Art and culture have a unique relationship. But what happens when two artists from different cultures meet, fall in love and get married?

Bendangnungsang and Sandy Ao come from very two different worlds — Nagaland and China — who met in Kolkata and now call it their home. What brought them together is their artistic sensibility. Fifty years on, when My Kolkata sat down for a chat with the couple, their shared love of all things art was eminent and keeping everyone company was a plate of Bengali pithe.

Finding art

Bendangnungsang, the first Naga student of the Government College of Art and Craft, Kolkata, showed a flair for art first at age 10, when he started making sketches of King George V’s image on Rs 1 coins.“I began my artistic journey by only drawing the outline, and slowly made my way to more details,” said Bendangnungsang, who was born in Kohima, Nagaland, and grew up in a nearby town.

No one in Bendangnungsang’s family had an artistic bent but his love for sketching prompted his father to send him colouring books from Shillong. In school, his skills started getting attention with caricatures of teachers and friends. “We would draw them exactly in the position they were in, which was often hilarious. Soon, they asked us to draw for the exhibitions and fairs in school,” he laughed.

After school, Bendangnungsang’s family insisted that he pursue engineering and he got admitted into the electric engineering course at IIT Kharagpur, only to realise it wasn’t his calling. “I soon knew that it wasn’t for me and left the course within four months. During the gap year, I thought of doing a BA degree but a book about artistic work by Italian author Alberto Moravia inspired me and I knew that was my life.”

Bendangnungsang’s brother-in-law got his family to agree to this rather unusual choice of subject. He met an artist from Bengal who was working in the Art and Culture Department of Nagaland. “He gave me some lessons in sketching and watercolour, and prepared me for my application to the Government College of Art and Craft. I passed the entrance exam and became the first Naga student of the college.”

Bendangnungsang with his oil painting titled, ‘Naga War Dancers’ depicting a battalion from the state

Sandy continues to be the only person of Chinese origin to have studied at the college. Her early tryst with art was unusual, too, having grown up in the Chinese community in Kolkata where most were involved in the leather business or owned restaurants.

“Most of the Chinese population in Kolkata works in the shoe or leather industry and lives within the community. My family was also from a shoe-making background and expected me to follow in their footsteps, even enrolling me into a Chinese school,” Sandy said, reminiscing about her clogged existence in her family’s Bentinck Street home. “I could not even see the sky from that house. I would run away to my grandmother’s place in Tangra during summers just to see the beautiful sunsets. At that time, I felt a deep desire to paint them. In the city, you want to find your special place. For me, it was nature.”

Sandy found peace in art but she became serious about it much later. “I was born with a hole in my heart. As an adolescent, the problem aggravated and I spent all my time in bed, suffering in agony. I just had one thought; I may not live for long, but I must do something I like.”

The push came from a deaf-mute girl in her neighbourhood who did batik art. “She told me about the Government College of Art and Craft. When I went for the entrance test, my Chinese education caught up with me. I couldn’t understand the terms mentioned in the exam paper, including something as fundamental as the word ‘composition’.” A professor noticed Sandy’s confusion and asked her to return with colours. Since she couldn’t go back home, she borrowed some from a friend on Park Street and rushed back. “The professor asked me to draw a landscape painting of anything from my imagination. After a few days, I saw my name on the list of 100 selected candidates from over 1,000 applicants.”

Sandy’s love for nature is evident in these watercolour paintings of (top left) autumn, (bottom left) sunflowers and (right) bamboo. The latter even employed Batik on paper

But the battle was far from over. The interview required Sandy to appear with her parents but they were not comfortable with her studying something they were not familiar with. “I told the college that my parents couldn’t come because of the language problem (laughs)! Verifying the documents was also a task, because they wouldn’t accept my Class X certificate as it was written in Chinese. My parents were more concerned about what would happen to my health if I spent long hours away from home. The problems peaked when the authorities asked me to get a character certificate, and my reaction was, ‘I don’t even understand what the doctor says about my health, how do I understand what a character certificate is?’ I finally confronted the authorities, telling them that despite passing the competitive screening, these challenges were created because of my colour and ethnicity. I called out racism in 1969, and finally got admitted.”

