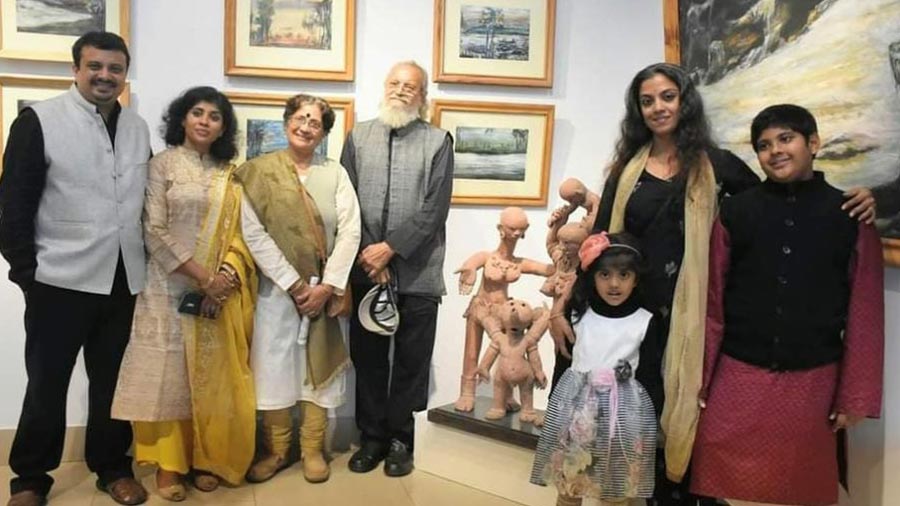

Though Brahmapur’s Charunagar seems like an ordinary Kolkata neighbourhood at first glance, one building here clearly stands out. The Garai Art Centre is more than a sum of its parts. It is a workshop and institution, yes, but it is also a love letter to the arts. Every corner of this space seems to have been touched by the genius of its residents. The Garais have been artists for two generations. Tarak Garai is a renowned sculptor, and his wife, Minakshi Garai, both paints and teaches. Indranil, their son, runs his own architectural sculpting firm in Pune and Bangalore, while their daughter, Shashwati Garai Ghosh, is an Odissi exponent and teacher.

The minute you enter the Garai Art Centre, you feel you can hear a chorus of artistic voices. Much of the courtyard now doubles up as Shashwati’s dance studio. Tarak’s massive workshop has taken over most of the garage. The walls are adorned by Tarak and Indranil’s sculptures. The paintings are all Tarak’s and Minakshi’s. “Every piece of art in this house is by Ma or Baba. There is no work in this house by any other artist,” says Shashwati.

All roads lead to art

Tarak spends roughly 10 hours every day in his workshop.

Though Tarak, 80, and Minakshi, 75, came from backgrounds that weren’t very artistic, their creativity finally found a way of making itself manifest. Tarak tells us he was born in Ghidaha, a remote village in West Bengal’s Birbhum District. “The Ajay River flowed beside our house, and as a kid, I would make thakurs (idols) out of sand. I still remember how the villagers would gather around and say, ‘Oi dyakh, Tarak ki korchhe!’ (Look at what Tarak is doing!’) Their encouragement gave me a lot of motivation. But all that was for pure joy. I didn’t even know one could do higher studies in art, let alone make a living from it.”

Tarak first began pursuing art in Class VI, a time when he had begun travelling to a new school on the other side of the river, some seven kilometres from Burdwan. “The headmaster told me I should go to art school, but my father felt the arts were solely for leisure. My family insisted I get a bachelor’s degree instead.” Thankfully, a teacher from Tarak’s school urged him to fulfil his dream, and his father, too, relented. “He would pay for my education at Kala Bhavana, Visva-Bharati, but I could take no help from him after graduating.”

