‘Manishbabu, would you be interested in…’ This phone call kick-started Kolkata’s largest private residential heritage property transformation at 48B, Muktaram Babu Street.

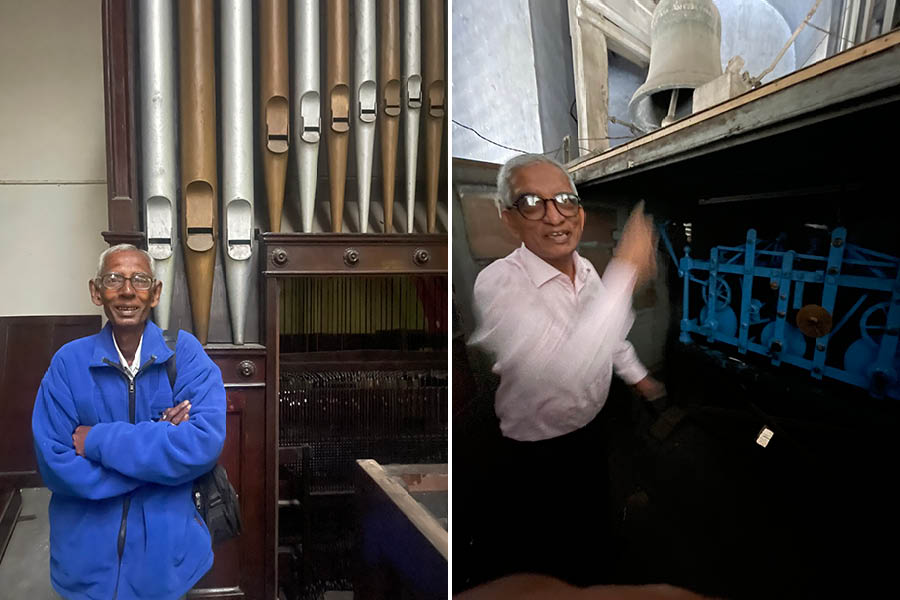

Manish Chakraborti recalled walking into the premises on Muktaram Babu Street beside Marble Palace. After visiting the architectural big brother next door (‘Etao dekhe ashi’). Manish would take his rounded spectacles off and in a pucca angrez orientation, hiss ‘Preposterous.’

This is why. There would have been a time when the zamindar of the property would have had his phaeton stand in isolated splendour waiting for savari; now, every neighbourhood resident parked his car in that courtyard on rent. There was a time when the owner of this place would have his horse, attendant and carriage stand there in attention awaiting the malik’s stepping out; now, neighbourhood cars reverse-gear into place any time of the night. Time-time ki baat.

A phone call kick-started Kolkata’s largest private residential heritage property transformation

Back to the telephone call. Manish heard a few words, stood erect, his breathing accelerated and then interrupted with ‘Ekkhuni aaschi’. He was off to meet Sushil Goenka at Emami.

This is what Sushilbabu told him: “This is where Emami started business in the early Seventies. Restore the property that explains in some ways the evolution of our business from Rs 3,500 to Rs 35,000 cr. Restore the property to what it was. Retrofit it partly around contemporary needs. Don’t make it a museum. Make it a living space.”

Manish did a recce. The courtyard had been transformed into a micro-market of sheds under a tirpaal. A makeshift staircase had been constructed connecting the thakurdalan to the first floor. The temple (garbhagriha) precinct had been segregated from the thakurdalan with a collapsible gate and converted into a godown. Every single room within the property comprised a mezzanine floor to enhance space area. The front porch had collapsed. The pillars had lost their plaster.

A makeshift staircase had been constructed connecting the thakurdalan to the first floor

And yet, Manish did not miss the splendour in the decay. The property had been constructed around geometric integrity. Because the imposing pillars had lost their plaster, he could discern the use of cambered bricks. The construction layers explained the structural strength — wooden beams, wooden runners, two layers of tiles and lime concrete (150-200 mm). The wall thickness was 700mm before the plaster. The columns supporting the outside porch were Ionic; the columns on the ground and first level were different, the former with no fluting and the latter with fluting.

The restored staircase

This is what Manish probably journaled: ‘Not just any structure. Appears to have been a proud architectural offspring between the 1850s and 1910s. No wonder Calcutta was not just the City of Palaces, but also the second city of the Empire.’

The time had come to return the 1830s property to the grandeur the way its architect — possibly a sahib behind a draughting table at Mackintosh Burn — had visualised. The client’s brief became the pivot: not just revive, but repurpose; not convert, but contemporarise; not just showcase, but make usable.

The client’s brief was: not just revive, but repurpose; not convert, but contemporarise; not just showcase, but make usable

This intent was soon tested. A part of the porch roof collapsed; KMC was surprised when the Emami team sent a letter headlined ‘Permission to restore’ where most owners would have sought to build afresh. Manish and the client responded with initiatives that would be boring for most. Suffice it to say that by early 2020, 48B had been contemporarised for a social outcome with moderate permissible modern enhancements. There is now a feeling of grandness when one observes the pillars; there is a robustness about the structure that says, ‘Look at me; you can’t ignore me’. The property, largely repurposed around a temple, is likely to last another 200 years before the next round of structural repairs become necessary.