A love story called art

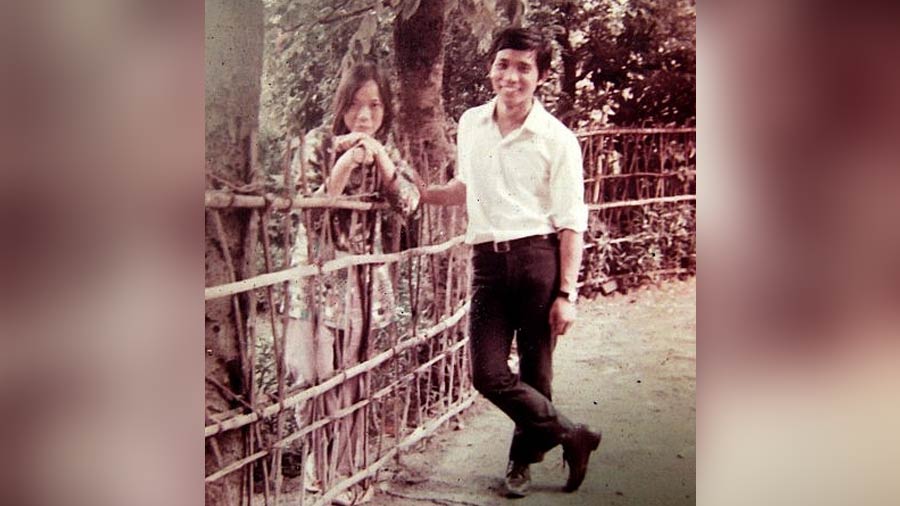

Sandy and Bendangnungsang during their college days

One day, Sandy was with her classmates, having just received the results of an exam. Like many of her peers in first year, she too would see the work of her college seniors to understand how they painted. That day, she walked up to a certain third-year student from Nagaland.

“I saw his painting and asked both him and myself, ‘What am I doing here? I can never paint like this!’ He assured me that I would also come up with similar stuff by the time I reached third year,” Sandy recalled. That is where her story intersected with Bendangnungsang. “He was very quiet and I hung onto him for guidance. Whenever we went sketching, I made sure no Chinese people saw us, because if they did, they would tell my mom, ‘Mrs Wong, your daughter is sitting with some boys on the roadside!’ she laughed.

Sandy created these handmade paper fans with watercolour

Their ethnicity wasn’t the only roadblock though. “As a 14-year-old, my doctor once told me after a check-up that I shouldn’t get married because my heart problem would cause major complications in child-bearing. I laughed it off then, but in college I clearly told him that I wasn’t the marrying kind. He would always tell me that it was fine and he didn’t care!”

In 1974, Sandy travelled to Nagaland to meet Bendangnungsang’s family. When she told her own family about the match, there was a lot of resistance. “My parents were quite known in Kolkata’s Chinese society, and they were not comfortable with me marrying someone from a different culture. Everyday, they would read about Nagaland in Chinese-translated newspapers and ask me why I wanted to go there! (chuckles) But I was very confident about marrying him, not having children, and painting for the rest of my life.”

The two finally married in 1975 and a few years later became parents to a son — Allan Temjen Ao, doting son and now guitarist for Bangla rock band Fossils.

Lessons in art and beyond

When Sandy joined the art college, her Chinese school principal asked if she could teach the students. “I argued that I hadn’t learnt anything yet, but he insisted that I teach the children whatever I would learn and said that he would give me Rs 20 as salary. When my siblings found out, they joked that even the house cleaner earned more, but I was okay with it, since my college fee was Rs 4 and it let me pay for my own education,” she said, adding that she took a leave from college every Thursday and taught three classes.

This didn’t make her supplies any cheaper and Sandy couldn’t afford to waste any paper in college. “In a lane near Metro cinema, this old gentleman ran Sen & Co. in his garage. He would sell expired paper for as cheap as 20 paise. I developed a great friendship with him during our visits, and it was a great hub for artists!”

