Chances are that unless you’re a serious student of Kolkata’s colonial history or a regular visitor to the city’s historic churches, you would never have heard of Bishop Reginald Heber.

Bishop Heber was Kolkata’s second bishop, following Thomas Middleton who was the first. When Middleton died suddenly of sunstroke (he is buried under the altar of St. John’s church), Heber made the long journey from England to Kolkata and spent four action-packed years here, before his own untimely death in 1827 in Trichy where he lies buried. It is a sad fact that each of the first seven bishops of Calcutta had died while in office.

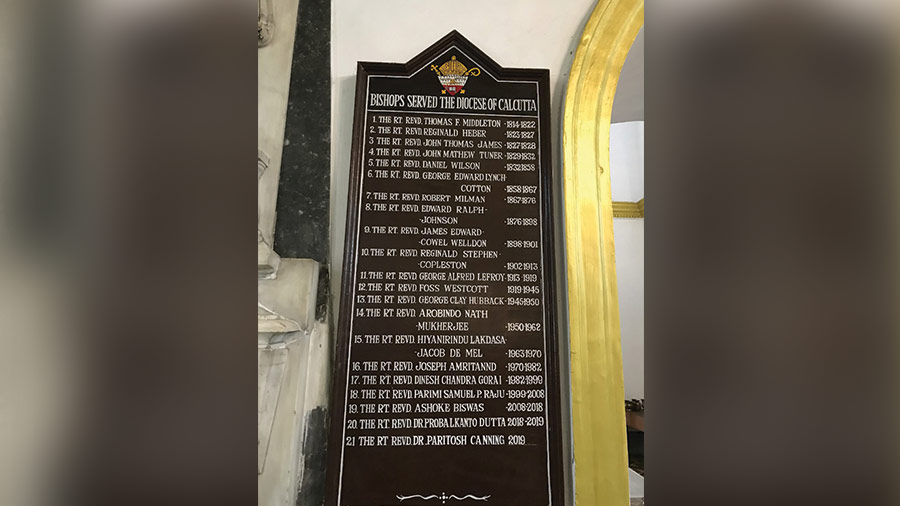

Second from top; Bishop Reginald Heber has pride of place as Kolkata’s second Bishop

Given Heber’s stature, it’s strange that he is almost forgotten in Kolkata. While Middleton is buried in the city, Heber’s memory has faded. This is probably because at the time, the newly formed diocese of Kolkata had also covered the territories of Bangladesh and Sri Lanka and right up to Australia, which led to Heber travelling extensively through India and eventually dying in faraway Trichy in the south. As a result, there are numerous schools and colleges honoring Heber in Tamil Nadu instead.

How I discovered Heber in a rural corner of England

The first I heard of Reginald Heber and his connections with Kolkata was when I was in the rural parish of Shropshire in England, researching the back story of Robert Clive (or Clive of India, another man with strong Kolkata connections). I was visiting the small town of Market Drayton where Clive was born and had spent his unruly teenage years before being shipped off to India, and my friends suggested that I also go to the adjoining village of Hodnet, which too had a Kolkata connection being the home of the Heber family.

The black-and-white Tudor style houses of village Hodnet, home to the Heber family

Hodnet was a pretty village sprinkled with Tudor-style black-and-white houses as if time had stood still. At the village’s St Luke’s Church, I was introduced for the first time to Bishop Heber, who had been the much-admired parish priest there for a long 16 years before leaving for Kolkata, never to come back.

The Hebers were still big in Hodnet, owning most of the village, including the pub where I was staying. Bishop Heber’s direct descendant, Sir Algernon Heber-Percy, was now the Lord of the Manor and patron of the church, and I was told that the church was a must-see because of its connections with Kolkata.

Leaving the comforts of home and family for “strangers in a strange land”

Reginald Heber was an Oxford-educated man of letters, known to be a poet and a thinker. When he was first offered the bishopric of (then) Calcutta upon the death of Middleton, he had refused the offer, concerned about the effect India’s climate may have on the health of his infant daughter Emily. Reginald and his wife Amelia agonised for days over the decision, consulting a host of local doctors for advice before finally taking the plunge and “accepting the offer gratefully”.

The tower-like façade of Hodnet’s St. Luke’s Church; where Bishop Heber was parish priest for16 years before leaving for India, never to return

What made Heber leave his familiar surroundings for India? Being financially well-off at home, it was clearly not the salary of “£5000 per annum and a retiring pension of £1500” that attracted him, which as his offer letter pointed out could not “compensate you for quitting the situation and comforts you now enjoy”. Heber, in his farewell notes to friends in Hodnet, mentions a “lurking fondness for all which belongs to India and Asia” and the chance to distinguish himself in an “unbounded opportunity for professional utility”. This interest in India later became apparent in the way Heber conducted himself once he got here, but more of that later.

The legend of Bishop Heber’s famous blue tiles

I stepped into St. Luke’s Church’s slightly musty interiors, guided by Chris Ashley, a local history buff showing me around. Together we unlocked the wrought-iron doors to the Heber chapel — its keys had been left dangling on a hook by its side — where many of the Heber family members rested. I saw the pulpit where Reginald Heber preached his final sermon at Hodnet, bidding farewell to the parish he had served for so long. And then I was shown the church’s biggest mystery, it’s two unique blue tiles.

