The great socio-cultural divide between the two Bengals is not confined to common battlegrounds like culinary skills of the Bangals versus the Ghotis, or comparing the football heritage of Mohan Bagan and East Bengal. It does not even end at intellectual fighting over Ghoti heroes like Uttam-Soumitra and Bangal actresses like Suchitra, Sabitri and Supriya.

This divide was once wide for the Durga idol-makers of Kumartuli, where the rivalry and distinction between the two schools of sculptors were not only visible, but also a matter of open debate for years.

In the early 18th century, Kolkata’s Kumartuli area became the place where potters and clay modelers from Saptagram and Nadia started migrating to. Apart from pottery and doll-making, they started moulding idols too.

The lane where some of the world's finest idol-makers still live and work Somen Sengupta

When performing Durga Puja became a status symbol for prosperous families of Kolkata during the rule of East India Company, the demand of Durga idols also rose. In that early era, Jinu Pal, Kangali Pal and Ananda Pal, among others, all from Nadia, emerged as top idol-makers.

These sculptors followed two styles — ‘Kangshanarayani’ and ‘Bishnupuri’.

Both these styles had a common earthen platform on which Durga and her family were placed — all in the same line but of different heights and sizes. This form was decorated with various background chalas named Brindavani chala, Kailashi chala, Indrani chala and Brahmani chala.

In a nutshell, Bengal was at its creative best while making the idol ensemble on one platform — Ekchala. Soon, a new generation of idol-makers and stalwarts like Niranjan Pal and Jatindranath Pal emerged and became a household name among Kolkata’s royal families. Affluent business families and zamindars like the Debs of Sovabazar, Sabarna Roy Chowdhurys of Barisha, Mitras of Darjipara and Duttas of Hatkhola, among others, adopted this style of idol.

What was so distinctive about these idols?

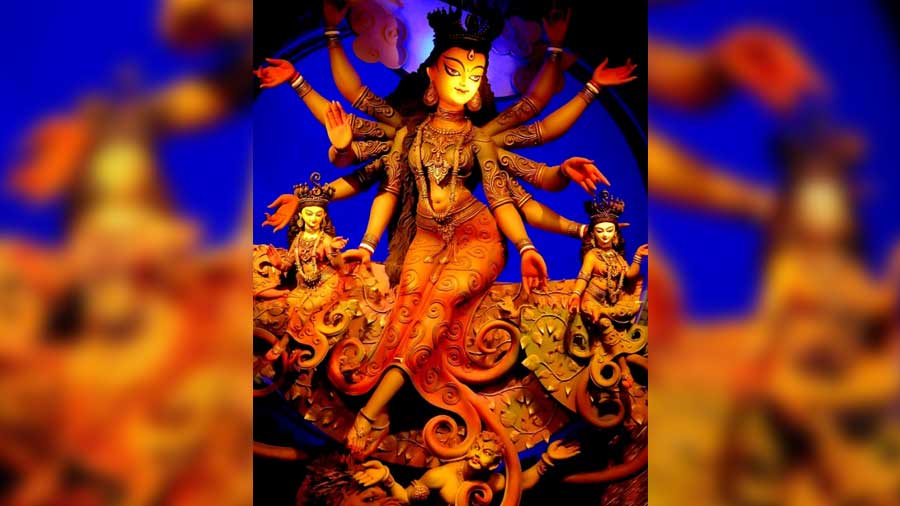

The old-school look of the deity — with bright yellow skin and bloodshot eyes Somen Sengupta

It was the otherworldly representation of the Goddess. The idol of this school has broad eyes — much bigger than a regular human being’s — and eight of her 10 hands are smaller in proportion. Though she looks human, the figure has larger-than-life features — overshadowing everything in her presence.

The skin colour of Durga and Lakshmi are painted deep yellow, while Mahishasura is painted green. The face of Durga is bigger than that of the other idols and her lion looks more like a horse or a half dragon. She is meant to look more divine and distinctive than her devotees. In this form, she looks more like a goddess than a daughter or mother — the form in which she is viewed in Bengal.

Idol-makers of this school were of the opinion that it is necessary to give the idol ‘supernatural’ aesthetics to generate devotion and fear in devotees. They thought a distance between man and God was inevitable — or else the tenets of submission and sacrifice would not be realised.

A Bagbazar Sarbojonin idol

The best example of this style can still be seen in the Bagbazar Sarbojonin idol, which was made in that form many years ago by Jiten Pal. It is still a signature idol to showcase this school of idol-making.

A revolutionary change in design

This picture changed almost overnight in the late 1930s when a young artist named Gopeshwar Pal brought about a revolution by breaking the foundation of the Ekchala into five and placing one idol on each of them.

