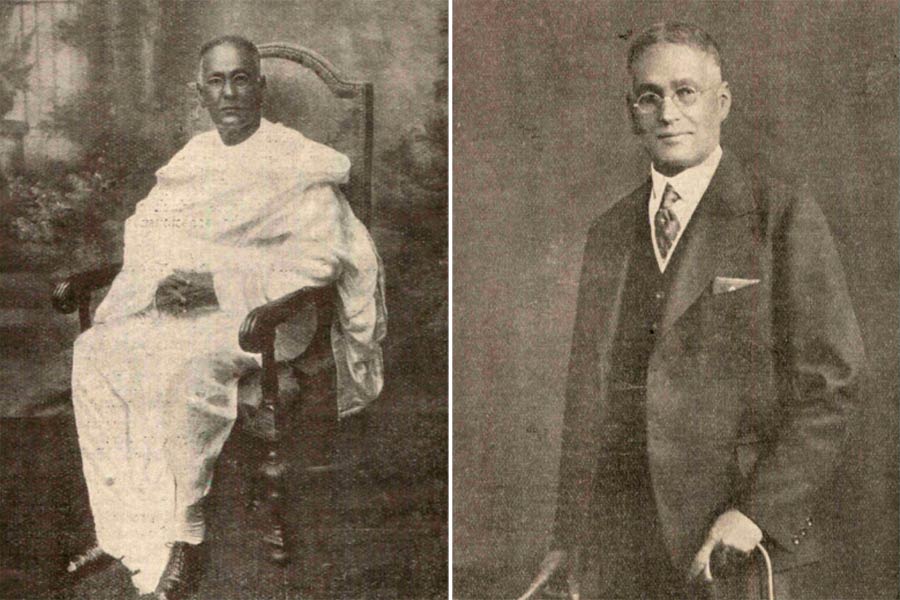

Inside Kolkata’s Victoria Memorial, the only statue of an Indian — tucked away towards the gate across St Paul’s Cathedral — is that of Sir RN Mookerjee.

He was a Renaissance man never acknowledged as one. Just a Calcutta street to his name scarcely does him justice. The man co-founded the iron works of The Indian Iron and Steel Company (IISCO) at Burnpur, Asansol; built Garden Reach Ship Builders and the Hooghly docks. He constructed the Palta water works, Victoria Memorial and Howrah Bridge. He co-founded the Indian Statistical Institute, mentored water supply projects in Lucknow, Allahabad, Agra, and Kanpur. He founded Martin & Co. After his partner passed away, he acquired Burn Company and renamed it Martin and Burn Company with no personal mention anywhere. He created Martin Rail around affordable lightweight narrow gauge trains linking Bihar, Delhi, and Bengal, constructed Hooghly Dockyard and the State Assembly. If one drives around Calcutta, Sir RNM is everywhere, and yet ironically nowhere.

Sir R N Mookerjee is the only Indian whoSE statue stands inside Victoria Memorial Wikimedia Commons