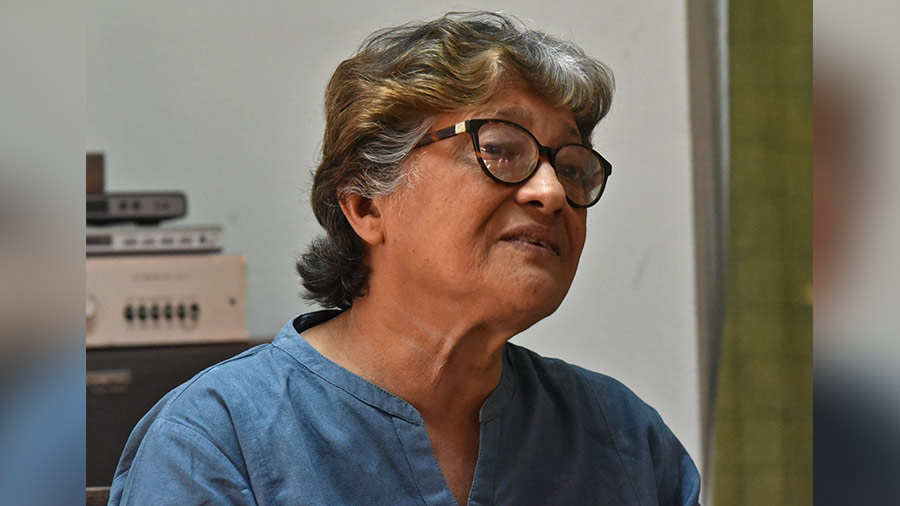

Minakshi operates the Minakshi Garai Art Circle above Tarak’s workshop, conducting both physical and virtual classes in painting

Minakshi’s father, similarly, worked in a bank. She says, “I was interested in art from my early days at St. Mary's Convent School, and the interest only grew when I began high school at South Point. I naturally took to craft, and made paintings for all the school exhibitions. In our generation, no one considered art to be a viable profession. We did it for pure love.”

Tarak and Minakshi met at Kala Bhavana. Telling us about how Santiniketan had had a “very profound impact” on him, Tarak says, “It was here that I met my mentor, Ramkinkar Baij. All our teachers were crucial in our journey. Sarbari Roy Choudhury, for instance, was the one who asked me to not return home, insisting I move to Kolkata instead.” Minakshi, who was one year Tarak’s junior, adds that she was fascinated by the young sculptor’s work because of its scale. “He never did small work. Everything had to be huge. In fact, even when he is buying vegetables, they need to be huge,” she laughs. “But I also noticed how he was different from other students, always engrossed in his work.”

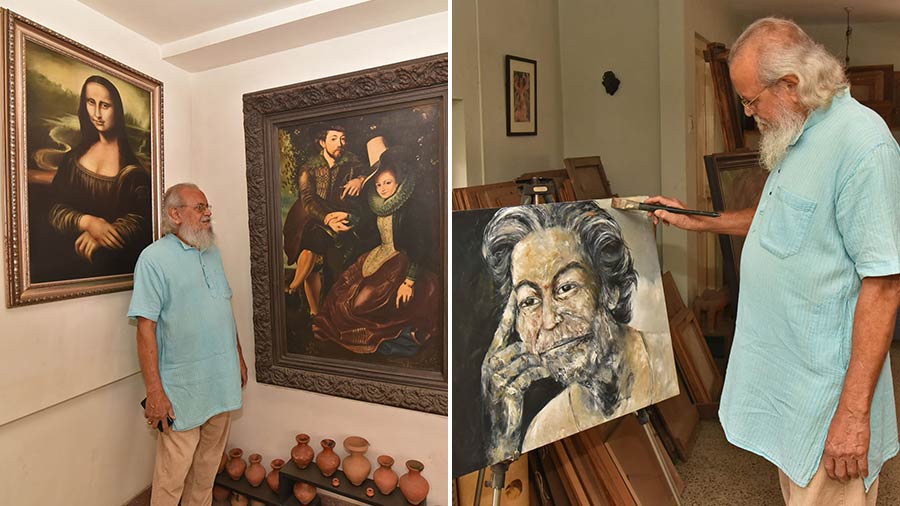

Tarak sold over 300 of his paintings to support the family during a financial crunch. He is currently putting the finishing touches to (right) a portrait of his mentor, Ramkinkar Baij

Though Tarak and Minakshi had enough common interests to be a suitable match, they faced much familial opposition. “We came from very different families,” says Minakshi, “but it all worked out in the end.” Two years after Minakshi graduated in 1973, the two were married. Tarak says, “Sarbari Roy Choudhury wrote a letter to his friend who had an interior decoration firm. He got me my first job, with a monthly salary of Rs 270 in 1972.” Minakshi, on the other hand, joined Julien Day School in Bhowanipore as a teacher while still in college.

