I had just trained my lens on a cinereous tit when I caught a movement out of the corner of my eye. I turned to catch a young woman waving from her yard beyond the little walnut grove where I was looking for birds. It was clearly an invitation to go in.

I crossed the rows of walnut trees and entered the fenced-off yard. The smiling woman was sitting on a sheet spread out on the grass, a pile of leafy branches next to her. She was pulling out the leaves and chopping them up with a machete.

After answering her questions — who I was, where I had come from, who was with me — I asked her what she was doing. “These are mulberry leaves to feed the silkworms we rear,” she replied.

I could not believe my ears! Only a day ago, I had been asking around to find a family that reared silkworms, without any success. And now, I had bumped into one, just like that!

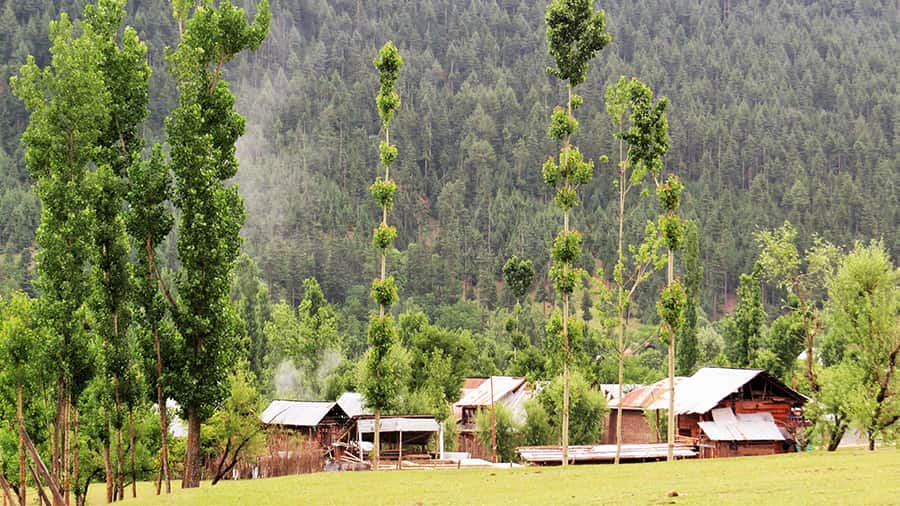

Chandigam village in Lolab

The silk route

We were at Chandigam village in the Lolab valley of Kashmir’s Kupwara district. Watered by the Lalkul stream, Lolab is marked by its vast paddy fields, hemmed in by low hills forested by deodars. And, it is also a hub of sericulture, about which we had got to know only the previous afternoon.

The road to Bangus Valley

We had left the government guest house — the only tourist accommodation in Chandigam — for a post-lunch stroll. A local man had willingly given us a tour of the village, saying a lot of it had been “rebuilt after militants destroyed everything”. He had also shown us the wild mulberries, locally called “tul”, and told us about sericulture.

“In the old days, there would be a fair in this village. People would come from afar to buy the silkworm cocoons. But now, villagers have to go to Srinagar to sell them,” he said. “Can you take me to a family that still practises sericulture?” I had asked. But he did not know any.

Dreams and reality

As I spoke to the young woman, Suraiya, we were joined by her younger cousin, Tabassum. I asked them if I could see the silkworms and they readily agreed. They took me upstairs and opened a locked door. It was dark inside and Tabassum switched on a dim light. It shone on rows of wooden shelves on the walls, each with a bed of shredded mulberry leaves, on which the worms were feasting.

Suraiya (centre) shreds mulberry leaves as Tabassum captures the writer on her phone. The boy is Tabassum's brother

We later learned at the nearby sericulture assistant’s office that Tabassum’s is among 20 families in Chandigam that rear silkworms. The department gets the “seed” (larvae) from Bangalore and distributes it among the families. They feed the worms, monitored by the sericulture assistant, until the cocoons form. Last year, Tabassum’s family earned around Rs 75,000 from the business.

Tabassum brews a cup of noon chai for the writer

After showing me the silkworms, Tabassum took me to the adjoining kitchen and brewed a cup of noon chai for me. As I drank the tea and munched on the bakarkhani she had served it with, she told me about her dreams of becoming a doctor. She said she was studying medicine.

Down at the yard later, I met her father Md Shafi Bhat. “Take my daughter with you to the city,” he said. “What about her medical course?” I asked. “What medical course?” he looked surprised.

It turned out that Tabassum was a Plus-Two science student at the local school. “How can we afford a medical course for her?” Bhat laughed. Suraiya was already engaged to someone in Kupwara. It would be Tabassum’s turn next. I could not bear to look at the girl.

Lolab Valley is marked by its paddy fields

Around Lolab Valley

It was time to bid the family goodbye because we planned to take a trip around the Lolab Valley that morning. Our first stop was Satbaran, a stone structure with seven doors built on a hilltop in Kalaroos village, 20km to the north-west of Chandigam.

The village gets its name from a network of natural underground caves and tunnels rumoured to lead to Russia. Hence the name, ‘Qila-e-Roos’ or the ‘Fort of Russia’, which has over the years been diluted to ‘Kalaroos’. There is no truth to those rumours, though.