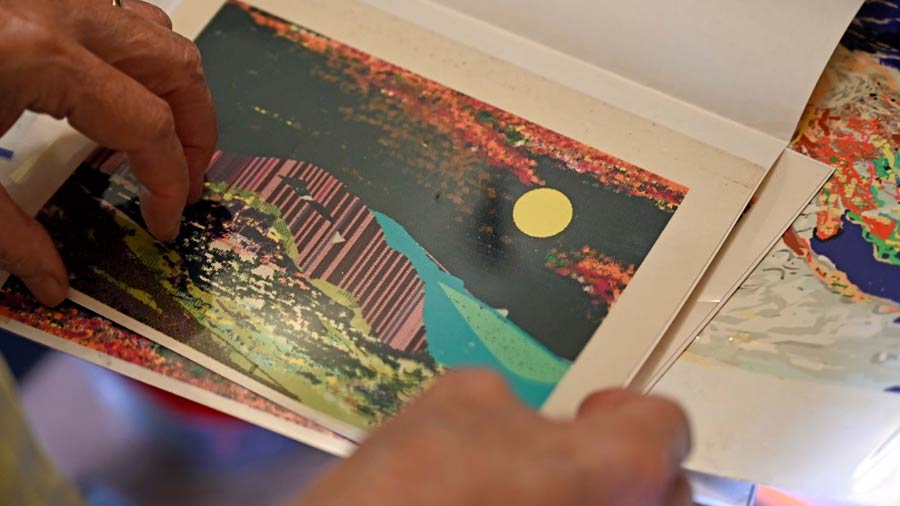

When computers came, Sandy made a series of digital paintings on Coral Draw

With time, their art evolved. Bendangnungsang remembered seeing a diorama painting at the Indian Museum and realised that was the benchmark he wanted to set for his art. “I thought that if I could paint like that, it would be enough for me. Initially, I painted whatever I could imagine, and combined it with what I learnt at college. Later, I thought of blending our Naga art with contemporary styles, just to see what would come out. To this day, I still create with this drive.” Sandy added, “Every Bengali child can sing, draw, dance and write because there is a push. Nagas are very good with their hands, be it in craft, music or painting, but they aren’t aware of their inherent skill. In our case, all our friends and neighbours want us to be nothing beyond our Chinese identity. In college, I was taught many western styles but the moment I graduated, I felt like I was gravitating towards a Chinese style. For Chinese people, my work wasn’t Chinese enough, while people outside the community found it to be heavy in Chinese influence. While his art came from a thorough understanding of the Naga culture, I was a narcissist who wanted to prove something to the world!”

Into the outside world

After graduation, Bendangnungsang spent some time looking for work, despite being eligible for a national scholarship in his post-graduation. “Since he graduated in First Class, he was one of the only two candidates from the college who were eligible. But, his father retired just before he had to go to Delhi for an interview, and his sister pointed out he had a good education but his younger brothers were still studying. This made him decide to shoulder their responsibility, and he gave up the chance,” said Sandy.