With both Tarak and Minakshi holding steady jobs, life felt secure. Two years after their marriage, Tarak’s monthly salary went up from Rs 270 to Rs 1,000, but he still wanted something more from life. “I didn’t like the job. Feeling that this couldn’t be my entire life, I left.” The couple then used some of their original designs to set up a sari-printing business in Kolkata. As he recalls the mammoth scale of the business, a faint smile lingers on Tarak’s face, but then, suddenly, he looks downcast. “One morning, we got news of a major theft in our Kankulia shop,” says Minakshi. “Tarak immediately rushed there, but he came back dejected. He told us everything from the machine to the products had all gone. It was 1976 and we were broke. We didn’t have any savings, but we started again from scratch.”

'I have never done any commissioned work'

After they set up an interior decoration firm, Tarak also began selling his original paintings. “The business ran extremely well and we worked day and night to cater to huge clients,” he says. “I also sold over 300 of my paintings to support the family, but I had this innate desire to work on sculptures.” His life took a drastic turn in 1984, when Lalit Kala Akademi opened its doors in Golpark. “I paid all my labourers a month’s salary in advance. I shut down the business and sought admission at Lalit Kala. From that day, I have never done any commissioned work. I have only worked to nurture my own artistic voice,” says Tarak.

Tarak’s dedication to art seemed to pay off almost immediately. Within a month of his switch, he had made a huge wooden sculpture of Mahishasura, which the National Art Gallery bought for Rs 50,000. “That gave me more joy and creative fulfilment than orders worth lakhs I had bagged in my interior decoration days. As I kept working, I saw pieces that I sold for Rs 15 lakh being auctioned for crores, giving me even more validation. I sold a lot of my work, but I have stopped doing so in the last 20 years. Now I just preserve it.”

Shashwati’s biggest struggle in life was if she should choose visual arts because of her parents, or the performing arts because of her passion

The inheritance of art

It was perhaps inevitable that the two Garai children would also gravitate toward the arts. “Art was so normal in the family that for half my childhood, I thought everyone’s parents were artists,” laughs Shashwati, 42. “We would spend half our time at Lalit Kala, especially when there was no school. Our parents only told us one thing: ‘Do whatever you want in life, but do it with honesty, even if it’s opening a tea shop!’” Indranil, 46, later goes on to add, “I always say I was born with a ball of clay in my mouth. The Garai house is a house full of crazy people. I, too, have fond memories of visiting Baba at Lalit Kala, and engaging with both the art and artists there. I have grown up around sculptures. This is all I know.”

Minakshi tells us that Indranil initially wanted to study biology and become a doctor, but that, ultimately, he found his way to art. She says, “It didn’t take long for Indranil to say ‘I can’t do this!’ He wanted to be an artist like his baba.” Just like his parents, Indranil also joined Kala Bhavana after school. Shashwati, for her part, had a different conundrum. “I made a lot of paintings with Ma and sculptures with Baba, but due to my love for dance, my biggest problem was this: Should I choose the visual or the performing arts?”

Minakshi then narrates a story from a time when both her children were students of Julien Day School. “When Shashwati was in Class IV, the school organised a dance programme for Rabindra Jayanti. While she was rejected, her two best friends were chosen. She was so heartbroken that she kept saying, ‘Naach shikhbo, naach shikhbo!’ (I want to learn how to dance!) Seeing her resolve, I took her to the Odissi dancer Sutapa Talukdar, and that’s where her journey began.” Shashwati is quick to add, “Studying dance in this family was a lot like ‘Daktarer barite ekta engineer beriyechhe!’ (An engineer has been born to doctors!)”