The objective of this column is not to document the restoration in architect speak (imagine using the word ‘trabiated’). The objective is to reimagine Mullickbari as an architectural product of a golden period of Calcutta’s history and appreciate why serious corporate money was necessary to evoke the spirit of a city that was.

The columns supporting the outside porch were Ionic

The period from 1800s to 1850s — when Mallickbari was designed and constructed — was a fascinating time in the history of Calcutta. The formal history of the city was less than 150 years old. Raja Rammohan Roy lived on APC Road and probably intoned Farsi in his leisure evening courtyard circumambulations. Rajendra Mallik built one of the largest estates with 126 marble varieties. Hindu College had been established to educate Indian children. Dwarkanath Tagore was setting up large commercial enterprises. Viceroy House was the grandest private residence in Asia. Writers’ Building was the seat of the East India Company. William Carey was building an institution engaged in the research of new agricultural species and indigenous variants that would transform sub-continental cuisine. Keshab Chandra Sen was still a student forging concepts that would go on to create the Brahmo Samaj. Michael Madhusudan Dutt was jousting with conservatives when not writing poetry. Derozio’s cult following at Hindu College was attracting the regret of parents. Rani Rashmoni was building her trading empire and temples. Thomas Macaulay had introduced English as the medium of education that was to transform the country. James Prinsep was working on codes that concealed the secret of the Kharoshthi and Brahmi scripts. Teenager Ramakrishna Paramahansa was engaging with mystics with scarcely a clue of how he would go on to influence Indian spirituality. Bankim Chandra was a student. Vivekananda had not yet been born. And much of all this was transpiring within a 3-km radius of Muktaram Babu Street.

The construction layers explained the structural strength — wooden beams, wooden runners, two layers of tiles and lime concrete

If you go to the restored building at Muktaram Babu Street and see only the polished checkered tiles, you might miss the whispers of history. “It was from here that the pulse of the Bengal Renaissance began to beat over a hundred years ago. The lofty idealism, profusion of ideas and flights of fancy seemed mirrored in the architecture, spacious marble halls and sweeping staircases, ornate facades and aspiring turrets,” wrote Jug Suraiya. “In the baithak-khanas of the wealthy patrons of arts and letters, newly-discovered talent sparkled with greater brilliance than even the crystal chandeliers. All-night jalsas, or music conferences, featured ustads from as far afield as Lucknow and Benaras. Broughams and palkis rattled and swayed over the cobbled, gas-lit streets bringing the guests to the great houses. New currents in nationalist politics, poetry, education and social emancipation surged within the narrow lanes, seeking outlets for expression. The rich baboos with their pomaded hairstyles, elegantly pleated dhotis, flowing silken chaddors and debonair walking sticks were dilettantes par excellence. They patronised anything and everything from the 'pot' painters of Kalighat to the image-makers of Kumartolli, from imitation European objets d'art to the famous sweetmeat makers of the city who confected such delicacies as the rossogolla, the pantua and the Lady Canning, so called because Lord Canning's wife was said to be partial to them.”

The property, largely repurposed around a temple, is likely to last another 200 years before the next round of structural repairs become necessary

Swarup Chandra Mullick acquired 36 cottahs on 48 Muktaram Babu Street. His ancestors hailed from Rajasthan; the family business comprised trading in gold and silver (‘swarnabanik’); the surplus was invested in land and there came a time when this part of the Mullick family owned substantial properties in Calcutta (described family members as ‘khaal-er ei paar’, one of which was, according to family lore, Calcutta Medical College).

These Mullicks were also referred to as Singhabaahini Mullicks; they had been given the title of ‘Mullick’ by Akbar in the 16th century. These Mullicks established themselves in Muktaram Babu Street, which must have been at the heart of Black Town in the first half of the nineteenth century. Rajendralal Mallik followed a few years later and could even have been inspired by the property next door to create a grander structure that Mick Jagger considered important to visit early this year.

The Mullick descendants at 48B, who sold out in 2016, grew up on stories of a fountain in the middle of the thakurdalan and one in front of the mansion; one was removed because it interfered with the stocking of finished manufactured material; the other was removed because it had fallen into disuse.

The Mullick descendants at 48B grew up on stories of a fountain in the middle of the thakurdalan

Descendants feed on nostalgia. Of the resonant sitar in the ground floor music room. Of Ustad Vilayat Khan cross-pegged on the floor immersed in his instrument. Of ancestor Neelkanthbabu (well past his time) still being an opinion maker on which candidate should stand in the local elections and how ‘the para virtually ran on our writ’. The one line of regret: ‘Amader dubiye deoa hoyechhey aar aamra chhartay baddhyo hoyechhi’.

Nostalgia is the red herring of this column. The focus is something else. If more corporates raise their game to archive and restore where they came from, a new dimension of the city’s heritage could emerge. I can name two right away: the need to present (not restore) the Birla gaddi in Kali Godam in a more formal way to a heritage-respecting audience so that we get a flavour of where old man GD babu built his empire while trading on jute; or archiving the room or desk in Tobacco House (BBD Bagh) where started a company that evolved into ITC Limited.

There are fables everywhere in Calcutta; what we need are storytellers.