My phone beeped as we waited by the roadside, the seemingly endless military convoy rolling past our car. It was a message from a friend: “Where are you?”

“Kupwara,” I replied.

“Oh my god! THAT Kupwara?” she messaged back.

“Yes, and headed for the PoK border,” I replied.

“WHAT? After all we have read and heard, be careful,” she wrote back.

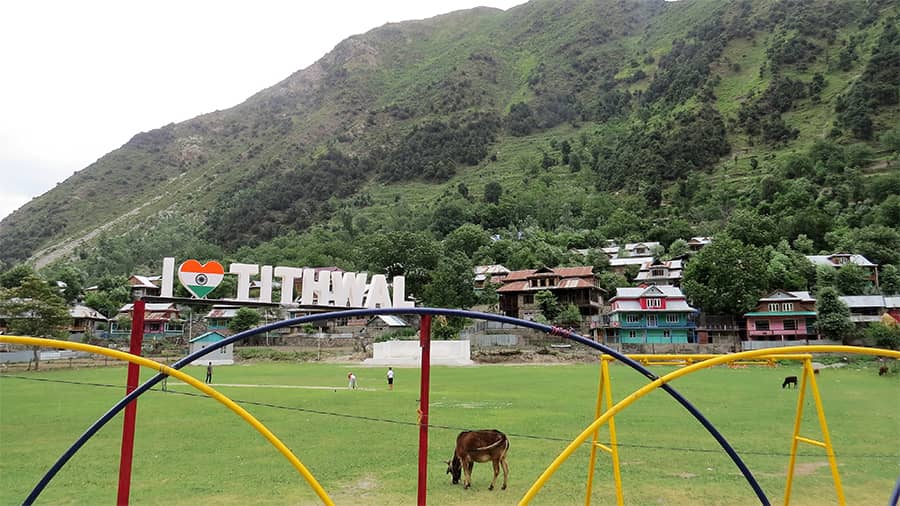

And careful we had to be, about several things. Our destination was the border town of Tangdhar in the extreme west of Kashmir’s Kupwara district, and onward to Tithwal, touted as the last village in India on the PoK border. Several drivers had refused to do this trip, until we had found Tanveer. He had driven for the military and, so, had fewer fears of the uniform.

Those fears, or rather, the willingness to avoid the uniform, were not unfounded, we had discovered. For instance, when we had left Gurez, there had been a check on the Razdan Pass. A soldier, barely in his 20s, had asked in the sternest of tones, bordering on rude: “Are you taking something from there?”

“Yes, food,” I replied, wondering what all could qualify as “something”.

“Should we check the car?” he snapped again.

“You are free to do so,” I said.

“Never mind, I’ll take your word for it,” his voice had softened. He had gone on to add: “We are stuck here. What do you people come here for?”

I had not known what to say. We had been hearing it repeatedly from the soldiers we had met on the way.

On the way to Tangdhar Urmi Mukherjee

“Jalebi lete jana”

To go to Tangdhar in Karnah, we had to take a permit from Kupwara police. We had just set off after collecting it when security men stopped us to let the convoy pass. Truck after truck rolled past, a soldier in position with an assault weapon atop each one. We could leave only after about 10 minutes.

The first checkpoint was at Chowkibal, where the jawan on duty was from Bengal. He chatted with us merrily before letting us pass. But just as we were about to drive off, he came running. “Kaku, kaku, show me your IDs,” he panted. He was addressing my companion as kaku (uncle)! He had been so busy chatting with people from his homeland that he had forgotten all about the identity check.

The next round of checks came only a few paces ahead, and then again, on the Sadhna Pass about 30 minutes later. The 10,269ft pass was terribly windy and chilly, and we were neither allowed to get off nor take pictures. Only our male companion was asked to go and enter the details.

“Jalebi lete jana (take the jalebis),” a soldier told him. Jalebis! Where? “You’ll find them right next to the entry counter,” he said.

Our overnight stay in Tangdhar had been decided only at Chandigam. The manager at the JKTDC guest house had helped us book our stay at Hotel Gareeb Nawaaz. However, when we reached there, it turned out that only one room had a bed, while the other had the sleeping arrangement on the floor. But three of us had medical issues that made sleeping on the floor undesirable.

“We’ll have to find another accommodation,” I said. But Farooq Lone, the owner, ruled it out. “You go to Tithwal. I will arrange a bed,” he assured us.