Satbaran at Kalaroos village, Lolab Valley

It was a steep climb to Satbaran and the caves were a hike of another kilometre through the hills. So, we gave the latter a skip. Our next stop was at Devar village in another part of Lolab. A section of it is being developed as a park to attract tourists. Yellow-billed blue magpies had a free run of the sprawling grounds and Bakarwal herdsmen grazed their sheep on the far side.

TP, the gateway to Bangus Valley. Here stands a signboard that says 'Welcome to Bangus Valley'. It is a junction from where one road branches off towards Bangus Valley

A nightmarish hike

The next morning, we left for another attraction in Kupwara, Bangus valley, south-west of Lolab. We knew that we would have to hike about a kilometre-long unmotorable stretch. But nothing had prepared us for the nightmare that was about to unfold.

Our approach to the valley up a beautiful deodar-lined road was halted by what looked like a freshly ploughed field. And it extended as far as we could see. This was the stretch that needed to be hiked! Apparently, the government intended to make it motorable. Accordingly, the track had been dug up. But before it could be tarred, came the rains, turning it into a kilometre-long stretch of slush.

“It’s just a 15-minute walk,” one of the men who hung around the place assured us. Fifteen minutes later, we were bang in the middle of that godforsaken track, our feet sinking up to the ankles in the muck with every step and our shoes no longer distinguishable from the surrounding slush.

Purple irises and cushion spurges in Bangus Valley

I was the only one to reach the end of the road, my three companions having turned back somewhere along the way. And stretching before me in all its glory was a gorgeous vale traversed by a swift stream, cushion spurges and purple irises adding more colour to the grassy meadows.

I followed the stream as the hills rose like columns of a cathedral on both sides. The meadows seemed to stretch as far as my eyes could go, with the river meandering through the seemingly endless verdant hills. Finally, I climbed a hill on the right and caught a glimpse of some Gujjar huts. Horses and buffaloes grazed close by.

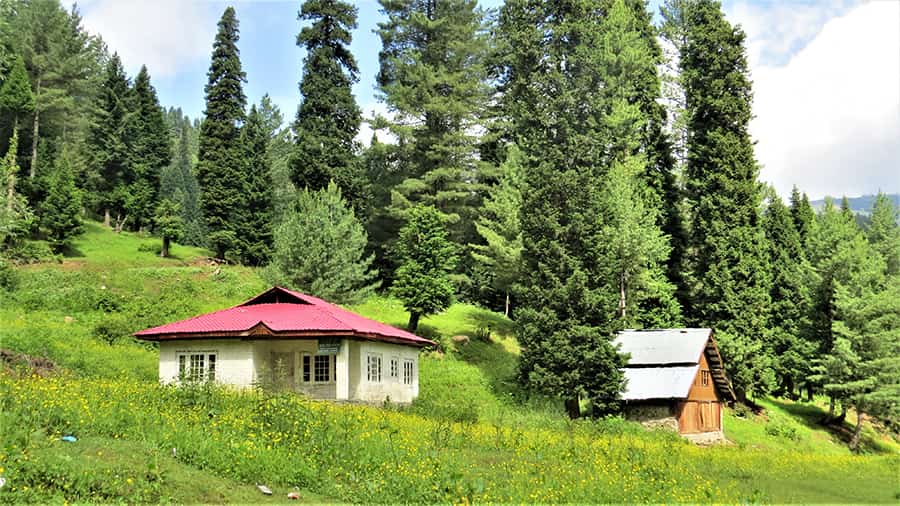

Gujjar huts in Bangus Valley

On the mud track, I had seen a woman on horseback going in the opposite direction. And now, I got the idea of borrowing a horse from the Gujjars to return to the car. I approached the nearest hut and found the family of five — an elderly couple, a younger couple and a boy — lazing outside. They greeted me warmly.

The Gujjar family that invited me in and arranged my horse. The man on the right is Md Shafi

Kind-hearted strangers

To my dismay, though, they turned down my request, saying even horses could not negotiate that road. Instead, they invited me to sit in their hut, get warm by the kitchen fire and have a cup of tea. But once I settled down snugly and we started talking, the younger man, Md Shafi, changed his mind.

“She is from the plains. They are not used to such terrain. We must help her,” he told his parents and wife. They nodded in agreement, raising my hopes. Shafi went out for a while and returned to let me know that the horse was being readied.

“Why don’t you have lunch with us,” he suggested and the others voiced their approval. I had to refuse, though, saying my companions would be waiting in the car. “You could have spent the night here with us,” said Shafi. But I had to go. The sky was getting dark and we could hear the low rumble of thunderclouds.

The horse arrived in about 15 minutes and Shafi helped me mount it. He also instructed the young chap leading the horse to go slow so that I wouldn’t take a tumble. The family saw me off as I headed out, sitting stiffly on the horse. Slowly, as my body adjusted to the rhythmic movements of the animal, I loosened up. And that’s when I became aware of the ethereal beauty all around.

The horse trotted up and down the undulating terrain, crossing rivulets hurtling down from the hilltop to feed the bigger stream below. The entire landscape was carpeted in green, dotted with the yellows, whites and purples of wildflowers. Not a soul was in sight and, in that very moment, I felt one with that magnificent valley.

I left Bangus with that image etched in my memory forever.