All of the floor tiles at St. Luke’s Church had the same pattern, apart from two special tiles placed close to the altar. These two had a different design; of a distinctive bishop’s mitre (the ceremonial headdress of a bishop) with the initials “Rh” — for Reginald Heber — inscribed. It’s believed that these tiles were originally from St. John’s Church in Kolkata, which is where Bishop Heber preached his sermons in India, and had been brought here from Kolkata in recognition of Heber.

Look closely now; the two tiles at the bottom with a bishop’s hat and “R h” engraved on them…legend says, all the way from St. John’s Church in Kolkata

Could this be true? It had certainly piqued my curiosity. Sitting on the silent wooden pews of St. Luke’s Church in Hodnet, I resolved that when I got back to Kolkata I would try and find out.

Heber voyages to Kolkata

Heber left England for Kolkata in June 1823 and used the four-month sea voyage to teach himself Persian and Hindi, even beginning letters home with a Persian proverb he liked “a letter is half a meeting”. Once in Kolkata, he plunged quickly into ecclesiastical work including the affairs of the Bishop’s College, which was the brainchild of Middleton but was struggling now for leadership.

Though the East India Company was active in India through the 1700s, it was only from 1813 onwards that Christian missionaries were allowed to preach in the company’s territories. Before this, the company’s directors blocked religious activity fearing it would distract from the focus on trade and profit. Middleton, when he became Kolkata’s first bishop, believed there was need for a Bishop’s College near the city for preparing natives to be future preachers as well as provide broader education in English and the classics for the translation of scriptures into local languages.

Warren Hastings, the then Governor-General, had granted land for the Bishop’s College at Shibpur on the opposite bank of the (yet un-bridged) Hooghly, considered suitable both for its seclusion as well as proximity to Calcutta. Unfortunately, though Middleton set the wheels in motion, he died before the college was complete and it was left to Heber to progress it; to hire the professors, receive the first students (by the time of Heber’s death in 1826 the college had 10 students), ensure that scholarships were granted for free studies. Today, the original buildings of Bishop’s College still exist in Shibpur as The Indian Institute of Science, while Bishop’s College itself was shifted to its present location on Lower Circular Road.

The Bishop leaves Calcutta

After six months of finding his feet in Calcutta, Heber set out on his extensive travels, a feature that defined the four years he spent in India. He describes leaving Calcutta in the heat of June, rowing up the Ganga in a boat accompanied by “two smaller boats of very rude construction with thatched cabins”; one a cooking vessel and the other for luggage, and attended to by a retinue of over 30 boatmen and servants.

His journeys would take him across the country, from Benaras to Meerut to Bombay to Madras, and everywhere he earnestly documented the struggles of the locals along with his ideas for improving their lot. Heber argued for more magistrates for better governance (“…the entire civil and criminal jurisdiction of a district larger than most English counties…is entrusted to one young man”), replacing Persian with Hindustani for greater understanding of justice in the courts, more funds spent on roads and serais for ease of travel and he criticised the East India Company for over-taxing locals, arguing for the administration to pass to the British crown instead.

On the way, he visited Delhi and met the Mughal emperor; referring to Delhi as “a wealthy and flourishing town, with an orderly and industrious population, with conspicuously fewer beggars and fewer crimes than any other large city in India”, but with the Great Moghul himself living in a palace “…though dismally dirty and ruinous, is still very fine, and its owner is himself a fine and interesting ruin…his manner extremely courteous”*

All of this was a far cry from the quaint ways of Hodnet but Heber thrived in his new surroundings, genuinely enjoying fresh discoveries and his self-appointed role of pointing out mistreatment. His story came to an end at Trichinopoly (present-day Tiruchirappalli) in the south of India, on April 3 1826, where after a typically strenuous day of performing service, examining a school and addressing poor Christians, Heber retired for a cold bath to shake off his exhaustion and was found dead by his alarmed servant.

Heber’s funeral was held the next day in Trichy itself, his body interred in a grave at Trichy’s St. John’s Church, where a mural marks the memory of “Reginald Heber, Lord Bishop of Calcutta, who was here suddenly called to his eternal rest, during his visitation of the southern provinces of his extensive diocese”.

Not a blue tile in sight at Kolkata’s St. John’s Church

And what of the blue tiles?

Alas, my quest for Bishop Heber’s blue church tiles went in vain. I dug into all I could find on where Bishop Heber preached and lived in Kolkata, visiting historic churches and residences associated with him, but drew a blank.

I called on St. John’s Church, where Heber delivered his sermons and his name is prominently displayed as the second bishop, after Middleton. Explaining the story of the blue Hodnet tiles to Reverend Pradip Nanda, the present vicar, we scoured the church but returned empty-handed.

I visited Loreto House, entering the impressive mansion-like home that hosts the offices of the Loreto nuns. The nuns have been established here since 1841, but prior to that the previous occupants were Henry Vansittart (Bengal Governor in the 1760s), Sir Elijah Impey (the first Chief Justice of Calcutta’s Supreme Court and friend of Warren Hastings) and Bishop Heber during his brief stint in Calcutta. An iconic spiral staircase still survives from when the house was originally built, and perhaps Heber climbed them daily when he lived here, but there was no sign of blue tiles.

Loreto House’s original swirling staircase still survives, but no sign of the Hodnet tiles

So my feature on Bishop Heber remains strangely unfinished. I came across a story which connects different eras from colonial to now, varied churches in diverse lands, and links the people of a small village in rural England with the bustling metropolis of Kolkata. But no closure on the missing church tiles.

Adil Ahmad is a Kolkata-born discoverer deeply curious about the city’s heritage and history.