillars and pilasters, hanging verandas, checkerboard floors and charming khorkhori windows all give it a stately and palatial character. Everything about the library, right from its address — 229 Grand Trunk Road — to its iron gates, seems memorable. To reach UJPL, Asia’s first free-circulating library, one must cross the Vivekananda Setu (Bally bridge) and Uttapara’s crowded streets. The sheer grandeur of the library’s regal premises makes this trip worth your while and effort.

Opened formally to the public as a free library on April 15, 1859, the UJPL was once a school and a resource centre for researchers. Founder Jaykrishna Mukherjee had a single aim — he wanted UJPL (first known as the Uttarpara Public Library) to give the region the best possible reading facilities. Inspired by the progressive beliefs of Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar, Mukherjee wanted to satiate the desire that Uttarpara’s residents had for education. After having set up many schools in the area, Mukherjee set up this library to further the Bengali Renaissance movement of the early 19th century. Charity, for him, always began at home.

Founder Jaykrishna Mukherjee’s bust at the library

With something for everyone

When Mukherjee began construction of the library in 1856, spending Rs 85,000 on the building and its garden, he was guided by Dwarkanath Tagore and the 1850 London Public Library Act. According to Sir William Hunter, who stayed here for three years, compiling his accounts of Bengal, the library was a “treasure house”. He called it “a unique storehouse of local literature, alike in English and vernacular tongues.” In 1855, Reverend James Long released his famed catalogue of Bengali Newspapers and Periodicals, using Mukherjee’s collection as his foundation. In 1866, Pandit Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar visited this library with the English educationist Mary Carpenter. Today, near the library’s main entrance, you can see the names of dignitaries who have visited the library over the years — Sir Edwin Arnold, the Marquis of Dufferin, Surendra Nath Banerjee, Bipin Pal, Kesab Sen and so on.

The guest room on the first floor where Michael Madhusudan Dutt stayed on two separate occasions

After returning from England, Michael Madhusudan Dutta was finding it hard to find a place to stay. It was Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar who requested Jaykrishna Mukherjee to make arrangements for Dutta to stay in the southwestern corner of the library building. The poet lived here on two occasions, in 1869 and in 1873. His room is still being maintained as a micro museum of sorts, along with a display of utensils and cutlery that have been used by distinguished guests over time. The library’s lawn is also immortal for many. It was here that Sri Aurobindo gave his first speech after his release from prison in May 1909. It is said that nearly 10,000 people were here on that day, listening to the soft-spoken leader in pin-drop silence. A plaque on one side of the garden today commemorates that hard-to-forget event.

A display of utensils and cutlery that have been used by distinguished guests over time

UJPL’s present collection of over 55,000 rare books and periodicals is as enviable as it is priceless. You can, for instance, find here a copy of Michael Madhusudan Dutta’s book, Hectorbadh Kavya, and also copies of Dikdarshan, one of India’s earliest periodicals. Published in Serampore, the first Bengali printed books can all be found here. For those looking for 17th, 18th, and 19th century publications, UJPL is a veritable gold mine. Some of the periodicals and letters at UJPL would be hard to find elsewhere, even in the British Museum. For many, the UJPL catalogue is richer than London’s India Office Library.

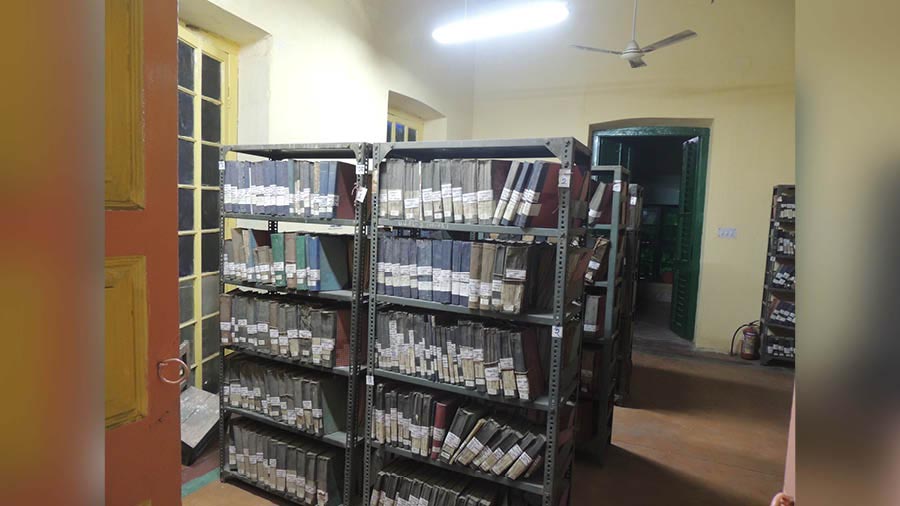

UJPL’s present collection of over 55,000 rare books and periodicals is as enviable as it is priceless

From Digdarshan, the first Bengali periodical, the Bengal Chronicle of 1821 and the Calcutta Monthly Journal of 1798 to books by William Carey, John Clark Marshman, Walter Walsh, Nathaniel Brassey Halhade, Raja Ram Mohun Roy and Mohanprasad Tagore, UJP, it would seem, has it all. Here you can also find a Sanskrit translation of the Holy Bible, the letters of Max Muller, as well as rare government reports, charters, treaties and confidential state secrets. Added to this, UJPL also houses more than 200 leaf and paper manuscripts that have been collected from places like Varanasi and Kashmir, and even far-off Tibetan monasteries. Many renowned personalities, including Jaykrishna Mukherjee, have donated their life’s collections to this library.