Shashwati set up her own dance studio, Avni, in her parents’ courtyard, and has over 70 students today. 'I wanted to take classical dance away from the auditorium, and back to an intimate setting,' she says

For Shashwati, pursuing the arts seemed easy. Her parents were never the sort to pressure her academically. “They would say, ‘Boards achhe to ki hoyechhe? (So what if your boards are coming up?) Carry on with whatever you are doing. Even if you study for two hours, that is fine with us.’ Our grades never mattered all that much.” Minakshi adds that she had tried to instil in her children an artist’s ethos: “The very idea of recreation was to create art.”

Even though Minakshi left Julien Day School in 1981, the teaching bug never quite left her. Once the studio was set up in Brahmapur, she founded her very own Minakshi Garai Art Circle on the first floor, teaching art to everyone from five-year-olds to amateur artists. The studio itself was Tarak’s idea, a dream that finally became reality in 1992. He says, “Most artists are restricted in terms of space. They can’t make a huge studio. Even commercial artists can only hope that after their passing, the next generation will use their home. I was not plagued by these worries. While building this space, I wanted the freedom to do any work.”

When it came to his kids, Tarak always had an inkling that they would follow in his footsteps. “Even though we never forced them, I expected the kids to be artists,” says Tarak. Indranil then adds, “One thing everyone should learn from Tarak Garai is his dedication to his work. He has worked every day of his life, and sculpting for him is like breathing.”

Tarak stopped selling his sculptures 25 years ago and now archives over 300 of his works at Garai Art Centre. He wants to eventually consolidate his work at the National Gallery of Modern Art

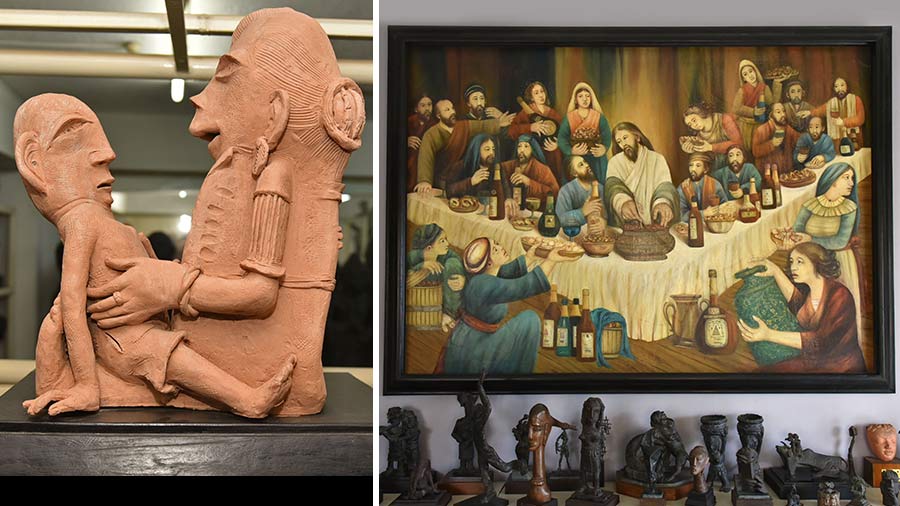

Tarak’s artistic style is even reflected in his parenting. He tells My Kolkata, “Growing up in my village, I lived in close proximity to Santhal tribals. I was particularly fascinated by how the mothers brought up their kids. While the men would not pay attention to the children, the women would take them to the farms, where they would breastfeed them while working.” Tarak says that after he moved to Kolkata, he saw how kids with wealthy parents were mostly brought up by domestic help. “I decided I wanted to highlight the importance of a mother’s love. Through my art, I want to depict a mother’s attention and affection.”