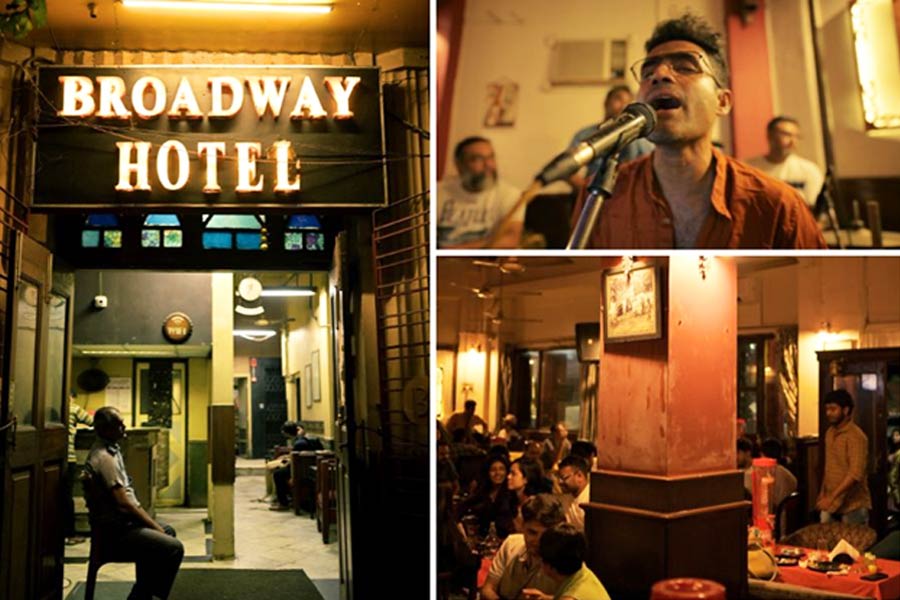

The Camac Street mansion that Sir RNM lived in was one of the grandest of its times. 1910 vintage, stately, teak-panelled, with glittering chandeliers, the best of wines, the viceroy for an evening guest, ballroom dancing, sentries at gates. He could have been English but for his skin colour.

When the family fortunes began to fail in the generation after him, the attention to the mansion began declining. The irony is that while his architectural creations survived, his home almost didn’t… until about 18 years ago when Aditya Poddar returned from Singapore to follow a lead that said ‘Sir RNM’s house is up for sale.’

The restoration of the mansion began in 2011 and ended in 2016

The well-travelled Poddar did not miss the uniqueness of the opportunity. Even if he were to overlook the Sir RNM angle, there was still the prospect of doing what would be celebrated the world over — restore and reuse. He could do what he had admired in others — the Raffles Hotel in Singapore, a Warsaw heritage mansion that was deconstructed and reconstructed around the same design when the owner could have deviated, cafes and stores housed inside structures 150 years old.

When the Sir RNM whisper floated by, Poddar said, ‘My time to do the same in Calcutta.’ This must have been a courageous decision. Over the years, the value of the property has appreciated and corresponding to this the rent has risen as well, but then so have the costs of people, consumables and maintenance. He does not scribble numbers in my presence, but I can assume that had this generated an annual return on employed capital anywhere in the high double-digit percentages, he would have brought into another heritage property. He doesn’t say, ‘wealth destroyer’ but I can pick the feelers because he said, ‘Normal mein parta baithega nahi’. For this itself, Poddar should be feted and felicitated. He has done Kolkata’s heritage an ehsaan. He could have let the property go and shrugged his shoulders. He waded in instead.

‘When I first walked into this mansion that had not been maintained since 1970, I could feel the aura of the man who had built it,’ says Aditya Poddar, who spent five years repairing and restoring the home

But I would rather let Poddar narrate his hard speak (interspersed every few minutes with ‘Don’t write this line!’).

“When I first walked into this mansion that had not been maintained since 1970, I could feel the aura of the man who had built it. I closed my eyes; I could ‘see’ the Chancellor and the Viceroy at the long table, Tagore walking in the garden and Motilal Nehru near the window. I walked over to check the wood; it was La Salle. There is a line by the man who thrust a candle inside to look for the first time at the discovered tomb of Tutankhamen: ‘Everywhere the glint of gold.’ Inside the house of Sir ‘RN’, there was ‘everywhere the hint of class’. I was living in Singapore then; I decided instinctively: ‘Theek karte hain is ko.’