A treasure trove of calm

UJPL’s GT Road address can be misleading. The calm and quiet of the river-facing library seems completely at odds with the hubbub of the busy highway. The oldest building on the premises, the one Mukherjee had built, is today UJPL’s research wing. This is where you will find its collection of rare books and periodicals. After the West Bengal government took control of UJPL’s running in 1964, it took over a nearby house that once belonged to a zamindar. The first floor of this annexed building today serves as UJPL’s reading and textbook section, while its ground floor is where books are lent. UJPL’s newest building, one that was constructed to commemorate its 150 years, houses the library’s section for children.

UJPL’s GT Road address can be misleading. The calm and quiet of the river-facing library seems completely at odds with the hubbub of the busy highway

Hooghly’s District Library Officer, Indrajit Pan, doubles up as UJPL’s librarian-in-charge. Pan’s task is cut out. Not only does he have to look after the library’s rare collection, he is also responsible for managing UJPL’s many visitors. The library has more than 5,000 lending members. Another 13,000 or so come here either to read or for career guidance.

Librarian Arpita Chakraborty manages the day-to-day activities of UJPL. Chakraborty, a technical assistant, told My Kolkata that she venerates this space the way she does her parents. “Each time I set foot on this ground, I consider it a special honour,” she says. “Despite being a government employee, I wish I could have my way and continue working here. I cannot think of working in any other place. I don’t know if it is the sight of the river, but there is something very special about this calm building and the treasures it shelters.”

![‘I cannot think of working in any other place. I don’t know if it is the sight of the river, but there is something very special about this building and [its] treasures.’ said librarian Arpita Chakraborty](https://assets.telegraphindia.com/telegraph/2023/Apr/1681212297_the-main-guest-room-of-the-library-seen-from-the-balcony-4.jpg)

‘I cannot think of working in any other place. I don’t know if it is the sight of the river, but there is something very special about this building and [its] treasures.’ said librarian Arpita Chakraborty

UJPL today offers students and researchers Wi-Fi services and air-conditioned rooms. Since the library is run by the state government, all its services — everything from lending books to career guidance — can still be availed of for free. Though the library computerised its operations in 2004, it has not altogether forsaken traditional manual methods. In a sense, UJPL lives in both the past and the present, but what remains precarious is its future.

Perils of the present

The modern amenities of UJPL are sadly never able to fully disguise the entropy that some of its sections have submitted to. As time passes, a lot of the library’s irreplaceable editions are gradually decaying or simply crumbling. Though crippled by a paucity of funds, inadequate infrastructure and a dearth of personnel, UJPL, it must be said, is no stranger to hardship. In 1964, for instance, the West Bengal government had taken over the library only after the residents of Uttarpara had insisted that UJPL be preserved as a symbol of their local heritage.

The funds that the state government had allocated for UJPL in 1964 were minimal. They only ensured a limited upkeep of the premises. Even though the allotted funds had risen substantially by 1997-98, they still fell short. A library as old and vast as UJPL required more investment. Bidhan Chandra Roy, chief Minister of West Bengal from 1948 to 1962, had been honest enough to accept that any state government would find it hard to manage such a huge library. Like other chief ministers after him, Roy, too, had asked the central government for funds and assistance, but the library never seemed to receive the attention it deserves.

Racks laden with treasures of the past — long awaiting administrative care

Only when Pranab Mukherjee was the country’s finance minister from 2009 to 2012, could one see light at the end of the tunnel. Led by Santoshir Chattopadhay and Mukherjee’s sister, librarian Swagata Das Mukherjee, a campaign for giving UJPL national heritage status was finally showing signs of bearing fruit. The matter came to be discussed in the zero hours of Parliament. After several deliberations, the Centre wanted to know what West Bengal could do for the library, but the state government threw its hands in the air and the issue lost steam.

The governmental impasse between state and Centre has only worsened some of UJPL’s woes. Seeing the continuing popularity of the library, it today seems imperative that its collection should widen and that its already existing collection of rare books and periodicals be scientifically preserved. UJPL desperately needs its complete bibliography to be catalogued by trained and efficient librarians. Despite administrative neglect and bureaucratic red-taped apathy, it seems heartening to see that UJPL has continued to be a valuable resource for several researchers, scholars and students over the years. Given the antiquity of its records, the Centre ought to declare the library an ‘Institute of National Importance’. Everything about it — its books, its architecture — deserves relief and acknowledgement.

