Nestled in the Maikal range of Satpuras in Madhya Pradesh, Kanha National Park is India’s pre-eminent tiger reserve, and globally acclaimed as one of the finest wildlife zones in the world.

Straddling the districts of Mandala and Kalaghat, Kanha was first declared a reserve forest way back in 1879, became a wildlife sanctuary in1933 and was finally listed as a national park in 1955. “Our forest is known for its tigers, but ever since I have made Bagh Villas as my base, the sheer biodiversity of this ancient forest has fascinated me to no end,” says Shrikant, one of the five naturalists at the sustainability-focused Bagh Villas and our guide for the afternoon safari.

Guided nature walks are organised by Bagh Villas

We drive into the somnolent setting of the primeval forest. This is early-March, and the dry deciduous jungle is laced with post-winter earthy shades of green but the towering cotton and palash trees have brought in vivacious hues of fiery red into the canvas. The mid-afternoon sun filters through the overhead canopy to illuminate the brick-coloured tract strewn with fragrant sal flowers and wilted leaves.

A family of bovines by a water body inside the Mukki range of Kanha forest

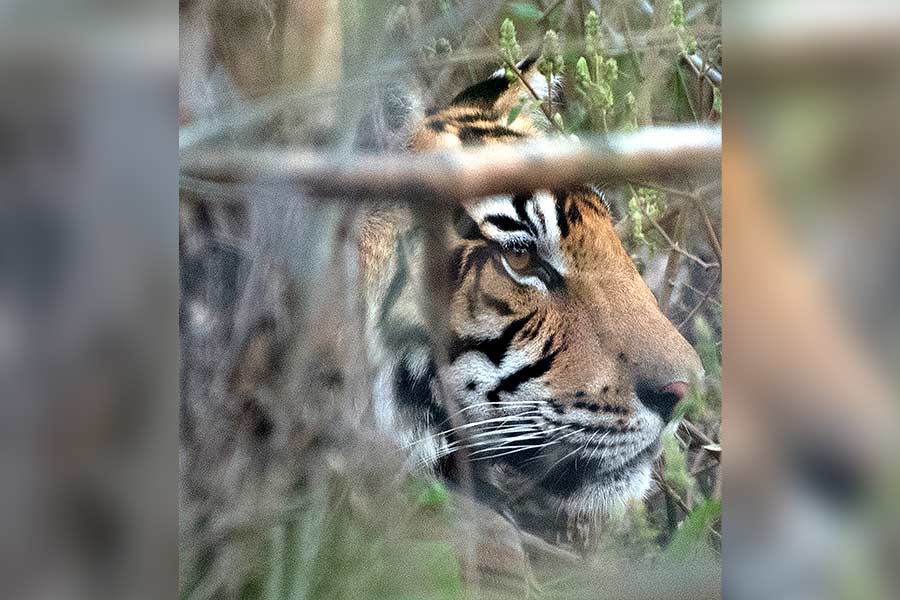

A Maruti Gypsy overtakes us and takes a sharp right turn. Shrikant instructs our driver to follow suit and answers our collective queries with a cryptic word under his breath: “Tiger”. We fall silent as our 4WD (four-wheel-drive) vehicle revs up and steers ahead amid a swirl of red-brown dust. A few hundred metres ahead, we spot three vehicles parked near a small clearing with patches of undergrowth hemmed by thick bamboo groves. Shrikant hands me his binoculars and silently points to a bush, half-concealed by a bamboo thicket. And they immediately come into view.

Deer, deer!

Two sub-adult males, playfully pouncing and climbing on each other, practising the skills they will need to survive as adult hunters. The mock wrestling match of the siblings poses ample opportunities to the shutterbugs among the motley group of fascinated onlookers before the duo decide to leave the scene, trotting their way in a majestic gait, paying scant regard to the vehicles and the incessant sound of shutters.

“At Bagh Villas, our primary focus has always been a minimal carbon footprint with our sustainability-focused initiatives, homegrown produce and solar power panels. The jungle safaris and in-house amenities are designed so as not to leave any traces on this ancient forested land,” Akhilesh Nair tells me over an elaborate spread later that evening.

The king, waiting in the wings

His wife, Lia, is from Indonesia and with a background in hospitality industry, she curates the culinary experiences at Bagh Villas, blending regional delicacies with contemporary international cuisine. “We source almost all of our vegetables and leafy greens from our kitchen garden and the meat and dairy come from the villages around us,” she tells me.

After a restful night at one of the tented suites, I gear myself up for another foray into the recesses of Kanha National Park. Thin wisps of mist hover over the grassy flatland that rolls out in front of us as we set out to explore another zone of Kanha. It is a windy, cloudy morning and Laxmi, a forest guard, is accompanying us on this safari. She hails from the local Gond tribe. Kanha is the first national park in India to launch an initiative to encourage women to work as naturalists and set up a dedicated training programme for women to work in wildlife tourism in India.

A curated Italian lunch is often the culinary highlight of a stay at Bagh Villas

This morning, the jungle sports a sombre look under a dark grey sky and the woods turn gloomy and mysterious, yet seems to hold promises of an unforeseen adventure. Usual sightings of sambar, swamp deer and gaur zoom by but Shrikant does not seem too keen to make stops for them. After about half an hour, Laxmi signals our driver to stop the vehicle. Her weather-beaten face is taut with suppressed excitement. As the engine purrs to a dead stop, an eerie silence engulfs us, barring the occasional, sharp tweets of a parakeet.

Shrikant gives me a nudge and I follow his gaze to the upper branches of a large Arjun tree on the left of the forest tract. I keep my eyes peeled through the field glasses but for several seconds I see nothing but the dark green contours of foliage. And then a pair of yellow-green eyes pop into focus and I can trace the sleek, spotted, muscly stature of a leopard, stretched across a thick branch. “It’s a female, and she wants a good vantage view of a possible prey from up there,” Laxmi enlightens me. The feline beauty seems very relaxed but her eyes remain alert.

Inside the lakeside cottage of the resort

Another vehicle sidles up behind us. Excited whispers and camera clicks follow. The leopardess seems a bit ruffled with all this sudden attention. She sits up, stretches languidly and then in a flash she is gone, leaping down from the high branch, at least 25 feet above the ground.

“Now that’s a rare sighting,” Laxmi slowly breathes out her words, and adds that in her four years of experience as a forest guard in Kanha, this is only the third time she has spotted a leopard, one of the most elusive predators of the world.