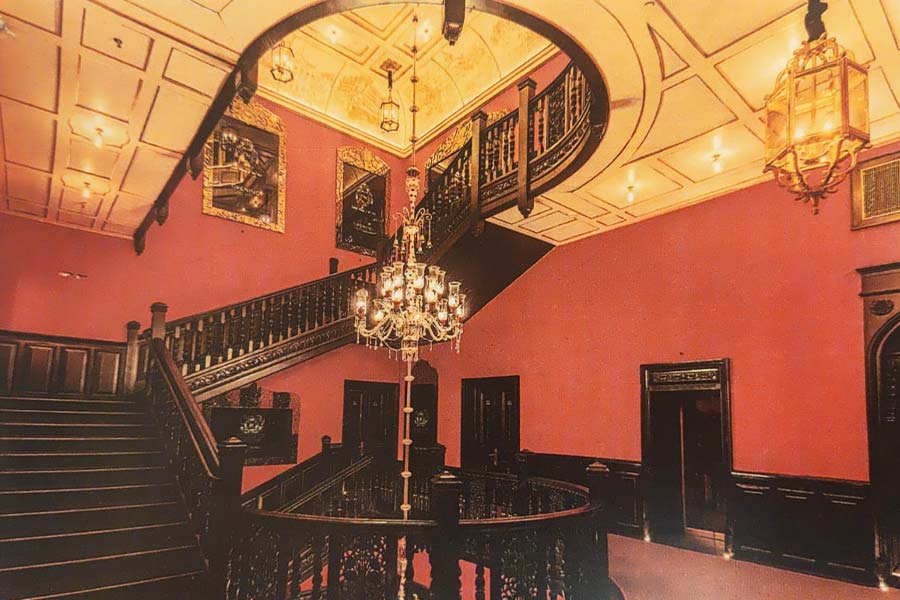

A portion of the restored mansion

“I resettled. Just as well. This Camac Street property warranted my sustained presence. There were 22 people who had occupied the property and needed to be removed, and just like everywhere else, 21 agreed and the last one refused. There were istriwallahs, rickshawallahs and thelawallahs who had to be evacuated. The last generation of those who had lived there had walked away with the windows and doors (‘Poochhiye mat!’). There were permissions to be sought for everything. One went back a few weeks later to the same municipal desk and discovered that the one who was just about to issue a permission letter had been shifted. And finally, there was the biggest shocker: ‘But this is a heritage building and we can’t give you permission to change anything.’

“Three things got me through. One was that I was in a tunnel and couldn’t turn around, so everyday I would turn up at work. Perseverance did for me what luck couldn’t. Then there was Alapan Bandopadhyay — please write his name. He was the only one with some authority who assisted and facilitated. And lastly, the nasha. How does one explain that one keeps putting money into a property when even the most basic calculations do not indicate that you can ever cover your byaaj (interest)?

“The restoration started in 2011 and ended in 2016. I designed the place myself. I was my own architect. From the outset, there were some objectives: the property would be monetised to fund its maintenance; the property would need to have a wider relevance so that a large number of visitors could see its shaan-o-shaukat; it would have to be Instagrammable to initiate a virtuous youth footfall cycle so that more people came to shop, which in turn would have provided us with a handle to increase rents and then look after the property even better.