The library today lacks specialised staff and infrastructure, and is desperately yearning for more attention

Almost half of UJPL’s collection has not been explored recently. In order to make these texts readily available again, the library needs to be indexed and arranged more systematically. These efforts can only be bolstered by an influx of funds. As an ‘A grade’ library, UJPL must be accorded the same amount that is given to its counterparts. The library today lacks specialised staff and infrastructure, and is desperately yearning for more attention.

After UJPL was computerised in 2004, several of its possessions were digitised but this project was later discontinued. With that first database now inaccessible, the library has lost its opportunity to become an unprecedented digital reservoir of history and information. For UJPL to again attract new members, it needs an online footprint. It is essential that its contents be digitised. The library also wants to make efforts to deliver books to the elderly.

With barely any kids on its roster, UJPL’s children’s section is in sore need of a revival. The library ought to be given the money it needs to reimagine this wing. The interventions could be unconventional and unique. Additionally, it is time a full-fledged museum came up here.

One man’s dream for Uttarpara

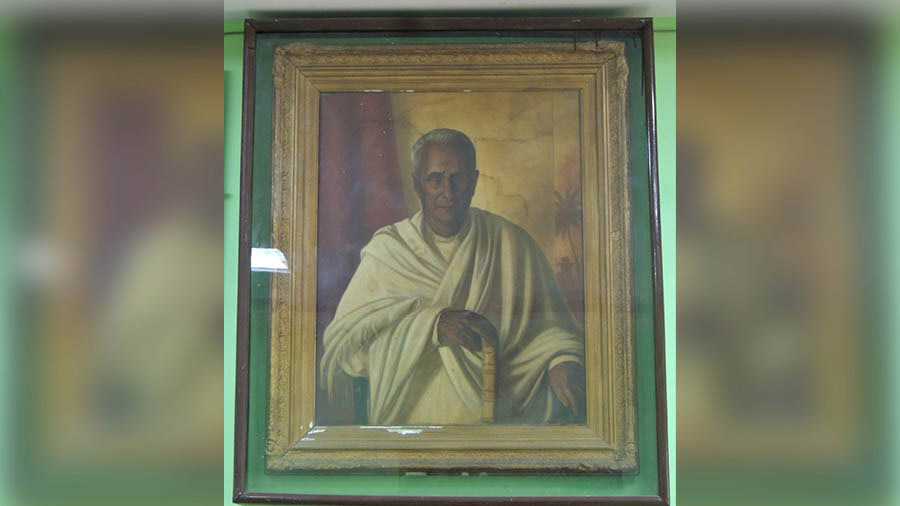

Founder Jaykrishna Mukherjee’s portrait at the library. After opening of the country’s first free lending library in 1859, Mukherjee’s philanthropy continued till 1888, the year he passed away

If asked to justify its historical authenticity, UJPL would not have to do much. The biography of its founder Jaykrishna Mukherjee, for instance, seems proof in and of itself. Born on August 24, 1808, in Uttarpara, Mukherjee was first educated at a local pathshala and then in an English-medium school. Well versed in Urdu and basic Persian, Mukherjee was known for his keen intelligence and his ability to solve problems. An upright and skilful accountant, he took on multiple roles during the British Raj. Around 1832-33, Mukherjee emerged as an important land owner, and his status in the area soon nudged him toward a more public life.

Wanting to improve the educational standards of his people, Mukherjee saw no difference between boys and girls. After realising the benefits of self-governance, Mukherjee set up the Tattvabodhini Pathshala in 1840. He also initiated and executed many beneficial works in Uttarpara — the commissioning of roads and bridges, healthcare, sanitation and so on.

In 1854 itself, Mukherjee had submitted a proposal for a public library in Uttarpara to the divisional commissioner of Burdwan, but when he was turned down, he decided to take matters into his own hands. After opening of the country’s first free lending library in 1859, Mukherjee’s philanthropy continued till 1888, the year he passed away.

Another view of the library’s grounds and facade

After Mukherjee’s death, UJPL was looked after by his sons. Though they first used their father’s principles and vision as their foundation, age-old property feuds eventually made the maintenance of the library difficult in 1964. One reason for this was the end of the zamindari system. At one point, the Mukherjees used the taxes they collected from Uttarpara’s people to foot the library’s expenses. This even included the cost of food for readers and visitors.

In its mention of Uttarpara, the Encyclopaedia Britannica says, “Uttarpara is famous for the Public Library founded and endowed by Jaikissen Mukherjee, which is specially rich in the books of local topography.” Even though Britannica misspells Mukherjee’s first name, the nod that it gives to UJPL seems significant. Tales of its treasures appear to have travelled far and wide. Though the library is ailing today, it still stands testament to the initiatives of a single man who wanted both Uttarpara and Bengal to be progressive, modern and educated.