Tithwal Urmi Mukherjee

Anxious moments

It wasn’t difficult getting the permit for Tithwal from Tangdhar police station. But it also said “Seemar” on top and we had no idea about its significance. Anyhow, we set off giddy with happiness, because none of us had expected to get the permit to Tithwal so easily.

Our euphoria was short-lived, though. When we showed the permit at the first checkpoint, we were asked for a photocopy. And, we had none.

The officer on duty told us to go back and get it. But Tangdhar was a long way behind. Finally, I asked him, very gently, if we could get the photocopy done somewhere ahead and drop it on the way back. Reluctantly, he agreed. “Get it at Dringla,” he said, adding: “And remember, the guy at the next checkpoint won’t be so considerate.”

Unfortunately, we found out at Dringla that it had no power for two days. We drove on, getting nervous with every passing second about confronting the men at the second checkpoint. They were right outside Dringla. The officer was a young soldier — handsome, but with a cold, hard look in his eyes. To make matters worse, it turned out that Tanveer’s name was written incorrectly on the permit.

“That’s the end of it,” I thought grimly, keeping mum as the officer gave Tanveer hell for no fault of his. But in the past, I had been scolded — by Tanveer himself — for speaking up. “Let me handle them, madam. We are used to them; you are not,” he had said.

Finally, sensing a lull in the storm, I asked the officer very quietly whether we could get the permit photocopied in Tithwal. Glaring at Tanveer all the while, he said: “Get it done positively in Tithwal and drop it on your way back.” We heaved a sigh of relief and set off again.

The home screen of the author’s phone showing two time zones Urmi Mukherjee

The last post

Tithwal was only minutes away. We stopped at the first photocopier we could spot and got the job done. Then, we went on down the straight road, for what we did not know. At the final checkpoint, we were told that we could go “as far as the road went, till the last Indian post on the POK border”. So, that was Seemar!

The road carved into the mountainside, snaked parallel to the Kishanganga, which we had already met in Gurez. On the other side of the river, just metres away, with a road similarly carved into the mountainside, was PoK. The path ended at the mouth of Seemar and we could see the houses on both sides. My phone even showed two time zones — the “local time” half an hour behind India time .

Everything seemed calm; everything looked normal — until a soldier told us there were bunkers on the mountaintops on both sides and a few guns were possibly pointed at us from the other side right then. We chatted with him for some time, hearing the same refrain: “I am stuck here, waiting to go home in a few months.”

“Chai piyoge?”

On our way back to Tangdhar, we stopped before Dringla to hand over the photocopy. The officer was no longer in uniform but he came up to our car.

“So, what did you see there?” he asked, maintaining the sternness.

“We saw the border, the views,” I said, wondering if it was a test.

“You didn’t see the bridge?” he barked, referring to the one across the Kishanganga at Tithwal.

“Yes, it was closed,” I said. “Arre, you could have gone halfway up that bridge. It’s allowed,” he looked angry.

“Nobody told us,” I protested feebly and he said no more.

The next question came quite unexpectedly: “Chai piyoge? (Do you want tea?)”

“Yes, why not!” I replied, secretly relieved, and he jogged off to their camp to get it. When he returned, a jawan carried the tray behind him as he hopped down the stairs of the camp, like a child, much to our amusement. Suddenly, he was no longer a cold-eyed soldier but only a young man, possibly tired of “being stuck” away from home and temporarily excited by a rare encounter with outsiders.

On the way to Sadhna Pass Urmi Mukherjee

King-sized hospitality

At the next checkpoint, too, the officer had a chat with us, even managing a few jokes this time. But the biggest surprise came at Gareeb Nawaaz. Lone had conjured up a king-sized bed in those two hours, complete with a mattress and sheets!

We left for Srinagar the next morning. After a baggage scan and a detailed security check on the Sadhna Pass, we were finally free to go. “I hope there are no more tokens and security checks,” I said wearily. “Tokens and checks are what we have been getting for ages,” Tanveer’s voice was grim.

It suddenly dawned on me that he and the soldiers had perfectly summed up the situation in Kashmir in those few words. One party was endlessly “stuck” in an alien land, the natural beauty meaningless to them. The other was tired of the endless checks and the occasional bullying. And visitors like us can only silently watch them play pawns in the geopolitical drama called Kashmir.