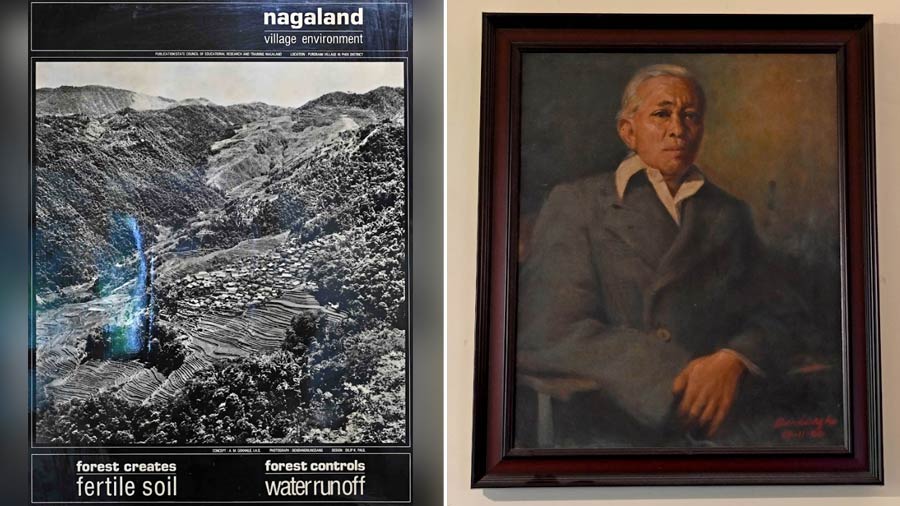

A new chance came in November 1972, when the Nagaland government sent word about a vacancy in the agriculture department. “That month marked the 100th anniversary of American missionary Edward Winter Clark’s arrival in Nagaland. The department wanted help with the celebrations and my artistic background led them to contact me. The authorities even said that we could discuss a prospective job after the assignment was completed.” After working for the event, Bendangnungsang was selected.

The process, however, wasn’t as straightforward as expected. “They didn’t have a post for him at first, but the agriculture department valued him. So, they created an artist-cum-photographer’s post for him. He didn’t even know how to use a camera, but his friend taught him how to operate one before the job. He went on to take the picture which brought the Nagaland government a decade-long grant from the Canada government,” she said.

The photograph Bendangnungsang took of Purobami village in Nagaland, which earned the Canada government’s grant and (right) the oil painting he made of his father, Anang Ao

Soon, Bendangnungsang grew an affinity to photography. “I didn’t have much time to do creative work, but photography became a hobby so time passed by really fast.”

As an artist, he drew a variety of illustrations and signs to communicate with villagers. “It wasn’t exactly creative work and when I saw his artistic side waning, I encouraged him to carry on painting. His renewed vigour led him to paint many Speaker portraits in the Nagaland Assembly, and his work made his way to the Nagaland Raj Bhavan and earned him the Governor’s Medal!” Sandy recalled.

Sandy’s life took a different trajectory. Having become a mother, she found herself occupied with domestic and childcare duties. “When Allan was four, he saw me painting and said ‘No, this is Papa’s work.’(chuckles) Then again, our society is still very chauvinistic. This is why I urge female artists to always sell their paintings at a good price. Only when you make money from your art will your husband value your art, and encourage you to paint over housework.”

She also pointed out how nuanced the implications of her gender were in her art. “I started painting with watercolours in college and all my work was done in one stroke. When Allan was in school, the computer was introduced and I started dabbling in digital art, too. But I always avoided oil painting because that was my husband’s domain and I didn’t want to get influenced by him, but do something original.”

Another reason Sandy kept away from oils is the time it requires. “Painting on oil needs full concentration and takes up the whole day. You can’t just leave the painting to cook or clean. If I insisted on doing oil painting, who would bring up our child or run the house? It was not possible to have two dreamers in the house.”

Allan with Sandy and Bendangnungsang

But life came full circle, when the same Allan encouraged her to paint again. “He had started college by then, so after a gap of 20 years, I went back to art and picked up exactly where I had left things. This is what I keep telling people, your artistic side never dies.”

Her experience came from how she found herself gravitating back towards nature, the same thing that drew her to art as a bedridden child. “I don’t understand someone else’s culture very well, so I feel like I might get something wrong if I use it in my art. My paintings only come from things that I know or have experienced. In the end, nature always gives me peace, but never questions me.”

Bendangnungsang’s smile grew wider when Sandy expressed joy at getting back to art. “She has distinct soul-searching paintings which stand out with her vision.”

Blushing, Sandy comes up with her own compliment. “He comes up with these beautiful concepts. Even now I see his paintings and think, ‘How does he imagine all this?’”

But beyond the philosophical concepts, art continues to retain a childlike wonder for both. For him, it is exercising the occasional muscle in the midst of commissioned work. “Even while doing a professional project, I break away and paint landscapes for myself.” For her, it is a reminder of the vow she made to herself. “I have lived the three-year ultimatum I gave to myself multiple times. Art has made my life full.”