Gopeshwar was an award-winning clay modeler from Krishnanagar, who won a gold medal in the 1924 British Empire Exhibition and toured various museums of Europe as a student of sculpture. There, he observed the realistic forms of human figures in stone sculptures. He gained a strong sense of realism and applied it to Durga idols after returning to home. His breaking of the Ekchala to panch chala is now considered a pivotal moment in idol-sculpturing in Bengal.

Gopeshwar also changed the common forms of the animals in the Durga family. His keen observation of animals at Alipore zoo helped him to make them more realistic.

Gopeshwar Pal brought realism to the idols Pal family

However, he was never a just a Durga idol-maker like the other Pals of Kumartuli. He showed little subsequent interest in idol-making and concentrated on the art of sculptures and went on to become a legend in the medium.

A change of guard

The art history of Kumartuli started changing from the early 1940s when communal tension across the Padma forced a large group of clay modelers to migrate to Kolkata, leaving everything behind. With them came a school of thought completely new to this part of Bengal.

These Hindu clay modelers from Dhaka, Bikrampur, Barishal and Faridpur had a very different idea of idol-making from those who were still dominating in Kumartuli for almost two centuries.

Dhananjay Rudra Pal came from Faridpur in 1947, followed by Rakhal Pal from Dhaka, Bikrampur, with 16 more families. His four brothers — Har Ballab, Gobinda, Nepal and Mohanbashi — soon migrated to Kumartuli by the end of the 1940s.

Ramesh Pal came from Faridpur and after Gopeshwar Pal, he brought unimaginable changes to idol-making. Along with him, a group of talented artists from the east started making significant changes to the traditional style of idol-making.

The first thing they did was to reduce the distance between God and man. They rejected the idea that for the sake of piety, the idol needed to look fearful with big eyes, a big face and bright yellow skin. They started making idols mirroring the human figure.

A typical 'ekchala' design Somen Sengupta

From nose and eyes to hands and breasts, all features were balanced to make the idol more human-like. With this, the fearful Devi became a daughter and a mother, and won worshippers’ hearts in Bengal. Thus, the school of East Bengal modelling was cemented in Kumartuli.

Not an easy transition

The huge influx of new sculptors from East Bengal were a big challenge for those doing business in Kumartuli for ages. From non-cooperation to physical abuse, there were all kinds of resistance to the exodus. The situation became more complicated when the new entrants started selling idols at cheaper rates to clubs and community pujas — a newly emerging market in Bengal.

But the situation also helped East Bengal sculptors as community pujas started booming in the city and suburbs after The Great Calcutta Killings in 1946.

Narayan Chandra Rudra Pal, the son of Rakhal Pal, said aristocratic families never used to take idols from East Bengali sculptors. But after Partition, their extravagances were curtailed and at the same time, the appeal of community pujas was on the rise. This made the job easier for refugee sculptors to enter a virgin market that was barely there before Partition.

They initially got land in Kumartuli, which was owned by the Roy family of Bhagyakul. However, local sculptors did not like their entry and the bitterness increased when they found that the idols made by East Bengali sculptors were cheaper and in high demand.

“My father-in-law Ganesh Pal, son of Jatindranath Pal, went to Ramesh Pal to seek his advice on joining the Government Art College. Sadly, Ramesh Pal did not help. It was my father Rakhal Pal who first tried to make peace between the two schools of sculptors for the sake of survival and soon his efforts bore fruit,” said Narayan Pal.

A merging of paths

A modern idol Somen Sengupta

Through this and over the passing of time, the eastern and western school of Bengal idol-making started to merge. By the late 1960s, with Ramesh Pal in the lead, refugee sculptors from the east started occupying the top seats of various art studios of Kumartuli. Rakhal Pal became a cult figure for his outstanding conception of idols in Barabazar market, Bata Sarbojonin, Kidderpore clubs etc.

In the late 1970s, the distinct differences between the two styles of idol-making started disappearing and a blending of the forms became a common feature in Durga idols made in Kumartuli.

By the early 1980s, top sculptors like Mohan Banshi Rudra Pal, Nepal Pal, Gouranga Pal and Sanatan Pal, among others, all had a strong influence of the East Bengal school. Gopeshwar Pal’s pioneering method of splitting the chala was effortlessly mastered by these artists.

This blending took new shape when art school graduates like Alok Sen entered idol-making. Sen changed the concept of Durga idols with realistic elements he saw around him. After him, Sanatan Dinda and Bhabotosh Sutar’s extraordinary style of blending the traditional and the contemporary has moulded the art of idol-making in Kumartuli — but not for the last time.

Somen Sengupta is passionate about heritage and travelling and has been writing about it for 26 years. When he is not executing duties as a senior executive in an MNC, he keeps an eye out for intriguing historical trivia and unearths forgotten stories. This also makes him an avid quizzer.