Many of Tarak’s sculptures have been influenced by the mother-child relationship. Though he specialises in bronze, he also finds ways of moulding his ideas into terracotta, stone, fibreglass and wood. Minakshi talks about how tribal mothers have influenced Tarak at a yet more elemental level. “His work often shows a mother at work, while her child climbs and plays around her. This was the same with him and the kids. They would climb all over him while he worked. He’d never mind that. He kept working.” Tarak’s fascination for mothers and maternity is evident in his painting, too. “Here I explore mythological themes like Sita with Luv and Kush,” he says. Shashwati adds that women reign supreme in her father’s work. “Baba always wants to explore female characters in his work. Even if he is making a portrait, it’s not about the features he draws; it’s about the character and personality he brings out.”

Though Indranil is a sculptor like his father, his genre is very different. He largely works in architectural sculpting across 12 mediums. Indranil met his wife, Payal, at Kala Bhavana. She is a potter and the two now run a company together. “Baba makes sculptures in his studio and is driven by personal satisfaction,” says Indranil. “I make large-scale sculptures which are meant for public spaces. While our philosophies are completely different, he has influenced me a great deal. In fact, my work was very similar to his until college, but then my travels started giving my style a very different direction.” Shashwati is impressed by her brother’s melding of business and art: “All his life, he saw Baba creating art but not getting into its business angle. Selling art is an art in itself. My brother mastered this brilliantly.”

Every corner of the house has art created by Tarak and Minakshi

To be young at art

For Minakshi, the central focus of all her paintings is the human figure. The people around her are her inspirations. Long ago, Minakshi says she lost a friend to depression. This only heightened her empathy. She says, “So many housewives feel the same way because they don’t have anything to do, especially after their children grow up. So, I began teaching a class that would help women create art from waste materials. Not only did I want to keep them engaged and bring them joy, I also wanted to give them a chance to find their own occupation. I feel all women must have financial independence, irrespective of what they do.”

During the pandemic, Minakshi took both her art and her teaching online. She started virtual classes and dabbled in digital art, too: “For years, I saw my husband paint, but I held myself back. Teaching also became my priority from a young age, but a few years ago, my son gifted me a tablet and my grandson taught me how to draw on it. There was no turning back.” Despite the several benefits of technology, however, Minakshi says the lived environment of the Garai Art Centre cannot be matched. “Normally, children are between the four walls of their school, but the atmosphere here is completely different. Be it art or dance, there is a constant sharing of ideas, and students think of us as their ‘kaku’ and ‘kaki’.”

For the Garais, art is embedded in the very soul of the family

In her Odissi life, Shashwati likes to explore abstract themes. “My work has influences from mythology, but it also engages with things like sound, space and movement. A knee injury made me realise that while classical dance is very soulful, it lacks fitness. I have been working with my guru, Sharmila Biswas, for the past 15 years to bring fitness into our form and style.” Championing her efforts, Tarak says, “Some dancers stick to the paths shown by their guru, but Shashwati wanted to create something new and take it across the globe.”

In a house of such diverse creative voices, differences are inevitable. Shashwati says, “We four have constant clashes, but you can’t grow without them either. My brother and father go in opposite directions on most things, but they also meet somewhere because they need each other.” Indranil clarifies that his differences with his father are mostly linked to the materials they use. “There are a lot of materials that I use which do not have the permanency of bronze. Baba feels that a sculpture should be permanent while I think it can have a shelf life.” Minakshi adds, “Though dancing, painting and sculpting are very different, we never create distinctions between art forms. The similarity in our creative voice is what keeps us close.”

Tarak says he works for over 10 hours every day: “We are all workaholics in this house.” His daughter says her parents’ ethic of constant work sometimes leaves her concerned. “At times, I want them to take it easy and go on vacations like other parents, but I also think it is wonderful that they are so active.” To this, Tarak adds, “I believe that if you concentrate on work and don't get distracted, you will never get old.” It is Minakshi, though, who must be given the last word. She says, “Our families used to believe that ‘artist hole khete pabena’ (‘artists will never be able to earn enough to eat), but we have proved everyone wrong. This only shows that if one is strong in her or his field, any artist can not only survive, but thrive.”