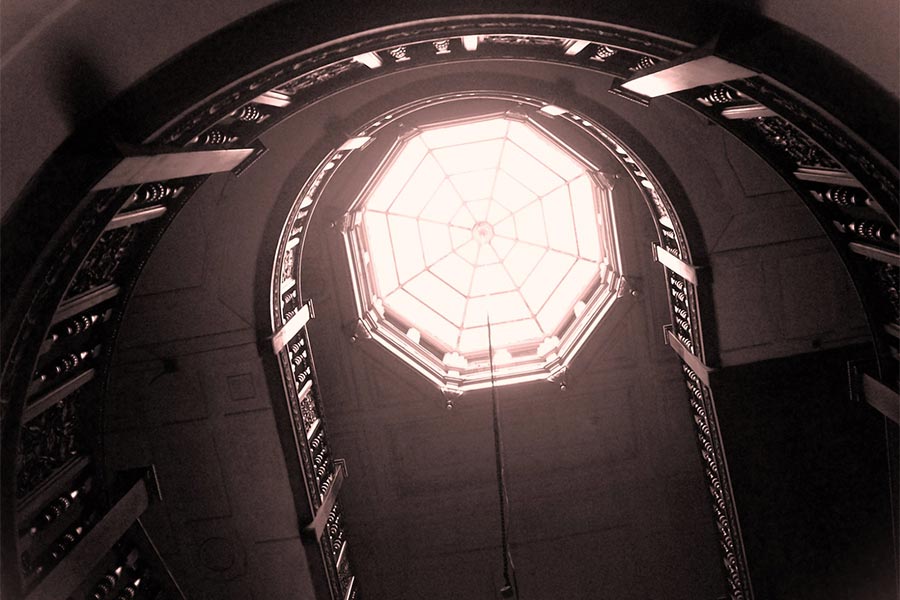

One of the highlights is the skylight, which is now functional again

“We patiently revitalised three chandelier layers. We brought the wooden staircase to its former glory. We got the skylight to function again. We put the stained glass back piece by piece. When we finished, we didn’t have only a happening place; we had curated possibly Calcutta’s best retail destination. When anyone walked in, the first thing that would transpire was a jaw drop. We created a spectacle.

“The restoration taught me more than the cost of materials; it taught me the cost of money stuck in a project like this. Every single delay increased the project cost; every single delay increased the cost of staying in business; every single delay discouraged well-meaning restorers from attempting the same; every single delay set the city’s architectural heritage back; every single delay affected the city’s economy.

The grand wooden staircase was brought back to its former glory

“That cost of money stuck in the project got me thinking. What we need in the city is a heritage committee that meets more often, that engages with heritage property owners on what more needs to be done, that announces meetings transparently on its website, and that shares with the world what transpired in those meetings. And yes, much as this may make me unpopular, we need people on the committee who possess hands-on experience in restoring heritage properties.

“When we turned over the place on rent to a jewellery retailer, the first observation was ‘Haan, kintu why did you not transform this into an art gallery? Aar kicchu toh kortei paartay…’ What most people need to realise is that the core of any heritage restoration project needs to be sustainability. The property’s end use needs to pay for the building’s maintenance unless you make that a residence. We may have got some things wrong here and there but if there is anything that we have got right it is this — the mansion generates its own funds to address upkeep (peeling plaster, leaking roof, termite treatment, glass breakage, etc.). Rupiya ghar se nahi lag raha hain. It’s a big thing considering the size of the property.

Today, the restored mansion of Sir R N Mookerjee, which now houses a Kalyan Jewellers outlet, pays for its own upkeep

“I know people have this big question: ‘Why did we emblazon the word ‘Kalyan’ across the entire facade?’ I have a counter question. ‘What is better — a destroyed mansion because there was no one to invest in its turnaround or a restoration where we have the brand’s name on the facade?’ I have a second counter argument. The same people who criticise me on this count have no qualms seeing sponsor names on the chest, collar, sleeve and back of all the cricketers representing our country. Go and see other heritage properties in the city that have the name of Starbucks and other brands on their facades. Why does no one criticise them? Our neighbouring building has Tanishq emblazoned in a large typeface, but no one seems to be critical of that! When one goes abroad, the logo of Apple on a heritage building is considerably larger than our typeface. Why pick on us alone?

“Somewhere people have forgotten what we have given back to the city. Maybe because we have kept a low profile. But just remember, this is the very city where a lovely old Kenilworth Hotel that could have been restored had to make way for The 42; where the palace of the Maharaja of Darbhanga — baap of all palaces in the city that could have made Tripura House feel like a child — was destroyed. These could have been saved if the owners had been given additional FAR that they could have sold, and that money used to restore the heritage property. It is all so simple and if the government introduces this, so many more properties can be saved and when that happens, the spirit of this wonderful city can be protected for decades to come.

‘We need to restore heritage properties and reuse them so that even as their end uses may change, their existence will not,’ says Aditya Poddar

“I will end with something that may sound corny to most people. These heritage properties are not khandahar (ruins); they represent our future. We will one day go, but they will stay. I see my forefathers in these buildings. They are not brick and mortar; they live. And if we look at them through this prism, we will need to stop saying ‘Let us not touch them because they are heritage!’ On the contrary, we will need to touch them, restore them and reuse them so that even as their end uses may change, their existence will not!”

I left Aditya Poddar with a suggestion to allocate some wall space inside the 17,000 sq ft property to the man who built his mansion. Then all his facade ‘sins’ would be forgiven. He didn’t immediately count his notional rent loss. Which means he might even say yes.